Whisk(e)y: Neat, with water, or on the rocks?

Imagine yourself cooking chili. You add meat and onions, then tomato. As a self-proclaimed Master Chili Chef, you naturally add salt to taste as the chili cooks. You sprinkle some salt into the pot, ladle a spoonful of the stew to taste, and decide it needs more salt. So you go to add a dash more salt and…the shaker’s top falls into the pot.

Salt cascades into the chili. Finally, you regain your wits and twist the salt shaker upright. But now, aside from this unfortunate scenario belying your claim to kitchen mastery, you’re faced with a conundrum: what to do with your overly salted chili?

This is too much salt for chili.

You consider throwing it out. But that would mean admitting to your spouse that you don’t actually know what you’re doing in the kitchen. So you decide to salvage it doing the only thing you know how: adding more ingredients.

To many starting their whisk(e)y journey, cask-strength expressions of 50%+ alcohol can trouble the palate like heavily-salted soup. (Of course, our Resident Salt Junkies, who will remain unnamed, might make the claim that soup can never be too salty.) One hundred twenty proof alcohol is just plain hot, the type of hot you find in south Georgia just shy of September.

Distillers know this, so absent the rare occasion of a cask strength release, they “proof down” or “cut” a spirit after pulling it out of casks (or barrels, depending on the size) to a less palate-eviscerating 80, 86, or 90 proof. This is the strength of the whisk(e)y when it joins fellow bottles in your home bar. [Note: we'll just use the term "whiskey" from here on out, as is the common usage in our jurisdiction.]

But now, just like with your chili, you must decide whether to add something to the whiskey to achieve tippling harmony - in this case, water.

As with many things in the lives of barristers, businessmen, and bourbon-makers, the answer is: It Depends. In this case, it depends on what your goal is.

With water

Adding a few drops of water to your whiskey breaks the surface tension that binds the whiskey molecules. The ensuing chemical reactions generate heat, which unlocks more aromas lying dormant in the whiskey. Spirits judges the world over proof down whiskies for this very reason — to fully evaluate a spirit’s varied aromas.

Some folks claim that you should proof down whiskey only with water from the distillery's own water source. However, this is not only impractical, but also a step that many world-renowned Scotch distilleries focused on achieving economies of scale(1) forgo in favor of diluting to bottle strength with water not from their distillery's local water source, but from Edinburgh or Glasgow.

So if you do decide to add water to experience the full gamut of sensory aspects a whiskey can provide, ignore this notion that only the distillery's water will do. and feel free add a few drops from any bottled or well-filtered water, preferably after tasting it neat.

Neat

Many whiskey enthusiasts, including at least one amongst our ranks, view the addition of water as roughly equivalent to rubbing Behr paint on a Rembrandt. The thinking here is that, without water, “you are tasting it in the natural form with all of the original distillery characteristics and flavors.” Source.

Behr paint would not augment this Rembrandt in acceptable fashion.

This first point is fair. But some take the argument a step further and claim that whatever proof a distillery bottles a spirit at is the proof it has determined as the strength at which you’ll best enjoy the spirit. While there may be some validity to this claim, in practice, a distillery may find that 48.4% is the ideal proof at which to enjoy a particular whiskey, but will instead bottle at a round number to simplify bottling.

So if you want to enjoy the whiskey in its original state, feel free to do so by drinking it neat; just avoid the claim that whatever proof the distillery bottles the spirit at is the singly perfect proof for the spirit.

On the rocks

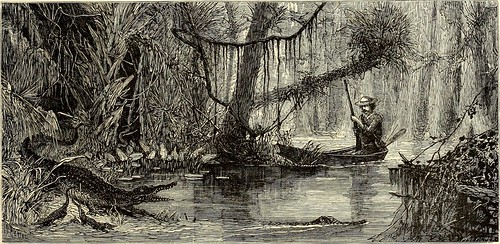

Some whiskey enthusiasts — especially ones who live in regions that some might describe as “subtropical” and others might describe as “swamp-like” — find their shirts coagulating with moisture during the summer months. In these tepid times, we’ll occasionally turn to the wonders of the nineteenth-century innovation known as “ice”, first harvested in 1806 by the enterprising New Englander, Frederic Tutor.

South Georgia today not so very different than this woodcut.

Although ice actually suppresses the aromas (or nose) of whiskey, when your A/C unit goes out during a heatwave and you find yourself laboring away over a pot of soup, there’s little more you can do.

So when you do find yourself looking to place ice in your whiskey to cool down during a heatwave, do so with large cubes like these that melt slower while still chilling your tipple.

Our approaches

All in all, we typically find that well-made spirits do reveal a different complexion once we add a few drops of water. So, when we’re really trying to evaluate spirits, we first inhale the whiskey aromas at bottle proof in a few, quick sniffs, let the spirit rest, then take deeper breaths. Once we’ve done this, we often add a drop or two of water to let the spirit open up and repeat the process. If the whiskey is still quite hot, we might undergo this process once or twice again.

But we always do so gradually. Because —similar to the case of chili, which requires proportionally more ingredients once you’ve skillfully over-salted it—if you add too much water to whiskey from the outset, you’re left with the very real dilemma of adding more whiskey to regain the dram’s harmony. Of course, this is only a problem when we’re evaluating spirits for consistency. When we’re evaluating spirits for clarity on the great mysteries of life, adding more whiskey to a glass is generally a solution.

— — — — —

(1) As the Birthplace of Economics, it makes sense that Scotland has given birth to distilleries that favor one of the linchpins of modern economics: economies of scale.

This is too much salt for a pot of chili.

This is too much salt for a pot of chili. Behr paint would not augment this Rembrandt in acceptable fashion.

Behr paint would not augment this Rembrandt in acceptable fashion. South Georgia today is not so very different than this woodcut.

South Georgia today is not so very different than this woodcut.