CRAFTED WITH CHARACTERS

A collection of our thoughts on whiskey, spirits

&

the world

5 Whiskey Recipes That Will Blow Your Mind

The world of whiskey is an endless ocean of variation, taste and competition. Every year, craft distillers across the country make use of their creative talents and skill to create the best whiskey available on the market. They achieve this by using a variety of ingredients, mash recipes, distillation equipment, distilling methods, and barrel aging techniques. Each new batch is an art form as well as a science to create something truly splendid.

This guest post comes to us from Kyle Doran, of Mile Hi Distilling equipment.

The world of whiskey is an endless ocean of variation, taste and competition. Every year, craft distillers across the country make use of their creative talents and skill to create the best whiskey available on the market. They achieve this by using a variety of ingredients, mash recipes, distillation equipment, distilling methods, and barrel aging techniques. Each new batch is an art form as well as a science to create something truly splendid.

Celebrated cocktails take note of these exquisite whiskeys and aim to augment their flavor profiles within their recipes. Below, we've outlined a few delicious cocktail ideas, along with some of the most praiseworthy whiskeys available today. Let's dive in.

Resurgens Rye

Created by ASW Distillery (that's us!), Resurgens Rye has a very unique take on Rye whiskey. For the mash recipe, ASW uses 100% malted rye, including nearly 5% chocolate malted rye. They use malted rye (rather than the unmalted rye of most ryes on the market) in the mash. This allows for a more concentrated flavor profile of the rye itself to come through in the whiskey.

Resurgens Rye is distilled by a grain-in distillation technique, using Scottish-style double copper pot stills. The batches are then aged using an array of American white oak casks.

With hints of chocolate and sweet honey, Resurgens Rye is a perfect whiskey for making an Old Fashioned. Mix 1/2 teaspoon of sugar with a few dashes of water into a rocks glass. Add 3 dashes of Angostura Bitters. Muddle until dissolved. Add large ice cube to the glass. Pour 2 oz. of Resurgens Rye Whiskey. Stir and garnish with an orange slice.

Leopold Bros. Maryland-Style Rye Whiskey

Created by Leopold Bros. Distillery, Maryland-Style Rye Whiskey has a fruity and floral taste profile that is much less aggressive than other traditional American rye whiskeys. This is because they use a different type of rye and mash bill. In the 1800’s, two types of rye were primarily used to create mash for whiskeys. Pennsylvania Rye, and Maryland Rye.

The difference between these two ryes? Pennsylvania Rye has a nearly pure rye mash bill, which will produce a very dry and spicy whiskey. Maryland Rye, on the other hand, is made up with a 65% rye mash bill. It produces a much softer tasting whiskey with subtler spices and smoother flavors.

Leopold Bros. Maryland-Style Rye Whiskey's mash bill is around 65% rye, 15% corn, and 20% malted barley. The mash undergoes a bacterial fermentation in the distillery's cypress open fermenters. The acetic acid bacteria gives the mash its fruity flavors and aromas before the distillation phase. After distilling, it's then aged for 4 years in charred American oak barrels at 98 proof to produce an 86 proof end result.

For an alternative but delightful take on rye whiskey, give Leopold Bros. Maryland-Style Rye Whiskey a try. It's also great for making a Whiskey Smash. The light fruity hints of caramel and vanilla, mix well with mint leaves and lemon to create a refreshing cocktail. Place 5-7 mint leaves, a wedge of lemon and 1 tablespoon of sugar into a shaker. Muddle until the sugar has dissolved and the mint leaves and lemon are sufficiently ground. Pour 2 oz. of Leopold Bros. Maryland-Style Rye Whiskey. Shake, double-strain and pour into a rocks glass over 1 large ice cube.

Distillery 291's Single Barrel Colorado Rye Whiskey

Distillery 291's Single Barrel Colorado Rye Whiskey is a very notable whiskey this year. It was awarded the world's best Rye of 2018 by World Whiskies Awards. Its mash bill is composed of 61% malted rye and 39% corn resulting in a sweetness on the nose, spiciness on the palate and ending with a sweet finish. Finally, Single Barrel Colorado Rye Whiskey is aged for one year in American white oak barrels and then finished with charred aspen barrels. Michael Myers is the owner and head distiller at Distillery 291, which is located in Colorado Springs. His aim is to create whiskeys that reproduce the taste, smell and folklore of the Wild West.

With a flavor profile that includes cinnamon, oak and maple, the Vieux Carre is a great cocktail to create with Distillery 291's Colorado Rye Single Barrel Bourbon. Pour 3/4 oz. of bourbon, 3/4 oz. of Cognac, and 3/4 oz. of Vermouth into a mixing glass. Add 1 teaspoon of Bénédictine liqueur. Add 1 dash of each Peychaud’s Bitters and Angostura bitters. Fill mixing glass half full with ice. Stir until chilled and pour into chilled rocks glass.

Duality Double Malt

Another amazing spirit distilled by ASW Distillery, Duality Double Malt is the world's first whiskey of its kind because of its unique mash bill, distillation process and aging methods. The mash bill is made up of 50% cherry-smoked barley malt and 50% rye malt. Both of these malted grains are fermented together in the same vessel before the distilling process. The grains are left in during the first distillation which is done using the same Scottish tradition of double copper pot distilling that is used for Resurgens Rye. After distilling, the batch is aged in charred oak casks of varying sizes. As a result, this whiskey has a rich and complex flavor profile with hints of coffee, toffee, fruit and honey. Duality took home the Double Gold in the San Francisco World Spirits Competition in 2018. Whoever the connoisseur, this whiskey is definitely worth your time.

The Rusty Nail (Rusty Bob) is a simple, yet delicious cocktail that is perfect if you're in the mood for a sweet and light experience. With the rich tastes of honey, caramel, chocolate, coffee, and other mouthwatering flavors, the Duality Double Malt blends very well with the sweet herbal honey notes of Drambuie. Pour 1 1/2 oz. of Duality Double Malt and 1/2 oz. of Drambuie into a rocks glass over ice. That's it. Enjoy this easily made cocktail to your heart's delight.

Ridgemont Reserve 1792 Single Barrel

Ridgemont Reserve 1792 Single Barrel Bourbon is distilled by Barton 1792, a distillery established in 1879 and located in Bardstown, Kentucky. 1792 Bourbon Distillery gets its name from commemorating the year that Kentucky became a state. The mash bill is 75% corn, 15% rye, and 10% barley. Because of the mash bill ingredients and being aged 8 years in new charred oak barrels, this bourbon has subtle hints of butterscotch, maple and light oak. With the heat of the high rye composition, mixed with hints of caramel throughout, this is a whiskey worth appreciating. The Ridgemont Reserve 1792 Single Barrel has also won the Double Gold award in the San Francisco World Spirits Competition this year.

The sweet vanilla undertones of Ridgemont Reserve 1792, mixed with muddled mint leaves makes for a perfect Mint Julep. Place 6-8 mint leaves with 1 teaspoon of sugar in a rock glass. Lightly muddle until the mint leaves have broken down. Pour 2 oz. of Ridgemont Reserve 1792 over the mix. Add crushed ice until glass is topped. Garnish the glass with 1 mint leaf. Enjoy!

Generation after generation, distillers pass down the time honored tradition and artform of creating whiskey. As a result, craft whiskey distilleries are always looking to the horizon to expand on what their forefathers built before them. Amazing whiskeys are created every year by experimenting with different ingredients and techniques. Whether you're a newcomer or a seasoned connoisseur of whiskey, you will be able to appreciate each of these batches for a variety of reasons. Try out these whiskeys and cocktails and decide what you appreciate about the spectrum of different flavor profiles you find. We hope you've enjoyed this breakdown of some of the best whiskeys and cocktail recipes to try out this year.

Kyle Doran is a Colorado local and writer for Mile Hi Distilling, a manufacturer of high quality whiskey and moonshine stills as well as other distilling products. Kyle is fascinated by the history of craft distilling, the distilling process and loves to discuss different varieties of spirits and liquors. His favorite spirits are bourbon, whiskey and moonshine.

Interested in a tour & tasting at our Atlanta distillery? That's great news! Book your tasting & tour below:

Why Scotch boomed while Irish whiskey wilted

You may be aware that our double pot still system hearkens back to the traditional Scottish and Irish whisk(e)y* stills, in large part to allow us to experiment with high malt mash bills (recipes). If all goes well, we’ll blaze new trails in whiskey profiles and expand whiskey drinkers’ perceptions along the way. At the same time, we’re firm believers in knowing full well the traditions and distillers to whom we’re indebted.

One of the more interesting questions from the last century in whisk(e)y is why Scotch succeeded, while Irish whiskey — until recently — wilted. Namely, why did Scotland’s top export experience a whisky-driven boom throughout many years of the 20th century, while Ireland’s industry withered down to a paltry 4 distilleries in the 1960s?

You may be aware that our double pot still system hearkens back to the traditional Scottish and Irish whisk(e)y* stills, in large part to allow us to experiment with high malt mash bills (recipes). If all goes well, we’ll blaze new trails in whiskey profiles and expand whiskey drinkers’ perceptions along the way. At the same time, we’re firm believers in knowing full well the traditions and distillers to whom we’re indebted.

A view of our stills

One of the more interesting questions from the last century in whisk(e)y is why Scotch succeeded, while Irish whiskey — until recently — wilted. Namely, why did Scotland’s top export experience a whisky-driven boom throughout many years of the 20th century, while Ireland’s industry withered down to a paltry 4 distilleries in the 1960s?

The question becomes all the more perplexing when reading about the earliest history of whisk(e)y. All but the Scottish appear to agree that the Irish Gaels created the original uisge baugh, whose name was later shortened to “whisky” by the lexically laconic British.

When Aeneas Coffey perfected the column still centuries later in 1834, Scotch whisky makers made the switch in hopes of making whisky for less money. But the whiskies they began producing were of such poor quality that Irish distillers, who had continued using traditional, flavor-retaining pot stills, added an “e” to distinguish their superior product from the inferior “whisky” of Scotland.

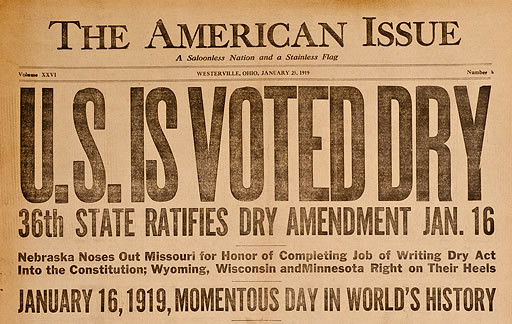

Yet despite Irish whiskey’s auspicious beginnings, its serendipity soon sounded a swan song. In 1838, a Catholic priest by the name of Theobald Mathew — which, according to Irish pronunciation, almost certainly rhymed with “Ah-Choo!” — established the Teetotal Abstinence Society. Sixty years later, James Cullen founded Ireland’s Pioneer Total Abstinence Association. The legacy of these temperance movements continues to this day: 20% of Irish adults are teetotalers.

But the challenges had only just begun with 1838’s first temperance movement. Beginning in 1845 and spanning a grueling seven years, the Irish Potato Famine — or the “Great Famine” in Ireland — sent the island’s population plummeting by 20%. One million emigrated to foreign shores and one million perished from starvation and malnourishment. During this time, Ireland lost an estimated 70 distilleries. Still, global consumers regarded the 20 or so remaining distilleries’ whiskey as some of the finest spirits in the world.

The Great Famine kickstarted a chain of events that later proved fatal to most of these remaining distilleries: the Irish bid for independence.

In the Easter Rising of 1916 and the successful Irish War of Independence that began three years later, Ireland attained complete independence from the crown. However, the victory came at the expense of British trade, costing Irish distillers their primary market. In a stroke of genuinely terrible luck, the U.S.’s thirteen-year social experiment (Prohibition) began during the height of the war with Britain, closing off yet another crucial market for Irish whiskey. By the 1930s, even the mighty Old Midleton Distillery produced less than three weeks per year.

World War II sounded the final death knell for Irish whiskey, which went the way that French cognac had only a few decades earlier during the Great French Wine Blight. Irish distilleries, which had scoffed at column stills since their inception, would never regain their footing against Scotch distilleries and their part-column-distilled blends. Today, blended Scotch still accounts for at least 90% of the global Scotch market.

In 1966, three of the handful of remaining Irish distilleries combined to form the Irish Distillers Association in a last-ditch effort to stay viable, a time when Scotch was experiencing a global boom.

Finally, in 1987, Ireland reversed the trend with the advent of Cooley, located on the east coast of Ireland in Dundalk. This marked the beginning of a slow turnaround for the spirit —in fact, last year Irish whiskey was the world’s fastest-growing whiskey segment. But this is more a testament to how far Irish whiskey had fallen than anything else, giving this delicious liquid significant room for growth without coming close to Scotch’s global sales.

A view from Galway, Ireland, one of the main stops on the way to the Connemara Peninsula. Photo courtesy of Jess Hunt-Ralston at Rose & Fig.

Certainly, the divergence between Scotch and Irish whiskey is not entirely due to the (bad) luck of the Irish or Scotch distilleries’ move towards blends. In fact, we’d be most remiss not to mention the friendly “open source” attitude towards whisky in Scotland, where distilleries are willing to trade casks of whisky to create new flavor profiles. This novel approach stands in stark contrast to virtually all major whisk(e)y markets around the world — from Japan to the Bluegrass State.

Scotch distillers’ willingness to trade is somewhat akin to Google and Facebook ascending to dominance by building open-source ecosystems to allow others to expand on their frameworks. In the case of Scotch distilleries, it’s more like “expand on flavor profiles”. It’s really quite brilliant and has led to incredibly tasty blends like Compass Box, in addition to the world-renowned Scotch single malts that win awards year-after-year.

That said, we may see more of this collaborative attitude in Ireland in the years to come, with smaller craft distilleries like Teeling and Dingle Distillery opening recently. (Craft distilleries, like their craft brewing forebears, seem to generally be open to collaboration.) Regardless, we’re excited to see what kind of a comeback the future has in store for Irish whiskey.

— — — —

*When referring to whisk(e)y as a broad category including both Scotch and Irish styles, we use the “(e)” nomenclature to be inclusive of both the Scottish and Irish spellings of the word.

Is rum the next bourbon? Our thoughts

Before bourbon became bourbon in the 1820s, before the American Revolution began, even before George Washington got his wooden teeth, rum was America’s favorite spirit. (Come to think of it, could rum’s high sugar content have played a part in GW’s wooden grill? He was a fan of Barbados rum, after all.) Given that our stills can, by design, only make whiskey, brandy, and rum, we thought we'd give our thoughts on whether rum is the next bourbon, a question that we've gotten quite a lot recently.

Before bourbon became bourbon in the 1820s, before the American Revolution began, even before George Washington got his wooden teeth, rum was America’s favorite spirit. (Come to think of it, could rum’s high sugar content have played a part in GW’s wooden grill? He was a fan of Barbados rum, after all.) Given that our stills can, by design, only make whiskey, brandy, and rum, we thought we'd weigh in on whether rum is the next bourbon, a question that we've gotten quite a lot recently.

Quality producers

Any spirit that's going to be touted as the next hot thing has to have a bedrock of quality producers - there's a reason moonshine has more or less petered out as a movement. So the first question we must answer in trying to unravel the market-based mystery of whether rum is the next bourbon is this: are there distilleries that produce flavorful, high-quality rum. The answer is a resounding yes. From the U.S.' only single-estate rum a couple hours south of us in Richland Rum, to true mountain rum in Crested Butte's Montanya, we're not staring at a dearth of quality producers.

As a related question, we must next ask whether rum's flavor profile is accessible enough for thirsty consumers across the country and the globe at large to enjoy it on a regular basis.

Rum’s flavor

The cocktail movement has led to a revival in all things rich in history, rum included. Craft cocktails are often sweet, as is bourbon, ice cream, and a number of other American favorites.

From this angle, then, it also seems rum could become the next hot spirit, especially when you consider how different rum flavor profiles can be: some smoky and almost Scotch-like, some unaged and spicy, like Bacardi or an unaged cachaca. Yet this could also hurt rum, as we'll explore a little later.

Whiskey's rise as a model?

Geographic provenance

We’ve seen Japanese whisky rise from relative obscurity to international stardom (and booming sales), bourbon rise from being a date-less prom-goer in the 90s to class president, and the resurgence of Irish whiskey. Thus, you could reasonably theorize the common thread being the centrality of a common geographic region. (Japanese whisky must come from Japan, bourbon must originate in the US, and so forth — lending a certain provenance to each liquid.)

Japanese whisky wasn’t event a thing until 1924, so it’s evidence that a region with a few quality distilleries can establish an entirely new category in a few decades. It’s conceivable to think a few quality rum distilleries in South Carolina or Spain or Sweden could do the same.

Cultural boost

Or you could reasonably assert that whisk(e)y — especially bourbon — has been bolstered by the craft cocktail movement and mixologists across the country embracing the spirit, which has led to a rise in restaurant & bar sales, ergo expanded bourbon sections, ergo more mindshare when people walk into off-premise establishments, ergo higher sales.

You might even say whisk(e)y in general has boomed because of pop culture support. Starting with high-class cocktails in Sex and the City, followed by Old Fashioneds in Mad Men, Jameson shout-outs by Lady Gaga, and untold whiskey references in popular songs all along the way.

The reality is, spirits of all types require a combination of factors to hit escape velocity.

Bourbon is booming right now, vodka had a real moment in the post-World War II years in America, Cognac did it one hundred years prior to that, and even gin did it in mid-1700s Britain (a period known as the “Gin Craze”). So rum might get to enjoy its moment, too.

Rum isn’t there yet and would need more institutional support. From what we’ve seen, barkeeps are starting to embrace rum for more spots on their cocktail menus precisely because it’s less expensive. So who knows — this could possibly be the first in a chain of events leading to the tipping point for rum.

Classic Cocktails

One last thing to mention in rum's favor: it doesn't hurt that some of the most iconic cocktails such as the Daiquiri and the Mojito happen to include rum.

Why rum may not quite become the next bourbon

We would be remiss not to include a few bullets about what may make rum less likely to take off than Japanese whisky, bourbon, and Irish whiskey and the booms they’re all enjoying:

- Currently, the majority of rum distilleries reside in tropical areas where aging occurs much more quickly because of the heat. So it’s very difficult to age a rum for 23 years, or even 5 years for that matter. (Up to 10% is lost per year to evaporation as "angel's share" in the hottest climates.) So if consumers look to age as a defining factor of quality, rum could well struggle. For a little more on why age alone isn’t a great proxy for quality, check out Chad’s analysis here. That said, one of the most lauded whiskies of recent memory, Amrut, comes from equally as hot India, and lacks the age statements that some consumers demand. So not everyone adheres to this imperfect heuristic to assess spirit quality, countering our point.

- The word rum doesn’t have quite the ring of the two-syllable whiskies, cognacs, bourbons, and vodkas of the world. Even Old Tom Gin rolls off the tongue in a sing-song sort of way. It sounds inane, but these things matter. Bourbon is just fun to say.

- Rum’s lack of regulations could impede its progress. Bottles of spirits cost more than six-packs of beer, so consumers are less prone to experiment with craft spirits than with craft beer. One or two bad experiences with pricey rums could be enough to turn people off. As mentioned, rum profiles are all over the place — some rums drink like Scotches, others drink like vodkas. In contrast, even if a drinker doesn’t like a particular bourbon, they will rarely be entirely thrown off by the liquid, since regulations require 51%+ corn and a host of other things. So they’re unlikely to write off the entire category because they drank something they weren’t expecting.

- Classic cocktails not as famous as bourbon's. Despite the classic cocktails mentioned above, rum's most notable cocktails don't seem to have received as much cultural cachet as bourbon's in the form of the Manhattan, the Old Fashioned, and the Mint Julep. A show may come along that touts the cool factor of, for example, the Planter's Punch, the way that Mad Men bolstered the Old Fashioned. But we haven't seen one yet.

Our final thoughts

Personally, we’re cheering for rum because (A) it’s delicious, (B) Georgia has a couple awesome rum distilleries already (Richland and IDC), and (C) our own twin copper pot stills can make whiskey, brandy, and rum, so we wouldn’t mind getting to learn how to make another spirit.

Whether rum becomes as big of a spirits category in the market is up for much debate. But then again, a spirit doesn't have to enjoy a $3 billion market share like bourbon to be enjoyable. Craft distilleries across the country have made rum for a long while and will continue to do so, because it's damn delicious and other people seem to think the same.

A deep dive on Islay and its peaty Scotch

The sunrise splintered the drapes of our room at the Bowmore House B&B just after 6am. The blue that you only find on rural drives and remote islands stretched taut across the horizon. The breeze came in bursts off the Atlantic, still laced with hints of ice on this early May day. My wife and I had finally made it to the crowning jewel of our much-delayed honeymoon: a three-day journey into the heart of Islay and its bounty of whisky bliss. Some biased observers might call it the best honeymoon ever. I fall firmly into this camp.

The sunrise splintered the drapes of our room at the Bowmore House B&B just after 6am. The blue that you only find on rural drives and remote islands stretched taut across the horizon. The breeze came in bursts off the Atlantic, still laced with hints of ice on this early May day. My wife and I had finally made it to the crowning jewel of our much-delayed honeymoon: a three-day journey into the heart of Islay and its bounty of whisky bliss. Some biased observers might call it the best honeymoon ever. I fall firmly into this camp.

As Israel was the fulcrum of the Fertile Crescent for agriculture 4,000 years ago, modern-day Islay is the Phenol Crescent for modern-day whisky. The vast majority of its distilleries produce some of the world’s peatiest Scotches, clocking in at 15–300 parts per million in phenols. (In contrast, The Macallan — what some would consider a moderately smoky Scotch — has 1.5 phenol parts per million.)

To venture into the depths of one of these distilleries is to walk through history — living, breathing halls that have produced some of the world’s best whisky for centuries. Even before I stepped off the ferry at Islay’s Port Ellen — itself a now-shuttered distillery of legend, bottles fetching thousands of dollars — I rated a number of Islay’s whiskies as many of my favorite drams of all time.

The more modern of the two ferries to Islay. Apparently, the other one has an impeccable track-record at inducing seasickness.

In homage to the annual Islay Festival of Music and Malt, which throws down in late May and early June every year (and runs through Saturday this year), we’ve put together a primer on each of Islay’s eight operating distilleries as of May 2016.

Although I’m not a distiller, I consider myself a whiskey-man, especially under the tutelage of our resident distillation encyclopedia and head distiller, Justin Manglitz. So many of my thoughts below relate to the art of distilling, in addition to the whisky and tasting room experiences you’ll find there and more general musings on Islay and its ineffable scenery. (Scenery that my uber-talented spouse, Jess Hunt-Ralston, photographed to perfection throughout this piece. Check her other work out at roseandfig.com.)

(And many thanks to our knowledgeable guide Stephen from Scottish Routes, who shared stories ranging from the Goliath-sized William Wallace to the escape artist wombats of Loch Lomond.)

Lagavulin ("log-uh-voo-lin")

One of the “Big 3” of Islay, Lagavulin’s pagoda-capped, white-washed warehouse announces itself from the shore as you ferry into Port Ellen. Affiliated with beverage multinational company Diageo, the distillery consistently produces drams that win gold medals the world over.

We arrived for the Lagavulin Warehouse Experience around 10am and followed the self-described “mound-shaped” tour guide Iain past the tastefully festooned, Lagavulin-green gift shop into the distillery’s cool, damp rickhouse. As we nestled in amongst thousands of repurposed bourbon barrels and rhinoceros-sized sherry butts, Iain got to work appointing volunteers to draw whisky directly from Lagavulin’s casks into a large beaker.

As we enjoyed the cask-strength (55%+ alcohol by volume) Jazzfest, 12-year sherry cask, 14 year, 18 year, 23 year, and 34 year, Iain poked fun at the lot of the 50 or so people attentively awaiting his next move. He reserved the comment “what, are ye writing a magazine article?” for me, pointing to the notebook I carry with me to jot down tasting notes. He selected numerous eager tipplers from the crowd to wield the copper valinch the size of a sword and withdraw a large beaker’s worth of whisky from each cask. (A valinch is known as a whiskey thief in the US.)

In between bouts of shaking the whisky — for aeration, one supposes, although some was leaking onto the floor — he asked us why we thought each cask loses approximately 3% of its whisky each year. One bold Dane suggested, “because you’re shaking it so much.” Iain grinned puckishly and told us that the 3% per year cut is the angel’s share, the environment’s price of admission through evaporation.

As we sniffed, sampled, and salivated our way through the briny, bittersweet whisky, I settled on the 12 year sherry cask finish and 18 year expressions as my favorites. In particular, the 18 year was white-gold, suggesting perhaps a third-use cask (the last use before being retired to some green thumb’s rose garden). The nose was somehow robust and delicate at once, a duality of dram evincing rose water, lilac, charred butter, green banana. The palate was even bolder, with pecan pie, dark chocolate, coffee, blackberry, bitter orange, saffron, sage, roast chicken with thyme, and something akin to honeyed porridge. (Not to be confused with honey-eyed porridge, which is the mythical dog of the Quaker Oats farmer.)

As we concluded the tasting, Iain suggested that a small group of us take photos on Lagavulin’s pier. With the sun bursting against the whitewashed wall of their warehouse and a band of enlivened Norwegians to each side, Iain grinned toothily and said, “Smile. Laphroaig!”

Those two words summed up the lively, instructive experience at Lagavulin. All in all, Lagavulin proved to be Jess’s favorite distillery experience on the island.

Soon, our tour bus whisked us off to the Kildalton Church for some much-needed sanctity and sobriety. An unattended Igloo ice chest with cakes, coffee, tea, and a donation basket greeted us like manna from the flawless heavens that are Islay's skies.

A few photos and some grave perusings later, we jostled down the road to Ardbeg for lunch and an early afternoon tasting.

Ardbeg ("ard-beg")

Ardbeg is, along with Laphroaig, Islay’s second-oldest distillery. But unlike its old kin Bowmore and Laphroaig, Ardbeg has not continuously operated since its 1815 founding (save for Bowmore's voluntary abeyance during the World Wars). At its peak, 200 people lived at Ardbeg, with the distillery at the town center. But the late 1970s & early 80s brought with them lean years in the whisky world, causing Ardbeg to shut its doors in 1981.

Fortunately, it later revived became associated with its next-dram-down neighbor Laphroaig before pairing with Glenmorangie. The group who owned Glenmorangie and Ardbeg later sold the distilleries as a package deal to Moet-Hennessy in 2005.

Ardbeg hasn’t changed much since its early days. They continue to produce some of the peatiest Scotches on the market, with their standard grain clocking in at 55 parts per million phenols. After pitching their dry distiller’s yeast (vs. the liquid yeast that Lagavulin uses), the mash spends 55 hours fermenting in washbacks of Douglas fir and Oregon pine. After this relatively short fermentation period, they pipe the 9% alcohol “distiller’s beer” to their wash stills - the only ones in Islay fitted with purifiers, which are metal tubes resembling old catalytic converters. The purifiers recirculate the heavier elements of the wash run back through the still before moving to the low wines tank. This allows them to inject cold water into tubes before the vapor reaches the wash still’s condenser, helping refine the spirit.(1)

Finally, the low wines travel through Ardbeg's spirits stills. Perhaps because of the purifying process during their wash run, they make a very quick foreshots cut (lasting only about 10 minutes) before sending the 72% alcohol by volume spirit into spirit tanks, ready for casks.

The resulting distillate reminds me a bit of peat-infused bourbon, with lots of cherry. Although pricey, the Corryvreckan is really well done. For those looking for something not quite as expensive, their Uigedail expression refers to one of their two water sources, and translates from Scottish Gaelic as “a dark, mysterious place”.

Laphroaig ("la-froig")

Bias alert: Laphroaig 10 has been one of my house whiskies for quite some time now. Not to mention, their 18 and 24 year expressions — quite difficult to find these days — rank among some of the most storied releases of all time. (Okay, maybe the 18 year isn’t that difficult to find.) So ending our first day here was like a child being permitted to visit Santa’s factory in rural China, er, the North Pole. We pulled into the parking lot of the last of the Port Ellen-side distilleries and stumbled with much coordination off the bus into that glimmering enemy of the besotted eyes, the unbridled Atlantic sun.

Knowing full well that we’d already been on in-depth tours of Ardbeg and Deanston in the Highlands, our guide at Laphroaig concentrated on showing us what differentiates their process. So off we went to the floor malting warehouse, where members of Laphroaig’s team rake damp barley back and forth across a floor until the barley germinates, releasing a number of enzymes vital to yeast during the fermentation process. Unlike Dante’s Inferno and Waiting for Godot, the back-and-forth motions yield not more misery and bewailed musings, but rather delicious malt, ready for moderate smoking from some of the peat Laphroaig harvests just around the bay from Port Ellen, near the Islay international airport’s lone runway. (They make approximately 20% of their malt in-house.)

A nugget of Laphroaig's peat.

After the entertaining tour, they led us to the warehouse for a quick peek at their casks before guiding us to the promised land, the tasting room. As Islay mandates that distilleries stop serving at 5pm, presumably so inebriated patrons can drive back to their hotels by the guiding light of dusk, my wife hustled to the Friends of Laphroaig kiosk. She returned with title — no doubt, in fee simple — to two 4-square-inch plots of land in a once-disputed field across the road from the distillery. Laphroaig may or may not have instituted the Friends of Laphroaig program as a response to the dispute.

We then sampled Laphroaig’s Three Wood and 15 Year expressions. Delicious, to say the least, my wife bought a bottle of the Three Wood to savor its coconut, orange marmalade, graham cracker, and chocolate notes upon returning stateside. I sprang for the 15 Year expression, as it doesn't grace the shelves of Atlanta's bottle shops. And, of course, we packed our 50ml bottles of Laphroaig 10 that we received in addition to our eminently buildable 4 square inch plots.

Bowmore ("buh-mohr")

Bowmore is Islay’s oldest distillery, dating to 1779 when a local by the name of John Simson opened its doors, before conveying it to the Mutters a few years later. (James Mutter was Vice Consul of the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, and Brazil through their Glasgow consulates.) In 1925, the German-descended Mutter family sold the distillery to J.B. Sheriff & Co. During World War II, Bowmore stopped production to accommodate the RAF Coast Command’s anti-submarine campaign headquarters.

Currently, Bowmore sources barley from both Islay and the mainland, and still conducts a portion of its own floor maltings. A former Bowmore warehouse encloses a public swimming pool heated by waste heat from the distillation process.

Alas, time did not prove accommodative during our visit — The Bowmore B&B where we stayed refers to the village rather than the distillery. I’ve always enjoyed Bowmore’s expressions (if you haven’t tasted their 18 Year, make haste to your nearest whisky bar) and regret not carving out the time the second morning we were there for a quick visit. But that would have required risking mental acuity for my favorite distillery, Bruichladdich. So I guess it means a return visit is in order.

Bruichladdich ("brook-laddy")

Long before I ever knew about Bruichladdich, when I was still studying for various degrees that I have since abandoned in favor of gainful employ in the world of whiskey, I dedicated my glass to gin. Of all the gins, Botanist had staked a claim to my palate more perpetual, more total than any little Laphroaig plot of land in fee simple for all posterity. These were the days when the bottle was the shape and size of a Bible, the gin’s 22 Islay botanicals residing demurely at the bottom of the label.

Occasionally, when I drink, I like to revisit the literature on the bottle whose contents I’m consuming. (I can assure you this is not a thing that happens when I drink alone.) One humid Saturday last June, both gin and tonic mysteriously appeared in my glass, and my old square bottle of Botanist in my hand. Naturally, I read the label and discovered, to my amazement, the same distillery that made my favorite price-accessible Scotch, Islay Barley, also made Botanist. So began an appreciation with the Bruichladdich Distillery that many unbiased observers might mislabel an “infatuation”.

Built in 1881 on the shores of western Islay’s Loch Lindall by the brothers Harvey, heirs to an Islay whisky dynasty, Bruichladdich met the same fate as Ardbeg in 1994, at the height of the El Dorado days of vodka. (If we were into puns, we might even jest the Road to El Dovodo. Fortunately, we’re not into puns.) In the late 90s, an avid cyclist and whisky enthusiast found the mothballed distillery during a rainy ride and put together a bid for the facility. For a number of years, White McKay rebuffed his advances until finally, at the turn of the new Millennium, they let go of their inactive asset for around 6.5 million pounds.

The cyclist, Mark Reynier, and master distiller, Jim McEwan, who’d worked his way up at Bowmore around the bay since the age of 15, pushed Scotch in all kinds of new and exciting directions. From focusing on the terroir of Islay through such releases as Botanist using 22 island botanicals, such as gorse, a thorny bush of yellow, coconut-scented flowers, to experimenting with finishes like red wine casks and the most aggressively peated Scotches in the world, Bruichladdich lived up to its motto: Progressive Hebridean Distillers. (In Scottish Gaelic, "Bruichladdich" means "rocky beach" or "purply beach".)

Twelve years later, Mr. Reynier and company sold Bruichladdich to Remy-Cointreau for a tidy 58 million pounds. For you math-literate and finance-geek types, that’s a return of over 66% per year in simple interest. The distillery now employs 72 people, a remarkable feat for a distillery that wasn’t even operational 16 years ago. Some time in the near future, they also plan to reintroduce the floor maltings that went by the wayside in the 60s. From my completely doe-eyed and myopic vantage, the quality has not suffered post-merger - the influx of funds has just meant a bigger budget to tell the world about their delicious whisky.

With a bigger budget comes the ability to afford bolder Pantone colors.

And the tour matches the quality. We enjoyed the morning stroll past vintage photos of their team, sampled the hefeweizen-esque distiller’s beer from their Oregon pine washbacks, and marveled at their legitimately ancient stills. In addition to their fairly standard-looking wash and spirit stills, they also showed us “Ugly Betty”, one of the last remaining Lomond stills, where all the world’s Botanist supplies are made in the span of only a couple of months every year.

The tour concludes in, where else, the tasting room, where you can buy rare extra-aged expressions, sample many more common expressions, and fill your own 500ml bottle from one of their two cask-strength Valinch series whiskies. These are one-off experiments only available at Bruichladdich that one drinker might describe as “utterly delicious”, while another, more hyperbolic sot might describe as “life-changing”. This go-round, my wife brought home the 10 year, heavily peated rioja finish Port Charlotte (yes, that Port Charlotte of lore).

Meanwhile, I opted for the 26 year, unpeated bourbon finish Classic Laddie. All in all, my favorite distillery experience on the island.

Kilchoman ("kil-who-men")

Islay’s newest distillery is also its smallest. While Islay is best-described as “rural”, Kilchoman is better-suited for the word “remote” — both miles from any town or other distillery and, unlike the equally-as-remote Bunnahabhain, stranded inland. To get there, our vehicle hunkered and jumped past rubber-necking sheep on the peat-cratered road.

The story goes that, after World War II, the family that owned the site on which Kilchoman resides were in the hunt for a vehicle that could navigate the island’s peaks and troughs better than cars of the day. After searching high and low, their search came up dry, so they took matters into their own hands, welding a cabin onto a sedan of sorts. The result was something that looked strikingly similar to the early Land Rover prototypes. Whether Land Rover lifted the idea from this Islay family is a matter of conjecture, but at the least, you can see how an Islay resident might conceive of the idea.

Like Lagavulin, Kilchoman has opted for the traditional pagoda-style turrets that maximize the air flow to the malt kilns. If Kilchoman bought all its malt from Diageo’s Port Ellen malthouse on the island, Kilchoman, which began in 2005, wouldn’t have needed such technology. But, true to its motto as “Islay’s Farm Distillery”, Kilchoman not only malts a large portion of its barley onsite, but also grows the same barley in the surrounding fields.

Its single 4000 liter wash still and correspondingly smaller spirit still make Kilchoman significantly smaller than many of the island’s distilleries. (By at least a factor of five if our math is correct.) But if you’ve ever had a dram of their flagship, Machir Bay (or "fertile landscape bay", in Gaelic), with the beautiful cornflower blue label, you know that what Kilchoman lacks in quantity, it more than makes up for in quality. Perhaps it has something to do with their ex-Buffalo Trace casks.

The tour guide was probably the most personable of any guide we met on the trip. (All the guides were entertaining in their own right.) At only eleven years old, Kilchoman’s stills are much newer than most stills on the island, and also contain the only reflux bubble I saw at any of the distilleries. (We at ASW Distillery have a similar reflux bubble here, 3rd photo.)

This can help provide more precise control over the final distillate. By applying lower heat for longer, the distiller can induce the spirit to condense on the sides of the relatively cooler reflux bubble and drop back into the kettle of the still more times before rising into the condenser. The result is a spirit that has undergone more “mini-distillations” before passing to the next stage of production.

Unlike the other tours, which ended after a look at the stills, Kilchoman led us to their bottling line to see us just how manual and hand-crafted their operation is.

Finally, they ushered us into their private tasting room for a tasting of Machir Bay, Loch Gorn, and 100% Islay. As delicious as the last two were, the Machir Bay still captivated me the most with its notes of coconut and pound cake. As an independent distillery farther along in their whisky journey, we hope y'all give them a look next time you're in the hunt for something new.

Caol Ila ("cool-eela")

Not far from Islay’s world-renowned and Hollywood-enamored Woollen Mill where two of the world’s six operational Spinning Jennys clank out garments day after day sits Islay’s largest distillery and smallest tasting room: Caol Ila. Perhaps best known for supplying a large portion of the whisky that tumbles into Johnnie Walker bottles, Caol Ila has a small but dedicated following.

One of the world's last functioning Spinning Jennys.

Our trip included two such loyalists, Norwegians who, while sipping whisky one damp Wednesday evening with members of their Dram Club back in Norway, had found Caol Ila 18 to qualify for their highest echelon of whiskies.

The narrow road to the distillery winds its way across Islay’s wind-swept fields before a final descent down a road perhaps better meant for pack mules than charter buses or Mercedes vans. Not a quarter mile across the Sound of Islay, a strait with one of the world’s strongest currents, the rocky mound of Jura rises like a breaching mastodon, beads of skittish deer dripping down its back.

This proved to be our shortest visit, as our guide Stephen had a promise to keep with the Bunnahabhain staff, who apparently prefer punctuality to the opposite. The tasting room barely fit our group of 16, but the staff was friendly as they poured us whisky. We sampled two drams, including Moch — both of which seemed a bit one-dimensional to my palate — before posing for a photo with our backs to Jura and the swift strait separating the two islands. As an interesting aside, in 2011, the government hoped to capitalize on the strait’s power by giving the green light for an innovative tidal turbine green-energy project on the ocean bottom.

For Caol Ila enthusiasts, this will be a welcome stop, although for the uninitiated who lacks that most precious resource, time, I would encourage forgoing it in favor of Bunnahabhain just a few minutes to the north.

Bunnahabhain ("boon-uh-hahvin")

The northernmost distillery on Islay, Bunnahabhain lies a few clicks north of Caol Ila. As you arrive, the slate gray tides slushing against polished ocean stones sounds like a distracted daydreamer sweeping a porch. Across the Sound stand the Paps of Jura, a somewhat oxymoronic name given to the two barren slopes prominent on that end of the island.

A fine distillery in its own right, Bunnahabhain is perhaps best known as the “unpeated Islay whisky”. Affiliated with the Deanston Distillery in the Highlands, their flagship 12 Year and delicious 18 Year both fall into this unpeated category, which you can sample up a flight of stairs, past a mounted bell formerly used to announce allotted-dram time.

Before heading to the gift shop, it’s worth checking out their version of the Distillery Experience, nestled in the back of an Amontilladan-like catacomb of their warehouse. The distillery braces you against the cold of the catacomb by furnishing complimentary blankets on the pews surrounding the selected casks on display. In lieu of a jaunt through the rest of the distillery, our tour guide brought us to this dunnage lounge straightaway and talked about the history of the distillery and its whisky.

Both effervescent and knowledgeable, our guide spoke to the distillery’s annual production (around 1.3 million liters per year) and its capacity (closer to 2 million liters per year). Apparently, the demand for Dewar’s, where the casks that don’t make the cut for Bunnahabhain’s own bottlings end up, is not what it once was. (Down 5% in 2015.)

After a sampling of a sherry-influenced expression straight from the sherry butt they had finished the whisky in, we walked back to the tasting room for our final organized tasting of the trip. The 12 Year was a solid expression, brown sugar and jam on the palate, while the 18 Year really shined, melting on the tongue like a warm salted caramel. Fitting, given Bunnahabhain’s location next to the ocean.

Before departing, our group pooled resources to buy Stephen, our wonderful tour guide, a bottle of Bunnahabhain Toiteach. As much as he’d spoken highly of Lagavulin, Laphroaig 18, and Bowmore, throughout the trip, he’d been raving the most about Bunnahabhain. We figured the least we could do would be to give him a bottle he wouldn’t be permitted to consume any time soon. (Duty calls, after all.) He graciously accepted the bottle and took it home to enjoy with his niece, no doubt.

What's next ("watts-neckst")

If you like the taste of Scotch, or enjoy spending time with those who do, Islay is a must-visit. Don't let its remote location deter you. It's only a half-day's drive from the international airport in Scotland's largest city, Glasgow - and half that time is spent on a truly inspirational ferry ride past rocky atolls and uninhabited islands. The weather in spring alternates between brilliant sunshine and hovering mists, but the temperature doesn't dip much below approximately 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Certainly not a place to soak up the rays on a beach, but pretty much the ultimate place to soak up the rays of the liquid sunshine in your glass. GO. And make haste. You aren't getting any younger.

(Fortunately, neither is the whisky. Unless you've become despondent about age statements disappearing from bottles. Which, historically, is quite precedented, as age statements only appeared with consistency fairly recently as companies figured out ways to market their stocks of long-aged whisky. But that's for another entry entirely. Until then, Cheers and Slainte!)

----------

(1) In the US, a purifier is known as a dephlegmator and is more often associated with the column stills used in large-scale bourbon distilleries, rather than the pot stills of small-batch makers. Current President of the American Distiller’s Institute, Bill Owens, in his book The Art of Distilling Whiskey, Moonshine, and Other Spirits, describes it thus: “The dephlegmator resides above the top bubble-cap tray. It is a chamber at the top of the column with numerous vertical tubes for the vapor to travel through on its way to the condenser. There is a water jacket around the vertical tubes that the operator can flood with cooling water to increase the amount of reflux [volume of spirit that recirculates through the still for further refinement]. The water level in the dephlegmator can be adjusted to give granular control over the amount of reflux.”

7 countries you’d never guess make great whiskey

Browse the whisk(e)y section of your local bottle shop and you’d be forgiven for thinking the juice is made in only one of five countries: Canada, Ireland, Japan, Scotland, and the US. Indeed, you’re hard-pressed to find any shop in Atlanta carrying anything from countries outside of the Big 5 (the Swig 5?). But grains just so happen grow elsewhere in the world, and wherever grain goes, liquid gold is sure to follow.

Browse the whisk(e)y section of your local bottle shop and you’d be forgiven for thinking the juice is made in only one of five countries: Canada, Ireland, Japan, Scotland, and the US. Indeed, you’re hard-pressed to find any shop in Atlanta carrying anything from countries outside of the Big 5 (perhaps the Swig 5?).

But grains just so happen grow elsewhere in the world, and wherever grain goes, liquid gold is sure to follow. So while you may not have ready access to whisk(e)y from the countries in our list, you can always seek them out through awesome online retailers like Masters of Malt or in duty-free shops at international airports. Or, you can visit the distilleries themselves if you find yourself in one of the countries. (That makes it sound like international travel is a sort of routing error on an afternoon hike, doesn't it?)

Czech Republic

Famous for ornate castles and excellent beer, you may not have known the Czech Republic also shares common ancestors with Ireland. Anthropologists have found that the Celtic people first appeared in the archaeological record in what is now the Czech Republic around 270 BC. (Around the same time the Celts showed up in the Land of Eire, too.)

Karlstejn Castle in the Czech countryside.

And, like the Irish descendants of the Celts, Czechs have taken their mastery of beer a step further, into the domain of uisge baugh.

Perhaps the most notable distillery in the Czech Republic is the Pradlo Distillery. (Another produces a 12 year-old single malt described by one reviewer as rather more like “an inexpensive blend than a 12-year-old single malt”.)

During the country’s Communist reign, the regime banned many foreign imports, including Scotch and Irish whiskies. The existing Pradlo Distillery thought it a safe bet to start producing whiskey in the pot stills that, until the 1970s, they had used mainly for plum brandy (slivovitz) and never for whiskey. After all, even Communist regimes have their elites, and even some of those elites are apparently partial to a fine dram.

The challenge was that laws prevented Pradlo’s distillers from visiting other countries’ whisk(e)y-making operations to study. So Pradlo taught itself by way of musty books and tastings of their own experiments.

You may be familiar with Scotland’s silver bullet in whisky-production, its peat bogs. But Scotland isn’t the only country with such swamps of compacted carbon. The plains of the Czech Republic have them, too. Only their peat apparently doesn’t play as nicely with whiskey, so they scrapped the plan in favor of importing peat from Scotland. (Why the regime permitted the importation of peat but not whisky remains a mystery.)

Their recipes perfected, they began to barrel the juice in casks of Czech oak in 1984, only to see Communism’s fall in 1989 bring down the distillery with it. Once again, delicious single malts from other countries were available, and Czech whisky was pushed to the backburner — really more like the back of Pradlo’s warehouses.

So Pradlo’s stocks of whiskey bided their time for nigh twenty years, until London’s Stock Spirits bought the plant and discovered the casks. They soon released bottlings of the whiskey under the name “Hammerhead” — an homage to the giant hammer mill on the premises.

We had the opportunity to taste the 1989 cask and found it to be rather delicious. Alas, our tasting notes eluded capture by the pen, so we are left to recall it was rather malty and lemony with baking spice, or perhaps even fennel, gracing the palate.

Many thanks to the Alcohol Professor for a well-researched article on the history of Pradlo to guide our writings here.

France

Just a 110 mph jaunt down the autobahn from the Czech Republic is a country of Gallic gourmands by the name of “France”. One of the more inspired producers of adult beverages in the world, France can legitimately claim some of the world’s best wine (Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne), brandy (Cognac, Armagnac), and fruit brandy (Calvados, pommeau). (Or “fruit spirit”, as the EU requires distillers to call fruit brandy).

But whiskey? Who knew.

Turns out, we did, beginning in 2015. Not to say French whiskey hasn’t been around much longer than our knowledge of it, but we were fortunate to taste both Brenne and Michel Couvreur towards the end of 2015. (The first at a World of Whiskies event in Atlanta; the second in our team’s shared Whisky Advent calendar from Master of Malt.)

Both brands have unique finishing methods, taking their cues from cognac. Brenne is perhaps the first single malt to experience a finishing rest in second-use cognac casks. Michel Couvreur, on the other hand, maintains two wildly different cellars for aging its stocks, one humid and damp, the other dry. (Similar to the chais, or aging warehouses, of cognac, some of which reside in relative dryness on the hills above the Charente River, and some of which reside in damp cellars adjacent to the Charente.)

The result with Michel Couvreur is totally different stocks for blending — the “dry-aged” stocks gaining alcohol by volume over the years to result in a spicy dram, and the “damp-aged” stocks losing alcohol by volume, resulting in a round, smooth spirit.

As a craft whiskey maker, we can’t help but appreciate the forward-thinking approaches to finishing whiskey these two companies have found and wish them much continued success!

A French chai.

India

Fact: India is the world’s top-consuming whiskey nation.

Fact: Much Indian whiskey is made from sugar, which, in our eyes (and the eyes of the EU and the US) disqualifies it from being whiskey, which must be made from grain.

Fact: Despite Fact 2, two of the world’s best single malt producers call India home: Amrut and Paul John. (The latter’s website includes photos of a bottle of Paul John, a shipwrecked boat, and a palm tree. It’s rumored that the shortlist of names for the distillery, in addition to “Paul John”, also included “Robinson Crusoe”, “Swiss Family Robinson”, and even “Ringo George”.)

One explanation for such delicious single malts is India’s tropical climate in Bangalore (where both of the distilleries reside). Hot as the dickens and humid enough to make your sweat cling for dear life to your skin.

In other whisk(e)y-producing countries, you find one of these two environments: Scotland is damp, Kentucky is hot. But India combines both to result in a truly unique dram.

Although we’ve never tried Amrut, we can attest to the quality of Paul John’s whiskey and hope to have a chance to try more of them in the future.

The longest single-river bridge in the world, in Patna, India.

New Zealand

Japan. It’s hot. But we're not talking temperature like India—rather, in terms of the whisky departing its casks for the green pastures known as our Research lounge. But Japan isn’t alone when it comes to Pacific islands with distilling traditions.

New Zealand, thousands of miles south of Japan, lays claim to the world’s southern-most distillery in the aptly named Southern Distilleries, Ltd., who seek to advance a whisky-making tradition around since before 1865, the year the government passed the Distillation Prohibition Act. (Spirits and senators have — since at least the Middle Ages — tangoed in a sort of two-steps-forward-one-step back kind of dance.)

As lore and legend agree, the Hokonui region of New Zealand’s south island had a particularly strong affinity for whisky. By the 1870s, Scotch and Australian whisky imports arriving on New Zealand’s docks were so watered-down “that a dram was often offered a chair as it didn’t have the strength to stand up.” (link) So Hokonui’s residents begged their local roughnecks to add moonshine to their repertoire.

Mary McRae, a Scottish import far stronger than the Scotches of the era, agreed to take up the thirsty Kiwis’ cause. Her pedigree was top notch- she had trained at a number of Scotch distilleries before arriving in New Zealand in 1872 — so her distillate was bound to be good. She and her sons began producing a range of moonshines, allegedly bartering for the malt for their whisky with a finished bottle of their stocks. Much of their moonshine even wound up in local hotels, although in the 1930s, some found its way into the hands of a freshly appointed Customs Inspector, who brought forth a number of indictments.

Eighty years later, New Zealand has righted the ship by permitting distilling once again. Southern Distilleries, Ltd. took them up on the offer and currently produces a range of single malts, blended malts, and moonshine. Not far away sits a freshly minted Hokonui Museum, with all sorts of memorabilia from a time when whisky-making was frowned upon in Kiwi Station.

The Hokonui Hills.

Sweden

In the 9th and 10th centuries, Vikings roamed the plains of southern Sweden, fortifying their guts with beer and mead to celebrate conquests as far away as the British Isles.

Swedish vikings sphere of influence circa 1000 A.D. Map courtesy of Victor Falk.

In the 15th century, the Swedish proceeded from mead into the realms of akvavit, a grain- or potato-based spirit that distillers flavor with dill, caraway seed, cardamom, and other botanicals. The Swedes often drink the spirit with smoked fish during summertime celebrations, and a popular Swedish saying suggests that akvavit “helps the fish swim down to the stomach”.

In the late 20th century, Sweden saw its first foray into whisky, when Swedish engineer Magnus Dandanell and friends banded together to form Mackmyra distillery. Since then, Sweden has enjoyed openings of at least 13 more distilleries, including Spirit of Hven (named after one of the Vikings of yore) and Box Distillery, the world’s northernmost whisky distillery. (They should consider a collaboration with Southern Distilleries, Ltd., no?)

Many of these distillers kiln their barley not only with peat, as the Scots do, but also with juniper, lending additional herbal notes to the drams. They also age many of their whiskies in Swedish oak, which lends spiciness to the final flavor profile.

http://www.whisky-pages.com/stories/swedish-whisky.htm

Taiwan

Dig into your memory banks and try to find the slimmest memory of the “bitter beer face” ad campaigns from the early 90s. Have you found it, this dusty memory, with its claim that bitter beer is the absolute pits? Now dig into the same memory banks for a company called “Sierra Nevada”. Ring a bell? That’s because they helped pioneer bitter beer with a suite of delicious pale ales through the years.

The result?

Even as recently as 2010, craft beer only had 10% of the total beer market share by volume. But in the past 6 years, we’ve seen it surge from this rather pedestrian 5%, to a 12% in 2015. (Source.) That’s greater than 20% growth per year. And when you factor in that craft beer costs more per six-pack, you see its share of the total retail dollar value of beer at an effervescent 22%.

You might say the same thing is happening in craft spirits in general, and specifically in another Pacific Rim nation just a hop, skip, and a thousand-mile jump from Japan: Taiwan.

The Taiwanese whisky tradition doesn’t span millennia like Scotland’s and Ireland’s, nor does it even reach back into the 1800s like Canada’s, Japan’s, and New Zealand’s. Rather, Taiwan’s first distillery, Kavalan, opened in 2005, put out its first bottle of single malt in 2008, and won World’s Best Single Malt at the World Whisky Awards in 2015.

A truly stratospheric ascent for the distillery, which is located in a rural county of Taiwan named after the indigenous peoples that pre-dated Chinese settlers by thousands of years.

Unlike many bourbon & cognac warehouses (like the French chai above), Kavalan stores its casks upright.

Tasmania

My first introduction to Tasmania came in the form of the Tasmanian Devil by way of the four-season TV show Taz-Mania. If adolescent memory serves me correctly, the omnivore emitted multiple series of guttural grunts each episode while confronting the age-old cartoon quandary of how to find more food.

Fortunately, Tasmania has far more to offer than a dim-witted creature the shape of a splatter-painting. The island lies just across the Bass Strait, a mere 150 miles from the Australian mainland and is, interestingly, the 26th-largest island in the world. Also, the winningest axe-wielder in history, David Foster, hails from the island. It’s conceivable he likes a dram.

Tasmania has a comparatively cool climate, similar to Scotland: Hobart, the capital of Tasmania has an average high of 62 and average low of 47, while Islay has an average high of 53 and average low of 44. Yet Tasmania has half as much rainfall as Scotland and one-tenth the sheep. (Though it does lay claim to a semi-famous woolly sheep named Shaun.)

Shaun was far woolier than even this fur-meister.

As a general rule, lower rain yields lower humidity, which results in a spicier spirit, and Tasmanian whiskies are no rule-breakers in this regard.

Sullivan’s Cove, Tasmania’s best-known distillery, produces a series of single malts with a flavor described as a “crescendo of dried spices, honey and fruitcake” with a “long, spicy, mouth-filling finish” (link).

Oh, and as a side note, one of the distillery’s drams was delicious enough to receive the coveted title of “World’s Best Single Malt Whiskey” by World Whiskies Awards in 2014.

Interested in a tour & tasting at our Atlanta distillery? That's great news! Book your tasting & tour below:

A knockout blow for Irish whiskey

A knockout blow for Irish whiskey

The Old Fashioned

The Old Fashioned