Good Still Hunting: where Scottish tradition & Southern innovation meet

If you’ve followed us for a while, you know how much we dislike puns. They’re cheeky. They’re smarmy. They are, for lack of a better word, punny. Puns wore out their welcome long before Shakespeare, and then he went on a 37-play bender devoted almost entirely to their use. They are, for all intents and purposes, a comical anachronism. We hope everyone — most especially, our friends—comes to dislike puns as much as us.

If not for Billy Shakes, puns would likely be a thing of the past.

That’s why we use puns as often as possible. Not because we love them and lack the wit that would carry us into comical kingdoms far beyond the realm of the purse-lipped pun. But purely for the benefit of humankind: to induce others to tire of puns as much as we did the first time we heard one.

In fact, even once all our friends tire of puns and pledge to discontinue their use, we’ll remain steadfast to our noble quest by continuing to use puns until anyone within a fortnight can’t stand to hear even one more. Because at that point, with no lame jokes left, they'll be able to concentrate fully on the great whiskey we've set out to make, an odyssey that started over six years ago and has finally culminated in our opening to the public.

In this installment of Crafted with Characters, which we’ve nobly entitled “Good Still Hunting”, we document our hunt for the perfect stills, the stills most suited to making the type of whiskey we want to make for years to come.

But first, a little background on the main types of stills available to whiskey-makers today.

Pot Stills

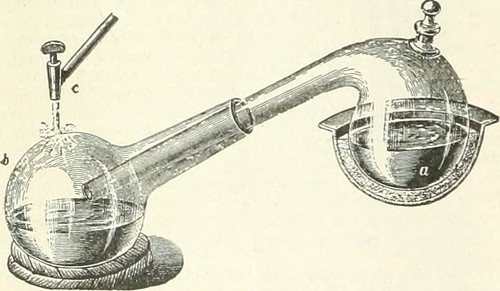

Pot stills are like Plato to the Socrates of the alembic still (which Miriam the Prophetess is said to have invented in the Middle East around the 2nd century A.D.). Whereas early alchemists used alembics chiefly for distilling non-consumables like rose water and perfume, pot stills were perfected for making whiskey.

An old pharmaceutical alembic, the Socrates of distilling systems.

Invented long before the printing press gave the thousands of novels that James Michener wrote each year a more widespread audience than the local cobbler, pot stills remain the chosen tool of the trade for single malt whiskey producers the world over: from Scotland to Canada to Japan to Australia.

But they're not chosen because they're easy. In fact, there's not any automation on traditional pot stills to speak of - they're operated entirely by manual levers, valves, and gauges.

Just as true sports car enthusiasts insist on a manual transmission, so too do many whisk(e)y makers insist on entirely manual pot stills.

If you're just getting into whiskey, an important distinction to know is this: single malt whiskies can generally only come from pot stills; blended whiskies and bourbons can come from either type of still, although often — especially in the case of the larger bourbon-makers — come from column stills.

Over the years, the single-malt-loving Scottish and Irish refined the pot still to become a copper-hewn sculpture of art. Consisting of a copper kettle heated from below, a tapered cone through which whiskey vapors pass — known as the swan’s neck, and a tube leading to a condenser — referred to as the lyne arm, pot stills produced the first whisk(e)y the world ever tasted.

At the most basic level, whiskey is made by heating something similar to an un-hopped form of beer to concentrate the ethanol and some of the flavors in the beer into more potent form.

To accomplish this, a pot still has an opening at the top of a kettle through which concentrated ethanol vapors pass into a tube surrounded by cold water. When the whiskey vapor that boils from the kettle passes through the tube touching cold water, the temperature of the vapor drops quickly, re-condensing the whiskey vapor back into liquid. Similar principle as how your glass of adult lemonade beads up when it’s hot outside.

Inefficient by design, a pot still distillation typically raise a 6–8% alcohol distiller’s beer to around 25–30% alcohol, known as “low wines”, during a first run through the wash still. This run relies on science: ethanol and whiskey flavors — known as congeners — boil at a lower temperature than water. So you can boil off and condense much of the ethanol and whiskey flavors before the boiling point of water is ever reached.

To make whiskey on pot stills, then, requires a second run through a spirit still to further concentrate the alcohol from 25–30% low wines to 65–70% "high wines" (or pre-dilution whiskey). This second run is where the art of distillation occurs, because the distiller must monitor the vapors coming off the stills to determine where to make “cuts” between what to throw out, what to further refine by redistilling it, and what to keep as liquid gold ready for the primetime known as a barrel.(1)

Our 500 gallon wash still and 300 gallon spirit still, standing resolute.

All the while, the swan’s neck design of a pot still allows enough separation between the whiskey vapor traveling up it and the liquid in the kettles below to hold back most of the heavier (and oft-less desirable) fusel oils that form during the fermentation process.

Some pot stills also contain a helmet like the Sci Fi astronaut masks you see above our stills that provide reductions in pressure as the spirit travels up the still, thus holding back additional higher-boiling compounds.(2) (Note that none of the stills we observed in Scotland’s famous Islay region — referred to amongst the team as the Phenol Crescent — has these helmets.)

People in the industry refer to this whole pot still process as “batch distillation” because each distillation happens in — perhaps surprisingly — batches. The constraint then, is how big your first still is, because you can only heat that much distiller’s beer to begin turning it into whiskey.

Column Stills

In contrast, continuous column stills have no such “batch” constraint.

Invented in 1828 by Scotsman Robert Stein, and perfected by Irishman Aeneas Coffey in the late 1830s (maybe that’s why there’s a rivalry?), who closed his Dublin-based Dock Distillery to sell his new still full time, column stills provide a more efficient method of distillation. Because they run continuously with no constraint of an individual kettle’s size, you can continue feeding distiller’s beer in them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, pausing only to watch Jim Kelly come out of retirement and lose in the Super Bowl.

Whereas with pot stills, you pour in a set amount of mash, then heat it from below using an outside heating source, with column stills, you continuously pour in mash, then heat the mash from below with direct steam injection.

The injected steam heats the mash to its boiling point, carrying concentrated ethanol and flavors from the mash up to the next plate with it. Each plate in a column still further refines the distillate, with a whiskey distillery often sending the distillate into what is known as a doubler or a thumper.

This doubler or thumper operates similarly to a pot still, heating up the distillate to further refine it by removing some of the high-boiling compounds such as propanol and isobutanol.

In addition to the large bourbon distillers, efficiency-minded vodka-makers also use continuous column stills.

Why?

Because, instead of pulling off whiskey from these plates, they can allow the spirit to continue up a very tall column, further stripping out flavor at each plate until the vodka is the colorless, tasteless, and odorless liquid that U.S. regulations require.

Hybrid Stills

Hybrid stills use the same batch approach as pot stills, but with a plate column on top of the kettle, rather than the helmet, swan’s neck, and lyne arm you often find in a pot still. (There are exceptions.) Some distilleries using hybrid stills bypass the column portion when they want a spirit to take on attributes of a pot still distillate, and engage the column portion when they want the spirit to take on traits of a column still distillate.

A little about our stills

Continuing in the tradition of single malt Scotch distillers, we worked with Vendome Copper & Brass Works out of Louisville to design our own custom twin pot still system. Not surprisingly, these gleaming copper beauties produce robust, flavorful whiskey, just like you find in Scotland.

But we wanted these stills to have a character all their own. So in addition to the standard kettle of most single malt Scotch makers’ stills, we requested that Vendome add helmets atop both the wash and the spirit still. The same helmets that, as we saw earlier, help remove fusel oils during the distillation process.

We then combine this traditional Scottish-style distillation with Southern innovation, including grain-in distillation and the introduction of corn, rye, and new charred American oak into the equation.

The net result is a truly exceptional whiskey that, we believe, you won’t find anywhere else. (If your bias radar is starting to beep more rapidly, feel free to turn it off — it’s mis-firing.)

With respect to the innovation known as grain-in distillation, perhaps we should digress:

In 1800s Ireland and Scotland, distillers lived in a rather cool, damp climate. Perfect weather for sheep. And ducks. And barley.

While barley makes damn good beer and whisk(e)y, leaving the grains in during fermentation produces a veritable explosion of husks .

Apparently barley is the messy child of the grain world.(3)

So single malt Scotch producers undertake a process known as “lautering”, in which they filter out the grain solids before fermenting their non-alcoholic grain soup, or mash.

In the hot South, where European immigrants couldn’t grow barley worth salt, they turned to rye and corn. These grains are much tidier than barley when left in during the fermentation and distillation stages of production.

This is corn. Apparently, corn in the old days was gray.

“But won’t the grain solids scald the bottom of your copper kettle?” Great question you just hypothetically asked. The very non-hypothetical answer is: yes, but.

But what?

Well, we have an automatic stirring mechanism called an “agitator” that continually stirs the rye and corn we use in our production to prevent these grains from sticking and scalding our pot still. Similar to how you stir oatmeal when you cook it the 18th century way in a big pot.

So in essence, we create whiskies that combine the flavor from Scottish-style twin pot stills with the flavor that comes from Southern-style grain-in distillation. The result is pure deliciousness, a supernova of flavor - not to be confused with that most bossa nova of flavor, the whiskey daiquiri.

Last but certainly not least, we’d be remiss not to give credit to the unique condensers that each of our stills possess. (They’re like unique little snowflakes that cool down whiskey vapor into delicious whiskey liquid.)

Look closely at the above photo of our stills, and you’ll notice a copper tube above the brass bell jar on the left, and a pyrex tube with copper coils above the brass bell jar on the right.

The tube on the left is known as a “shotgun” or “tube-and-shell” condenser. Take a cross-section of the condenser, and you’ll see a number of tubes within the large copper tube, arrayed much like a Gatling gun. The whiskey vapor that travels off the left still passes through these tubes, indirectly coming into contact with cool water that we cycle through the big tube. This style of condenser is more efficient than the coiled copper “worm” condenser that distillers used in the early days of whisk(e)y-making. We figured it would be bad for business if we used the most inefficient method on *everything* we do at the distillery.

On the other hand, the spirit still condenser, to the right of the gold, bell jar-shaped spirit still, is one of only a handful in the country in which the dynamics are inverted. Whereas the cold water passes through the big copper tube on the left, in the right glass condenser, the cold water passes through the small copper U-lines. The whiskey vapor that passes from the lyne arm above the right still into the glass unit thus condenses before your very eyes.

We chose this style of condenser to provide whiskey enthusiasts with an immersive, multi-sensory experience during tours. What better way to accomplish this than to actually see the whiskey condensing?

Today’s day and age has seen whiskey demand skyrocket. Accompanying this surge in demand for the liquid itself has been a surge in demand for stills. Seeing this, we placed the order for our stills with Vendome long before we ever broke ground on our distillery.

Nearly two years in the making, the stills finally arrived in October 2015. Permitting took us into June 2016, when — at long last — we were finally able to turn them on and begin producing whiskey, and licitly at that. Stay tuned for more on the first production run. We’ve got a lot of great content lined up.

— — — — —

(1) What the distiller throws out is referred to as “foreshots”, what the distiller further refines are known as “heads” and “tails”, and what the distiller sends to a barrel is known as “hearts”.

(2) Owens, Bill, The Art of Distilling Whiskey, Moonshine, and Other Spirits, p. 29.

(3) Note that some craft booze-makers believe that leaving barley husks in during fermentation results in bitter tannins that would render whisk(e)y rather unpleasant to drink. We’ve conducted our own experiments and found that these tannins don’t carry over during distillation.