What makes American Spirit Whiskey clear anyways?

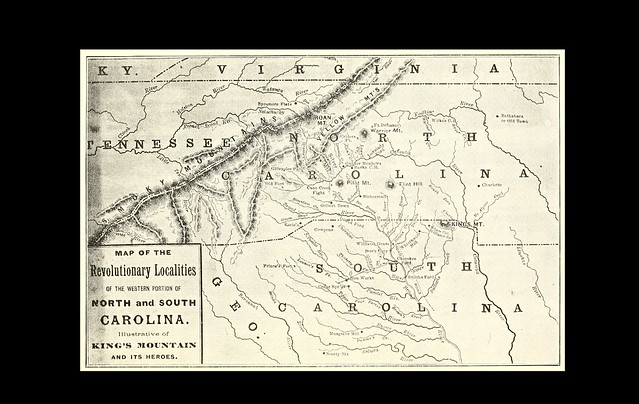

In the late 19th and early 20th century, a tinny-voiced man roughly the height of a chest of drawers dominated the moonshining scene of western North Carolina. Of Irish descent, his grandfather had fought in the Battle of King’s Mountain during the Revolution, a skirmish that President Theodore Roosevelt later described as the “turning point of the American Revolution”.

Out of necessity in the hardscrabble years leading up to the Civil War, Owens forewent formal schooling and, by age 14, had hired himself out as a “drawer of water and hewer of trees”. By the age of 23, his water-drawing skills had supplied him with enough money to buy 100 acres on Cherry Mountain, not far from Asheville, North Carolina.

Around that time, he transitioned from drawing water to distilling it, paying the justice of the peace who witnessed his marriage’s vows in brandy made from the cherry trees that grew abundantly on the slopes of Cherry Mountain. At its peak, the brandy-and-spice “cherry bounce” that Owens produced on his Cherry Mountain estate was served as far west as the Mississippi River.(1)

In Owen’s day —a period spanning from the era before Lincoln all the way through the first Ford motor vehicles — much of the spirits served were clear spirits. But the spirits enjoyed in his day and age were not the gin and vodka that came to dominate Prohibition and the post-War era. The spirits were whiskey and brandy, two spirituous elixirs normally associated with sepia tones.

Turns out that all spirits — whether gin, vodka, rum, or whiskey — leave a still as clear as a mountain creek or a conscience after bathing in one. It’s time in a barrel that gives most whiskey its brown hue — mainly from processes known as oxidation and extraction.

But if most whiskey is brown, why did we choose to roll out a clear whiskey as our first product? (Or “silver whiskey”, as some call it, similar to silver tequila.) As startups, craft distilleries have to concern themselves with cash flow, and often, the lack thereof. Socking away 100 barrels of bourbon for bottling in 4 years is all well and good, but in the meantime, you’ve got to figure out a way to keep the lights on.

That’s why so many craft distilleries of today bring a vodka or a gin to market first. Neither has to spend any time in a barrel, so a distillery can go from sacks of grain to filling glass bottles in less than a week. Compare that with the 12+ months needed to create a tasty bourbon — often much longer.

Not to mention, starting with vodka or gin means starting with a well-known category that doesn’t suffer from category-creation issues. So instead of having to educate thirsty drinkers on what exactly your product is, you can focus on what exactly differentiates your product from others on the market.

All of this adds up to a tried-and-true recipe for many startup distilleries, a wise move to ensure the lights stay on long enough to unveil the straight rye or sugarcane rum they’ve been aging all along.

We’ve always abided by the adage Do What you Love. You can truly tell the craft distillers who love gin from the care that goes into crafting their end-products. (St. George Botanivore, anyone?) At the same time, when we first created American Spirit Whiskey, we didn’t love vodka, or gin (we’ve since changed our minds on gin).

We did, however, love whiskey. We’d become well-acquainted with it since our days at the University of Georgia. We’d combed the City of Atlanta for our favorite bottles as they disappeared during the whiskey craze. We’d talked about the world at large while sipping it late into the evening.

So we decided that an unaged whiskey is where we’d devote our efforts. We knew the odds were against us — that we faced the category creation issues that have shut down concepts as wide-ranging as the Segway and the Sony MiniDisc. That we’d have to spend much of our days educating folks not just on what American Spirit Whiskey tasted like, but on how it was made, why you should try it, and, once a damn-that’s-good grin crossed their lips, what you could do with it. But adversity has never much deterred us, and so onward we marched.

And, as fortune favors the bold (or obstinate, as might be more applicable here), we are, almost six years later, on the verge of throwing open the doors to the distillery that will allow us to produce not only the spirit that got us here, American Spirit Whiskey, but many fine, aged spirits to come.

It hasn’t been easy. But we’re proud of sticking with clear whiskey when the sledding was tough - when we could have strayed from the path of doing what we love, but done so at the expense of feeling the true passion that comes with a calling. You might think of us as purists in the art form known as whiskey.

The art form began in the British Isles over 800 years ago, flowed west from the shores of Islay to the hills of the Appalachians, through the stills of that tinny-voiced moonshiner Amos Owens around the turn of the century, and, at long last, carved a course through the lives of all six of us at our distillery in the heart of Atlanta. We invite y’all to share the journey with us.

Buy our smooth-sipping silver whiskey online here.

----------

(1) Although we do not condone or associate with Owens' mindset - he served in the Confederacy during the Civil War - he is one of the most well-known moonshiners in American history and provides an example of the interest in grain-based clear spirits in times past. See Dabney, Joseph E., Mountain Spirits: A Chronicle of Corn Whiskey from King James' Ulster Plantation to America's Appalachians and the Moonshine Life, available here.