CRAFTED WITH CHARACTERS

A collection of our thoughts on whiskey, spirits

&

the world

Spirited Women Who’ve Run the World of Spirits

With International Women’s Day, we wanted to take a few moments to recognize some of the women who have helped shape the spirits landscape over the last century, ranging from Prohibition to modern-day.

Ninety-nine years ago, a bespectacled Ohio attorney who’d once been pitchforked by a drunk farmhand and a glacial Minnesotan with a mountain for a mustache guided the U.S. into one of its darkest ages. President Herbert Hoover called this era “a great social...experiment”. That was, of course, before the era abruptly ended thirteen years later. As you might have guessed, this Great Social Experiment was Prohibition. Or “Prohibition”, as anyone with a thirst for the bottle might have called it with a wink and a nod during the era. For speakeasies and locker clubs abounded in cities all across the country, catering to parched politicians and performance artists alike.

An International Women's Day Celebration

For International Women’s Day, we wanted to take a few moments to recognize some of the women who have helped shape the spirits landscape over the last century, ranging from Prohibition to modern-day.

Ninety-nine years ago, a bespectacled Ohio attorney who’d once been pitchforked by a drunk farmhand and a glacial Minnesotan with a mountain for a mustache guided the U.S. into one of its darkest ages. President Herbert Hoover called this era “a great social...experiment”. That was, of course, before the era abruptly ended thirteen years later. As you might have guessed, this Great Social Experiment was Prohibition. Or “Prohibition”, as anyone with a thirst for the bottle might have called it with a wink and a nod during the era. For speakeasies and locker clubs abounded in cities all across the country, catering to parched politicians and performance artists alike.

Meanwhile, “rum-running” entered the American lexicon as a euphemism for the tactics that spirited entrepreneurs used to evade authorities and get hooch into the hands of the people. Two of the most successful rum-runners during the era? A convoy-boat operator with the unassuming name of Marie Waite, and a pistol-wielding bosslady nicknamed “Cleo”, who hailed from the same state as the bespectacled attorney who ushered in the rum-running age: Ohio. Turns out, “women were far better bootleggers than men because many states had laws that made it illegal for male police officers to search women.” (Georgia Hopley, the first female Revenue agent, had this to say on the matter: “Their [women’s] detection and arrest is far more difficult than that of male lawbreakers.”)

The Bahama Queen of Whiskey

Gertrude Lythgoe was the tenth child of an English father and Scottish mother, a fitting lineage for a woman who would become one of the most successful Scotch whiskey runners during Prohibition. Spending some of her childhood as an orphan, she left her birth-state of Ohio, first for New York, then California, to work as a stenographer. Not long thereafter, she came within the orbit of a liquor exporter based in London.

After the passage of Prohibition in 1919, the exporter sent Lythgoe on special assignment to Nassau, Bahamas, to set up a wholesale liquor business. She wasted no time in opening their operations on Market Street. Sporting a pistol on her hip and poetry on her tongue, she earned the respect and admiration of her mostly male bootlegging peers, including the famed “Bill” McCoy. Earlier in life, her supposed similarity to Cleopatra earned her the nickname “Cleo”, and rum-running colleagues soon took the nickname to its logical conclusion by dubbing her “The Bahama Queen”.

Over the course of the next six years, she imported thousands of bottles of spirits into the United States. Though she was arrested on numerous occasions, the authorities could never get anything to stick, and she walked each time without ever receiving a conviction. Finally, in 1925, believing a “jinx” to be waiting in the wings for her, she retired from running whiskey across the Caribbean. “I just beat my jinx before it got me,” “Cleo” Lythgoe remarked the following year to the Milwaukee Journal. Taking an almost obituesque tone, the Journal wrote of her retirement:

A jinx has tracked her down, from her whisk(e)y throne in Nassau, through the most luxurious hotels of European capitals...to the loneliness of a New York hotel suite, where she came to hide from the world and recover her lost nerve and her health, attended only by her deaf mute sister.

Yet give up the ghost she had not, even if she’d given up the whiskey chase. She moved to Los Angeles and passed away in 1964 at the age of 86. Perhaps a multi-millionaire; or perhaps not. Nassau flags were raised to half-mast for days after her passing. It’s even rumored that “the British flag itself dipped in salute when, for the last time, she sailed from the Bahamas” during the height of Prohibition, to escape that jinx.

Whiskey in a Teacup, Rum in a Speedboat

Tom Waits may have considered his “Black Market Baby” to be whiskey in a teacup, but Marie Waite was anything but. Far from staying cool, she is rumored to have been both handy and unabashed in her use of firearms. After her husband Charles washed ashore near Miami in 1926, Marie assumed the mantle of leading the rum-running business he’d established, just months after Cleo Lythgoe had hung up her hooch boots. (Whether Charles died at the hands of a rum-running competitor, or in a shootout with the Coast Guard, is still a matter of debate.)

Based in Havana, “Spanish Marie” initially found success by transporting her cargo in a flotilla of four convoy boats -- three loaded with rum, one loaded with guns to fend off the Coast Guard. From these convoy boats, her employees offloaded the rum into 15 smaller contact boats, “the fastest in the business”, to run her rum anywhere from Palm Springs to Key West. At her peak, reports put her net worth at nearly $1 million. Her speed advantage, however, proved short-lived, as the Coast Guard upgraded their fleet and enabled them with radios.

But soon, Marie outfitted her boats with radios as well, and established an unlicensed radio-transmission station on Key West. Uttering seemingly random words in Spanish, her outfit evaded detection throughout the next hurricane season. Yet on March 12, 1928, authorities stumbled upon her and six accomplices in Coconut Grove, Florida, unloading whiskey, rum, champagne, and beer from her boat Kid Boots into a truck. They arrested her for the transportation of 5,526 bottles of alcohol. After posting a $500 bond, Marie skipped town. She was never heard from again.

The Women Making this Whole Thing Go

Back at the ranch (ASW) nearly a century later, we’ve been most fortunate to have two spirited women making this whole journey of ours go: Kelly Chasteen and Hallie Stieber. Both Georgia natives, their paths to whiskey were wide-ranging.

A Snellville native, Kelly -- whose teetotaler grandmother coincidentally shared the name Gertrude with the whiskey-running Bahama Queen mentioned earlier -- found a friend in Scotch-and-soda while at UGA and has been known to don a mean costume. If you’ve ever marveled at our tasting room’s design, reveled at a private event here, or traveled to ASW just for the fine assortment of locally crafted wares on our shelves, you can thank our Partner, Kelly Chasteen. Like a bootlegger of old, she has kept our whole enterprise going for months untold, sticking with it from the very beginning. Oh, and if you’re ever in a footrace with her, we highly recommend you stop immediately. She’s lightning quick and may or may not be regionally famous for outrunning the occasional gazelle.

A Marietta native, Hallie spent some of her childhood in that great bastion of cabbage patch-grown children, Cleveland, Georgia. Like Kelly, she stayed here in Georgia, the Empire State South, for her college days, before joining Empire State South in Midtown. Her palate led her to Kimball House, then on to Boccaluppo, where she managed the beverage program. Inspired by Negronis, Boulevardiers, and some of her other favorite classic cocktails, she crafts some mighty fine drinks and the events you get to enjoy them at.

Whiskey brings them together day in and day out. Not only because they work at a whiskey distillery. But also because they find it delicious -- Kelly predominantly bourbon, Hallie leaning more towards ryes and malts. We celebrate them (along with those spirited pioneers, Gertrude “The Bahama Queen” Lythgoe and “Spanish” Marie Waite) by raising a dram of whiskey. Thank y’all for all that you have done and continue to do.

Our 4 Year Journey to Duality Double Malt: The World's 1st Whiskey of Its Kind

Enter Duality, a testament to Justin’s 16 years of single-minded dedication to learning how to make some of the best craft booze in the world. Jim and Charlie met Justin over four years ago and immediately mapped out the idea for Resurgens. Hot on the heels of the idea for Resurgens, though, came Justin’s idea for a whiskey distilled from a mash of 50% malted barley and 50% malted rye. When he mentioned it to Jim one whiskey-sipping afternoon, Jim immediately coined the name “Duality”, a name that describes the dram better than any other could. Little did we know then that Duality is the first whiskey of its kind, anywhere in the world.

In following our progress through the years, you may have noticed a recurring theme: we rarely stick to a script, eschewing what’s conventional in favor of a trailblazing quest to remain true to our whiskey roots.

Our Start 7 Years Ago

When we prepared to first release American Spirit Whiskey seven years ago, we knew the uphill climb that awaited us with the little known category of spirit whiskey. But we liked the taste of the recipe we’d come up with, so instead of starting with vodka, we took a gamble with a clear whiskey. And though selling our clear whiskey for six years without a brown spirit as a portfolio mate could, with great accuracy, be described as “challenging”, or “tough sledding”, or “borderline madness”, we’re proud to look back and say that we remained true to our whiskey roots.

The Beginnings of Distillation at 199 Armour Drive

And when we began distilling on our ridiculously photogenic Scottish-style copper pot stills last year, we again parted with convention. The very first spirit we distilled was a whiskey of rye - but not cereal rye, which forms the basis of nearly all the ryes you find on the shelf today. Rather, malted rye, which uses the most pronounced form (malt) of the most flavorful grain (rye). As our fresh-distilled rye malt whiskey spent time in new oak barrels, it culminated in Resurgens, Atlanta’s first rye since Prohibition, and a unique one at that.

Photo credit: Chris Avedissian

Never ones to rest on our laurels, we next set out to create not just an Atlanta first like Resurgens, but a global first - one that we hope can help put Atlanta on the map internationally as a destination for world-class spirits.

The Blueprint for Duality

Enter Duality, a testament to Justin’s 16 years of single-minded dedication to learning how to make some of the best craft booze in the world. Jim and Charlie met Justin over four years ago and immediately mapped out the idea for Resurgens. Hot on the heels of the idea for Resurgens, though, came Justin’s idea for a whiskey distilled from a mash of 50% malted barley and 50% malted rye. When he mentioned it to Jim one whiskey-sipping afternoon, Jim immediately coined the name “Duality”, a name that describes the dram better than any other could. Little did we know then that Duality is the first whiskey of its kind, anywhere in the world.

An early prototype of the Duality type.

Hundreds of distilleries use 100% malted barley to create single malts the world over. Midleton in Ireland. Springbank in Scotland. Nikka in Japan. Us here in Georgia. And the list goes on.

Not to mention, a small but skilled handful of distilleries across the U.S. distill a mash of 100% malted rye to produce wonderfully unique whiskeys. In addition to us, San Francisco’s Anchor Distilling comes to mind.

But no distillery we've found has combined these two grains into a singularly flavorful whiskey distilled by pairing the traditional, Scottish-style double copper pot method with the Appalachian innovation of grain-in distillation. We’ve taken to calling Duality a “double malt”, in the most unique sense of the word(s).

We don't take the term “trailblazing” lightly. We wouldn't use it for what we're doing here if it weren't true. But, through all our years of challenging ourselves, pushing against our own personal limitations, we had - often unbeknownst to us - been setting the stage to push against the broader status quo’s limitations. In this case, the status quo of using malt only in the context of a conventional single malt crafted of malted barley.

A Defining Moment

Duality, then, represents for us a defining moment of sorts, arising from our team’s single-minded concentration on creating not only the best whiskey we can, but one that we hope serves as the touchstone whiskey for aspiring distillers in the years to come, much as Ireland’s Green Spot was for Justin nearly two decades ago.

Duality Double Malt, a whiskey that astounds writers and reviewers the world over with its flavor and finesse. A whiskey with a gorgeous label crafted with every bit of dual symbolism - including a quote from Shakespeare’s MacBeth - that we could pack into a single 5x4” piece of linen paper. And most importantly, a rich, complex whiskey with a dusting of smoke that helps you, our supporters, to forget - if even for just an hour - the trials and tribulations that life brings with it.

A fine label, indeed.

We would be honored for you to join us for this monumental release on Saturday, August 5, and share this finest of hours with us.

You may reserve your ticket to the release by following this link or clicking the button below.

Big News: We're Opening a 2nd Location

Seven years ago, we kicked our journey off in the humble confines of an Atlanta kitchen. We didn't know it then, but our first product, American Spirit Whiskey, was Atlanta's original Post-Prohibition whiskey brand and would soon gain a following around Atlanta as a perfect whiskey for those just getting into the category and others looking for an alternative to the common vodka. As the winds of change started to move Georgia's distillery laws in a favorable direction, we decided to start looking for a place to call our own - a place to locate our own distillery in the heart of our hometown making the spirit we'd loved since our days at the University of Georgia.

The Way Back

Seven years ago, we kicked our journey off in the humble confines of an Atlanta kitchen. We didn't know it then, but our first product, American Spirit Whiskey, was Atlanta's original Post-Prohibition whiskey brand and would soon gain a following around Atlanta as a perfect whiskey for those just getting into the category and others looking for an alternative to the common vodka. As the winds of change started to move Georgia's distillery laws in a favorable direction, we decided to start looking for a place to call our own - a place to locate our own distillery in the heart of our hometown making the spirit we'd loved since our days at the University of Georgia.

The Search

Our search took us all over the city: from West Midtown to Buckhead to, eventually, Third & Urban's Armour Yards, where we settled on a space in the same neighborhood that had originally attracted SweetWater Brewery, the Atlanta Track Club, and Fox Bros. BBQ. For the last year and with Athens, Georgia's craft booze legend Justin Manglitz at the helm, we've been distilling at our 199 Armour Drive distillery, combining traditional, Scottish-style copper pot stills with the Appalachian innovation of grain-in distillation - one of the few distilleries in the country taking such an approach.

The Westward Expansion

The last seven years since those humble days in an Atlanta kitchen, and the last year in our Armour Yards digs have brought with them untold sweat, stress, and the sacrifice known as sipping whiskey. Now, with our distilling maestro Justin Manglitz at the helm and the incredible support you've provided us since our Grand Opening last year, we've decided to set off headlong into the next leg of our whiskey expedition: a westward expansion.

As of this week, we have come to terms with Stream Realty to open our 2nd Atlanta location, The ASW Rickhouse, joining our craft brewing friends Monday Night Brewing and Wild Heaven in Atlanta's vibrant West End neighborhood. Not to mention, we'll also be able to stave off the type of hunger known to occasionally accompany whiskey consumption with Atlanta icons Honeysuckle Gelato and Doux South Pickles as neighbors.

Wes Jones, Honeysuckle Gelato's co-founder, had this to say about us joining the fun:

I’m thrilled that ASW Distillery will join the fun at Lee + White. Jim and Charlie have put together an incredible team, a group that will enhance the collaborative environment being created at Lee + White. We at Honeysuckle Gelato are looking forward to welcoming ASW to the West End's burgeoning food family.

When our current barrel house gradually then suddenly became saturated with barrels of delicious whiskey, we sought a space that would allow us to continue to play a role in Atlanta's spectacular resurgence, while expanding our storage capacity to help us in our endeavor to put Atlanta on the map for craft distilling. With Monday Night Brewing and Wild Heaven - the founders of whom we've been friends with for over a decade - joining the Lee+White development, the choice was easy, and obvious. Like deciding between whiskey and V8.

Monday Night’s Jonathan Baker expressed enthusiasm for ASW Distillery’s decision:

We’re excited to continue our friendship with ASW, in no small part because we’ll have a perfect spot to walk to after work for a whiskey or three. We started out as neighbors, living next door to each other and brewing in the garage, and now we get to be literal neighbors again.

Meanwhile, ASW Distillery’s Head Distiller, Justin Manglitz, has known Wild Heaven’s Brewmaster Eric Johnson for years, since Manglitz’s days owning downtown Athens, Georgia’s home brew supply store, where Eric was one of his biggest customers. Of ASW Distillery’s westward expansion, Wild Heaven’s Johnson noted:

We are thrilled that ASW has decided to officially become our neighbor in the exciting Lee+White development on the new West End Beltline. They are a perfect fit with the growing community of creatives who have decided to make L+W their home. They are long-time friends who make amazing spirits and we look forward to continuing our many collaborations with them in the years to come.

As such, The ASW Rickhouse will increase our total barrel storage capacity to nearly 1,500 barrels and will provide a convenient spot for our CEO Jim to take a nap, away from the watchful eyes of Justin.

The Other Great News

The timing could not be more right, either. Earlier this week, Governor Nathan Deal signed SB 85 into law that, among other things, allows distillery guests starting this September to sample any of our whiskies in either flight or cocktail form. So no more difficult choices as you peruse our six (and growing) spirits offerings.

The law represents a true game-changer for us and our craft brewery cousins, allowing us to thrive and continue to provide Georgians with a plethora of local craft options.

With all of these incredible encouraging developments fueling us forward, we could not be more excited to share this next, pioneering chapter in our history with you.

To that end, we would be most honored if you would kindly share this exciting news with your friends, on any of the below mediums:

Thank you so much for your ongoing support. We absolutely cannot do it without you and hope to continue to be able to share our journey with you over the weeks, months, and years to come.

The first of many great whiskies to come

Do y’all remember Atlanta’s original craft breweries? We’re talking Marthasville, formed in 1994; Atlanta Brewing Co., formed in 1994 and later renamed Red Brick Brewing Co.; Dogwood, formed in 1996; and of course, Atlanta’s biggest craft brewery to date, SweetWater, formed in 1997.

These were Atlanta’s craft beverage pioneers, paving the way for the incredibly rich and diverse craft beer scene we enjoy in Georgia today. Without their hard work and determination, Georgia’s libations landscape would be significantly less interesting. And we here at ASW Distillery would likely not have had a remote chance of trying to help put Atlanta on the map for craft whiskey.

Do y’all remember Atlanta’s original craft breweries? We’re talking Marthasville, formed in 1994; Atlanta Brewing Co., formed in 1994 and later renamed Red Brick Brewing Co.; Dogwood, formed in 1996; and of course, Atlanta’s biggest craft brewery to date, SweetWater, formed in 1997.

These were Atlanta’s craft beverage pioneers, paving the way for the incredibly rich and diverse craft beer scene we enjoy in Georgia today. Without their hard work and determination, Georgia’s libations landscape would be significantly less interesting. And we here at ASW Distillery would likely not have had a remote chance of trying to help put Atlanta on the map for craft whiskey.

We’ve joined just three other Atlanta-area craft distilleries in trying to provide you with spirits that you can call your own hometown spirits: from Lazy Guy’s bourbon & rye, to Old Fourth’s vodka & gin, to Independent’s rum & bourbon. Our own contribution ranges from two forthcoming bourbons, to brandies if fruit prices ever go back down, to single malts to write home about, made from 100% malted barley and 100% malted rye.

This last spirit, our single malt made from 100% malted rye, is one of just a handful in the country. But we didn’t make it just to be different. (Although we do like to blaze some trails and push some envelopes when we can - it's far better than pushing paper, which 2 of the team members did for many years.) We made it in homage to the single malts we’ve loved for years, fashioned on the same Scottish-style double copper pot stills that some of our favorite Scotch and Irish Whisk(e)y distillers have used for centuries. (Macallan, anyone?) We made it as a testament to one of Georgia’s native grains, rye, which has grown here for centuries. Far better than the European import known as barley.

Yet we also made our Single Malt Rye as a way to show the innovative flavor profiles you can achieve by experimenting with grains. Just like the craft beer pioneers before us — who showed how delicious heavily hopped beer can taste, and how damn good a sour ale brewed using wild, unpredictable yeast can be — we wanted to give Atlanta something unique to call its own, a style of delicious whiskey you find almost nowhere else in the U.S., let alone Georgia.

We’ve put most of it in new, American oak casks to mature for a later date. Not to mention, we enlisted the talents of one of Georgia’s best artists to design the label. More on that to come.

But in the meantime, we’ve bottled some of this groundbreaking Single Malt Rye before it spends time in oak. You’ll notice it’s incredibly smooth for the 93 proof we bottled it at, and has interesting notes of chocolate, hazelnut, and pepper. As it spends time in a barrel, it will take on some of the toffee, caramel, and vanilla notes you expect of a Highlands single malt, and may even present hints of Georgia’s terroir in its tasting notes, like cooked peaches and dried figs.

We look forward to sharing our spirits with you, helping put Atlanta on the map when it comes to craft distilling, and providing you with your very own hometown whiskey for years to come. Thank y’all for sharing in our journey.

Good Still Hunting: where Scottish tradition & Southern innovation meet

If you’ve followed us for a while, you know how much we dislike puns. They’re cheeky. They’re smarmy. They are, for lack of a better word, punny. Puns wore out their welcome long before Shakespeare, and then he went on a 37-play bender devoted almost entirely to their use. They are, for all intents and purposes, a comical anachronism. We hope everyone — most especially, our friends—comes to dislike puns as much as us.

If you’ve followed us for a while, you know how much we dislike puns. They’re cheeky. They’re smarmy. They are, for lack of a better word, punny. Puns wore out their welcome long before Shakespeare, and then he went on a 37-play bender devoted almost entirely to their use. They are, for all intents and purposes, a comical anachronism. We hope everyone — most especially, our friends—comes to dislike puns as much as us.

If not for Billy Shakes, puns would likely be a thing of the past.

That’s why we use puns as often as possible. Not because we love them and lack the wit that would carry us into comical kingdoms far beyond the realm of the purse-lipped pun. But purely for the benefit of humankind: to induce others to tire of puns as much as we did the first time we heard one.

In fact, even once all our friends tire of puns and pledge to discontinue their use, we’ll remain steadfast to our noble quest by continuing to use puns until anyone within a fortnight can’t stand to hear even one more. Because at that point, with no lame jokes left, they'll be able to concentrate fully on the great whiskey we've set out to make, an odyssey that started over six years ago and has finally culminated in our opening to the public.

In this installment of Crafted with Characters, which we’ve nobly entitled “Good Still Hunting”, we document our hunt for the perfect stills, the stills most suited to making the type of whiskey we want to make for years to come.

But first, a little background on the main types of stills available to whiskey-makers today.

Pot Stills

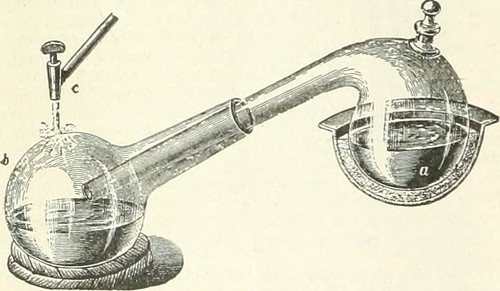

Pot stills are like Plato to the Socrates of the alembic still (which Miriam the Prophetess is said to have invented in the Middle East around the 2nd century A.D.). Whereas early alchemists used alembics chiefly for distilling non-consumables like rose water and perfume, pot stills were perfected for making whiskey.

An old pharmaceutical alembic, the Socrates of distilling systems.

Invented long before the printing press gave the thousands of novels that James Michener wrote each year a more widespread audience than the local cobbler, pot stills remain the chosen tool of the trade for single malt whiskey producers the world over: from Scotland to Canada to Japan to Australia.

But they're not chosen because they're easy. In fact, there's not any automation on traditional pot stills to speak of - they're operated entirely by manual levers, valves, and gauges.

Just as true sports car enthusiasts insist on a manual transmission, so too do many whisk(e)y makers insist on entirely manual pot stills.

If you're just getting into whiskey, an important distinction to know is this: single malt whiskies can generally only come from pot stills; blended whiskies and bourbons can come from either type of still, although often — especially in the case of the larger bourbon-makers — come from column stills.

Over the years, the single-malt-loving Scottish and Irish refined the pot still to become a copper-hewn sculpture of art. Consisting of a copper kettle heated from below, a tapered cone through which whiskey vapors pass — known as the swan’s neck, and a tube leading to a condenser — referred to as the lyne arm, pot stills produced the first whisk(e)y the world ever tasted.

At the most basic level, whiskey is made by heating something similar to an un-hopped form of beer to concentrate the ethanol and some of the flavors in the beer into more potent form.

To accomplish this, a pot still has an opening at the top of a kettle through which concentrated ethanol vapors pass into a tube surrounded by cold water. When the whiskey vapor that boils from the kettle passes through the tube touching cold water, the temperature of the vapor drops quickly, re-condensing the whiskey vapor back into liquid. Similar principle as how your glass of adult lemonade beads up when it’s hot outside.

Inefficient by design, a pot still distillation typically raise a 6–8% alcohol distiller’s beer to around 25–30% alcohol, known as “low wines”, during a first run through the wash still. This run relies on science: ethanol and whiskey flavors — known as congeners — boil at a lower temperature than water. So you can boil off and condense much of the ethanol and whiskey flavors before the boiling point of water is ever reached.

To make whiskey on pot stills, then, requires a second run through a spirit still to further concentrate the alcohol from 25–30% low wines to 65–70% "high wines" (or pre-dilution whiskey). This second run is where the art of distillation occurs, because the distiller must monitor the vapors coming off the stills to determine where to make “cuts” between what to throw out, what to further refine by redistilling it, and what to keep as liquid gold ready for the primetime known as a barrel.(1)

Our 500 gallon wash still and 300 gallon spirit still, standing resolute.

All the while, the swan’s neck design of a pot still allows enough separation between the whiskey vapor traveling up it and the liquid in the kettles below to hold back most of the heavier (and oft-less desirable) fusel oils that form during the fermentation process.

Some pot stills also contain a helmet like the Sci Fi astronaut masks you see above our stills that provide reductions in pressure as the spirit travels up the still, thus holding back additional higher-boiling compounds.(2) (Note that none of the stills we observed in Scotland’s famous Islay region — referred to amongst the team as the Phenol Crescent — has these helmets.)

People in the industry refer to this whole pot still process as “batch distillation” because each distillation happens in — perhaps surprisingly — batches. The constraint then, is how big your first still is, because you can only heat that much distiller’s beer to begin turning it into whiskey.

Column Stills

In contrast, continuous column stills have no such “batch” constraint.

Invented in 1828 by Scotsman Robert Stein, and perfected by Irishman Aeneas Coffey in the late 1830s (maybe that’s why there’s a rivalry?), who closed his Dublin-based Dock Distillery to sell his new still full time, column stills provide a more efficient method of distillation. Because they run continuously with no constraint of an individual kettle’s size, you can continue feeding distiller’s beer in them 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, pausing only to watch Jim Kelly come out of retirement and lose in the Super Bowl.

Whereas with pot stills, you pour in a set amount of mash, then heat it from below using an outside heating source, with column stills, you continuously pour in mash, then heat the mash from below with direct steam injection.

The injected steam heats the mash to its boiling point, carrying concentrated ethanol and flavors from the mash up to the next plate with it. Each plate in a column still further refines the distillate, with a whiskey distillery often sending the distillate into what is known as a doubler or a thumper.

This doubler or thumper operates similarly to a pot still, heating up the distillate to further refine it by removing some of the high-boiling compounds such as propanol and isobutanol.

In addition to the large bourbon distillers, efficiency-minded vodka-makers also use continuous column stills.

Why?

Because, instead of pulling off whiskey from these plates, they can allow the spirit to continue up a very tall column, further stripping out flavor at each plate until the vodka is the colorless, tasteless, and odorless liquid that U.S. regulations require.

Hybrid Stills

Hybrid stills use the same batch approach as pot stills, but with a plate column on top of the kettle, rather than the helmet, swan’s neck, and lyne arm you often find in a pot still. (There are exceptions.) Some distilleries using hybrid stills bypass the column portion when they want a spirit to take on attributes of a pot still distillate, and engage the column portion when they want the spirit to take on traits of a column still distillate.

A little about our stills

Continuing in the tradition of single malt Scotch distillers, we worked with Vendome Copper & Brass Works out of Louisville to design our own custom twin pot still system. Not surprisingly, these gleaming copper beauties produce robust, flavorful whiskey, just like you find in Scotland.

But we wanted these stills to have a character all their own. So in addition to the standard kettle of most single malt Scotch makers’ stills, we requested that Vendome add helmets atop both the wash and the spirit still. The same helmets that, as we saw earlier, help remove fusel oils during the distillation process.

We then combine this traditional Scottish-style distillation with Southern innovation, including grain-in distillation and the introduction of corn, rye, and new charred American oak into the equation.

The net result is a truly exceptional whiskey that, we believe, you won’t find anywhere else. (If your bias radar is starting to beep more rapidly, feel free to turn it off — it’s mis-firing.)

With respect to the innovation known as grain-in distillation, perhaps we should digress:

In 1800s Ireland and Scotland, distillers lived in a rather cool, damp climate. Perfect weather for sheep. And ducks. And barley.

While barley makes damn good beer and whisk(e)y, leaving the grains in during fermentation produces a veritable explosion of husks .

Apparently barley is the messy child of the grain world.(3)

So single malt Scotch producers undertake a process known as “lautering”, in which they filter out the grain solids before fermenting their non-alcoholic grain soup, or mash.

In the hot South, where European immigrants couldn’t grow barley worth salt, they turned to rye and corn. These grains are much tidier than barley when left in during the fermentation and distillation stages of production.

This is corn. Apparently, corn in the old days was gray.

“But won’t the grain solids scald the bottom of your copper kettle?” Great question you just hypothetically asked. The very non-hypothetical answer is: yes, but.

But what?

Well, we have an automatic stirring mechanism called an “agitator” that continually stirs the rye and corn we use in our production to prevent these grains from sticking and scalding our pot still. Similar to how you stir oatmeal when you cook it the 18th century way in a big pot.

So in essence, we create whiskies that combine the flavor from Scottish-style twin pot stills with the flavor that comes from Southern-style grain-in distillation. The result is pure deliciousness, a supernova of flavor - not to be confused with that most bossa nova of flavor, the whiskey daiquiri.

Last but certainly not least, we’d be remiss not to give credit to the unique condensers that each of our stills possess. (They’re like unique little snowflakes that cool down whiskey vapor into delicious whiskey liquid.)

Look closely at the above photo of our stills, and you’ll notice a copper tube above the brass bell jar on the left, and a pyrex tube with copper coils above the brass bell jar on the right.

The tube on the left is known as a “shotgun” or “tube-and-shell” condenser. Take a cross-section of the condenser, and you’ll see a number of tubes within the large copper tube, arrayed much like a Gatling gun. The whiskey vapor that travels off the left still passes through these tubes, indirectly coming into contact with cool water that we cycle through the big tube. This style of condenser is more efficient than the coiled copper “worm” condenser that distillers used in the early days of whisk(e)y-making. We figured it would be bad for business if we used the most inefficient method on *everything* we do at the distillery.

On the other hand, the spirit still condenser, to the right of the gold, bell jar-shaped spirit still, is one of only a handful in the country in which the dynamics are inverted. Whereas the cold water passes through the big copper tube on the left, in the right glass condenser, the cold water passes through the small copper U-lines. The whiskey vapor that passes from the lyne arm above the right still into the glass unit thus condenses before your very eyes.

We chose this style of condenser to provide whiskey enthusiasts with an immersive, multi-sensory experience during tours. What better way to accomplish this than to actually see the whiskey condensing?

Today’s day and age has seen whiskey demand skyrocket. Accompanying this surge in demand for the liquid itself has been a surge in demand for stills. Seeing this, we placed the order for our stills with Vendome long before we ever broke ground on our distillery.

Nearly two years in the making, the stills finally arrived in October 2015. Permitting took us into June 2016, when — at long last — we were finally able to turn them on and begin producing whiskey, and licitly at that. Stay tuned for more on the first production run. We’ve got a lot of great content lined up.

— — — — —

(1) What the distiller throws out is referred to as “foreshots”, what the distiller further refines are known as “heads” and “tails”, and what the distiller sends to a barrel is known as “hearts”.

(2) Owens, Bill, The Art of Distilling Whiskey, Moonshine, and Other Spirits, p. 29.

(3) Note that some craft booze-makers believe that leaving barley husks in during fermentation results in bitter tannins that would render whisk(e)y rather unpleasant to drink. We’ve conducted our own experiments and found that these tannins don’t carry over during distillation.

What makes American Spirit Whiskey clear anyways?

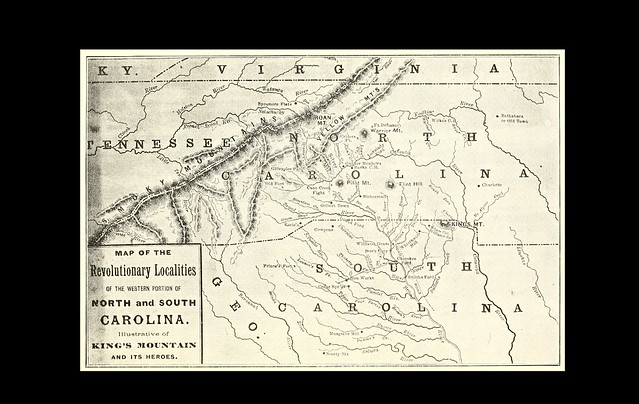

In the late 19th and early 20th century, a tinny-voiced man roughly the height of a chest of drawers dominated the moonshining scene of western North Carolina. Of Irish descent, his grandfather had fought in the Battle of King’s Mountain during the Revolution, a skirmish that President Theodore Roosevelt later described as the “turning point of the American Revolution”.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, a tinny-voiced man roughly the height of a chest of drawers dominated the moonshining scene of western North Carolina. Of Irish descent, his grandfather had fought in the Battle of King’s Mountain during the Revolution, a skirmish that President Theodore Roosevelt later described as the “turning point of the American Revolution”.

Out of necessity in the hardscrabble years leading up to the Civil War, Owens forewent formal schooling and, by age 14, had hired himself out as a “drawer of water and hewer of trees”. By the age of 23, his water-drawing skills had supplied him with enough money to buy 100 acres on Cherry Mountain, not far from Asheville, North Carolina.

Around that time, he transitioned from drawing water to distilling it, paying the justice of the peace who witnessed his marriage’s vows in brandy made from the cherry trees that grew abundantly on the slopes of Cherry Mountain. At its peak, the brandy-and-spice “cherry bounce” that Owens produced on his Cherry Mountain estate was served as far west as the Mississippi River.(1)

In Owen’s day —a period spanning from the era before Lincoln all the way through the first Ford motor vehicles — much of the spirits served were clear spirits. But the spirits enjoyed in his day and age were not the gin and vodka that came to dominate Prohibition and the post-War era. The spirits were whiskey and brandy, two spirituous elixirs normally associated with sepia tones.

Turns out that all spirits — whether gin, vodka, rum, or whiskey — leave a still as clear as a mountain creek or a conscience after bathing in one. It’s time in a barrel that gives most whiskey its brown hue — mainly from processes known as oxidation and extraction.

But if most whiskey is brown, why did we choose to roll out a clear whiskey as our first product? (Or “silver whiskey”, as some call it, similar to silver tequila.) As startups, craft distilleries have to concern themselves with cash flow, and often, the lack thereof. Socking away 100 barrels of bourbon for bottling in 4 years is all well and good, but in the meantime, you’ve got to figure out a way to keep the lights on.

That’s why so many craft distilleries of today bring a vodka or a gin to market first. Neither has to spend any time in a barrel, so a distillery can go from sacks of grain to filling glass bottles in less than a week. Compare that with the 12+ months needed to create a tasty bourbon — often much longer.

Not to mention, starting with vodka or gin means starting with a well-known category that doesn’t suffer from category-creation issues. So instead of having to educate thirsty drinkers on what exactly your product is, you can focus on what exactly differentiates your product from others on the market.

All of this adds up to a tried-and-true recipe for many startup distilleries, a wise move to ensure the lights stay on long enough to unveil the straight rye or sugarcane rum they’ve been aging all along.

We’ve always abided by the adage Do What you Love. You can truly tell the craft distillers who love gin from the care that goes into crafting their end-products. (St. George Botanivore, anyone?) At the same time, when we first created American Spirit Whiskey, we didn’t love vodka, or gin (we’ve since changed our minds on gin).

We did, however, love whiskey. We’d become well-acquainted with it since our days at the University of Georgia. We’d combed the City of Atlanta for our favorite bottles as they disappeared during the whiskey craze. We’d talked about the world at large while sipping it late into the evening.

So we decided that an unaged whiskey is where we’d devote our efforts. We knew the odds were against us — that we faced the category creation issues that have shut down concepts as wide-ranging as the Segway and the Sony MiniDisc. That we’d have to spend much of our days educating folks not just on what American Spirit Whiskey tasted like, but on how it was made, why you should try it, and, once a damn-that’s-good grin crossed their lips, what you could do with it. But adversity has never much deterred us, and so onward we marched.

And, as fortune favors the bold (or obstinate, as might be more applicable here), we are, almost six years later, on the verge of throwing open the doors to the distillery that will allow us to produce not only the spirit that got us here, American Spirit Whiskey, but many fine, aged spirits to come.

It hasn’t been easy. But we’re proud of sticking with clear whiskey when the sledding was tough - when we could have strayed from the path of doing what we love, but done so at the expense of feeling the true passion that comes with a calling. You might think of us as purists in the art form known as whiskey.

The art form began in the British Isles over 800 years ago, flowed west from the shores of Islay to the hills of the Appalachians, through the stills of that tinny-voiced moonshiner Amos Owens around the turn of the century, and, at long last, carved a course through the lives of all six of us at our distillery in the heart of Atlanta. We invite y’all to share the journey with us.

Buy our smooth-sipping silver whiskey online here.

----------

(1) Although we do not condone or associate with Owens' mindset - he served in the Confederacy during the Civil War - he is one of the most well-known moonshiners in American history and provides an example of the interest in grain-based clear spirits in times past. See Dabney, Joseph E., Mountain Spirits: A Chronicle of Corn Whiskey from King James' Ulster Plantation to America's Appalachians and the Moonshine Life, available here.