Why Scotch boomed while Irish whiskey wilted

You may be aware that our double pot still system hearkens back to the traditional Scottish and Irish whisk(e)y* stills, in large part to allow us to experiment with high malt mash bills (recipes). If all goes well, we’ll blaze new trails in whiskey profiles and expand whiskey drinkers’ perceptions along the way. At the same time, we’re firm believers in knowing full well the traditions and distillers to whom we’re indebted.

A view of our stills

One of the more interesting questions from the last century in whisk(e)y is why Scotch succeeded, while Irish whiskey — until recently — wilted. Namely, why did Scotland’s top export experience a whisky-driven boom throughout many years of the 20th century, while Ireland’s industry withered down to a paltry 4 distilleries in the 1960s?

The question becomes all the more perplexing when reading about the earliest history of whisk(e)y. All but the Scottish appear to agree that the Irish Gaels created the original uisge baugh, whose name was later shortened to “whisky” by the lexically laconic British.

When Aeneas Coffey perfected the column still centuries later in 1834, Scotch whisky makers made the switch in hopes of making whisky for less money. But the whiskies they began producing were of such poor quality that Irish distillers, who had continued using traditional, flavor-retaining pot stills, added an “e” to distinguish their superior product from the inferior “whisky” of Scotland.

Yet despite Irish whiskey’s auspicious beginnings, its serendipity soon sounded a swan song. In 1838, a Catholic priest by the name of Theobald Mathew — which, according to Irish pronunciation, almost certainly rhymed with “Ah-Choo!” — established the Teetotal Abstinence Society. Sixty years later, James Cullen founded Ireland’s Pioneer Total Abstinence Association. The legacy of these temperance movements continues to this day: 20% of Irish adults are teetotalers.

But the challenges had only just begun with 1838’s first temperance movement. Beginning in 1845 and spanning a grueling seven years, the Irish Potato Famine — or the “Great Famine” in Ireland — sent the island’s population plummeting by 20%. One million emigrated to foreign shores and one million perished from starvation and malnourishment. During this time, Ireland lost an estimated 70 distilleries. Still, global consumers regarded the 20 or so remaining distilleries’ whiskey as some of the finest spirits in the world.

The Great Famine kickstarted a chain of events that later proved fatal to most of these remaining distilleries: the Irish bid for independence.

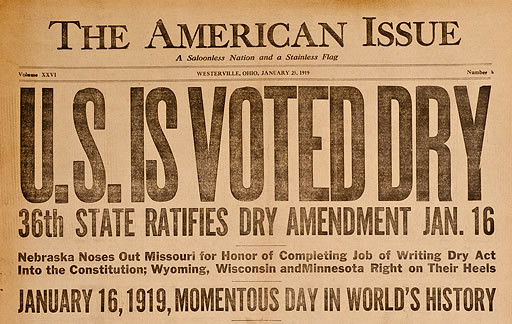

In the Easter Rising of 1916 and the successful Irish War of Independence that began three years later, Ireland attained complete independence from the crown. However, the victory came at the expense of British trade, costing Irish distillers their primary market. In a stroke of genuinely terrible luck, the U.S.’s thirteen-year social experiment (Prohibition) began during the height of the war with Britain, closing off yet another crucial market for Irish whiskey. By the 1930s, even the mighty Old Midleton Distillery produced less than three weeks per year.

World War II sounded the final death knell for Irish whiskey, which went the way that French cognac had only a few decades earlier during the Great French Wine Blight. Irish distilleries, which had scoffed at column stills since their inception, would never regain their footing against Scotch distilleries and their part-column-distilled blends. Today, blended Scotch still accounts for at least 90% of the global Scotch market.

In 1966, three of the handful of remaining Irish distilleries combined to form the Irish Distillers Association in a last-ditch effort to stay viable, a time when Scotch was experiencing a global boom.

Finally, in 1987, Ireland reversed the trend with the advent of Cooley, located on the east coast of Ireland in Dundalk. This marked the beginning of a slow turnaround for the spirit —in fact, last year Irish whiskey was the world’s fastest-growing whiskey segment. But this is more a testament to how far Irish whiskey had fallen than anything else, giving this delicious liquid significant room for growth without coming close to Scotch’s global sales.

A view from Galway, Ireland, one of the main stops on the way to the Connemara Peninsula. Photo courtesy of Jess Hunt-Ralston at Rose & Fig.

Certainly, the divergence between Scotch and Irish whiskey is not entirely due to the (bad) luck of the Irish or Scotch distilleries’ move towards blends. In fact, we’d be most remiss not to mention the friendly “open source” attitude towards whisky in Scotland, where distilleries are willing to trade casks of whisky to create new flavor profiles. This novel approach stands in stark contrast to virtually all major whisk(e)y markets around the world — from Japan to the Bluegrass State.

Scotch distillers’ willingness to trade is somewhat akin to Google and Facebook ascending to dominance by building open-source ecosystems to allow others to expand on their frameworks. In the case of Scotch distilleries, it’s more like “expand on flavor profiles”. It’s really quite brilliant and has led to incredibly tasty blends like Compass Box, in addition to the world-renowned Scotch single malts that win awards year-after-year.

That said, we may see more of this collaborative attitude in Ireland in the years to come, with smaller craft distilleries like Teeling and Dingle Distillery opening recently. (Craft distilleries, like their craft brewing forebears, seem to generally be open to collaboration.) Regardless, we’re excited to see what kind of a comeback the future has in store for Irish whiskey.

— — — —

*When referring to whisk(e)y as a broad category including both Scotch and Irish styles, we use the “(e)” nomenclature to be inclusive of both the Scottish and Irish spellings of the word.

A knockout blow for Irish whiskey

A knockout blow for Irish whiskey