CRAFTED WITH CHARACTERS

A collection of our thoughts on whiskey, spirits

&

the world

Bourbon vs. Whiskey: What's the difference?

When you were in kindergarten, you likely weren’t a regular bourbon drinker. In fact, you probably didn’t yet know much about bourbon. This makes sense, as teachers are busy teaching you the basics of counting and cooperation, leaving little time to instruct you in the finer spirits of life. As you matured through the years like a fine bourbon in new charred American oak barrels, you likely developed a taste for Scotch, or bourbon, or rye whiskey. (We base this assumption on the fact that you’re here, and all we write about is whiskey.)

When you were in kindergarten, you likely weren’t a regular bourbon drinker. In fact, you probably didn’t yet know much about bourbon. This makes sense, as teachers are busy teaching you the basics of counting and cooperation, leaving little time to instruct you in the finer spirits of life. As you matured through the years like a fine bourbon in new charred American oak barrels, you likely developed a taste for Scotch, or bourbon, or rye whiskey. (We base this assumption on the fact that you’re here, and all we write about is whiskey.)

Yet sometimes our palates precede our knowledge. Many folks who’ve joined us for tours since we opened have oft-repeated the question: “So what’s the difference between bourbon and whiskey?”

Below is our attempt to answer this question as artfully as we can.

All bourbon is whiskey

Think back to your kindergarten days. Chocolate milk was a viable lunchtime beverage.

You got to nap every day. Scabs seemed to heal in twenty minutes. And you were taught that “all squares are rectangles, but not all rectangles are squares.” If you were like us, you probably pulled at your shirt and stretched your brain trying to understand this phrase. With these mental contortions in mind, we would like to reintroduce the metaphor to describe the difference between bourbon and whiskey:

All bourbon is whiskey, but not all whiskey is bourbon.

What exactly is whiskey?

In explaining this mind-blowing proposition, let’s first describe what whiskey is.

The U.S. TTB, the governing body of spirits in the U.S., basically says whiskey is:

- a distilled spirit,

- made from grain,

- bottled at 80 proof or higher, and

- distilled to less than 190 proof.*

(*Distilling grain, or any other base ingredient, to higher than 190 proof produces The Spirit Who Shall Not Be Named amongst whiskey enthusiasts — coincidentally, this 190+ proof spirit almost rhymes with Kafka and begins with the same letter as that other spirit not to be named by wizards, Voldemort.)

The TTB’s definition of whiskey seems straightforward enough, right? No specific grain requirement, no minimum aging requirement.

Yet, as with astrophysics and espionage, the devil lies in the details. For within such a straightforward-sounding definition, you can arrive at significantly different variations. From buttery whiskey brimming with toffee and chocolate, to chewy whiskey of citrus and clove, the flavor profiles you achieve can drastically change just by altering seemingly simple inputs — like the type of yeast you use, or the type of cask you age the spirit in.

And this is where the specifics surrounding bourbon come into play. Similar to the way changing the yeast or the type of cask lead to the same promised land known as delicious whiskey, changing the primary grain used to make whiskey to primarily corn leads us to the rolling pastures known as bourbon.

Bourbon is a subcategory of whiskey

Think of whiskey as a hub, and bourbon as a spoke. Whiskey is the parent category that gives rise to all other subcategories, including the bourbon that many have grown to love over the years.

To make bourbon, then, a U.S. distillery must follow all the requirements of making whiskey and, in addition, use at least 51% corn, distill to no higher than 160 proof, and age the newly made spirit in new, charred American oak casks (an invention that predates paper by 300 years). A couple other, more technical parameters apply as well, which you can check out here if you’re so inclined.

Note that, even with these additional requirements, bourbon still qualifies for the more general category of “whiskey” — it’s distilled from grain, distilled to less than 190 proof, and bottled at least at 80 proof.

Single malt is a more nebulous subcategory of whiskey

Similar to bourbon, a single malt is a subcategory of whiskey, albeit a more nebulous one.

What do we mean by nebulous?

Well, the TTB does not define a separate “single malt” classification, although we are, with other craft distilleries across the country, seeking to change this.

Single malt is thus a rather murky term that many distilleries are invoking when making a whiskey from malted grain, even when they combine various malted grains. (The “single” in single malt refers only to a single distillery, not to a single type of malted grain used.)

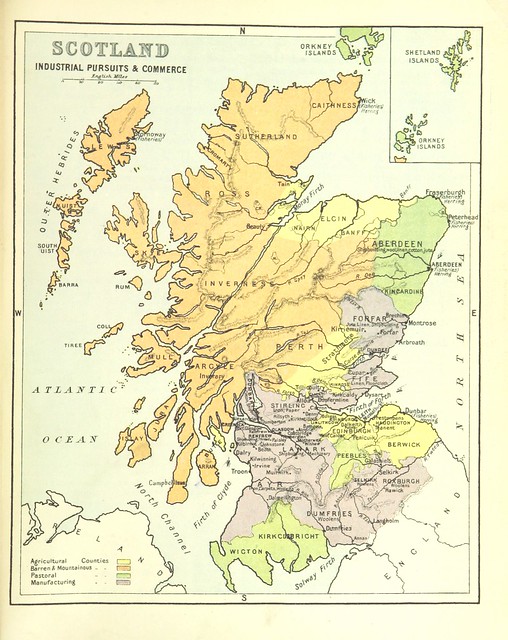

You’ve likely heard the term “Single Malt Scotch” before. Unlike the current use of “single malt” by U.S. distilleries, Scotland has clearly defined what constitutes a Single Malt Scotch.

The TTB defers to other countries’ definitions on many categories of geographically distinct spirits, including tequila and the more apropos Scotch that we’ve been discussing. So the TTB allows any Single Malt Scotch on the shelves of U.S. liquor stores if Scotland has given the producer the green light to call it Single Malt Scotch.

That means the only real definition of “single malt” comes from the sheep-laden glens of Scotland 4,000 miles away, which defines Single Malt Scotch as:

- Distilled from 100% malted barley

- Distilled to less than 189.6 proof

- Distilled in pot stills

- Aged at least 3 years

- Aged in oak (new or used)

Such a definition, and the time-honored distillation traditions in Scotland have, over the years, helped Scotch become the hallmark of quality when it comes to whisk(e)y-drinkers. (Though this wasn’t always the case.) That’s precisely why we seek to create a standardized, innovation-fostering subcategory of whiskey with the TTB this fall here in the States, a subcategory known as “American Single Malt Whiskey”.

Creating an American Single Malt Whiskey subcategory

Under today’s regime, when such single malt is from the U.S., how exactly the distillery made the whiskey (what grains they used, what types of stills they used) is more a mystery than Don King’s hair, unless the distillery specifies its production method on the label.

A well-crafted definition would ideally pick up all the best attributes of the Single Malt Scotch definition (especially the ability to age in new or used casks, which is currently the forbidden fruit of U.S. single malt distillers), while also fostering the innovation that helped the U.S. overtake France as the best wine-making region in the world in 1976 and ensured the U.S. led the world into the Brave New World of craft beer in the 1990s.

Just as lawmakers did in passing the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 and creating a definition for “straight whiskey” in the early 1900s — not surprisingly helping boost the image of America’s most well-known whiskey subcategory, bourbon, shortly thereafter — we have the chance to give American Single Malt an international reputation for quality.

All barrels are casks but not all casks are barrels

Casks are like the middle children of the aged spirits world. They don’t have the upscale industrial aura of the shining beacons of the spirits world — the stills that produce the spirits. Nor have they the multi-sensory appeal of the finished whiskey.

But casks play a huge role in helping shape the final flavor profile of not only spirits aged in them, but wine and beer, too. They can impart flavors as wide-ranging as vanilla, coconut, and oak, and — when charred on the inside — help charcoal filter the spirits into smooth-sipping glory.

Casks are like the middle children of the aged spirits world. They don’t have the upscale industrial aura of the shining beacons of the spirits world — the stills that produce the spirits. Nor have they the multi-sensory appeal of the finished whiskey.

But casks play a huge role in helping shape the final flavor profile of not only spirits aged in them, but wine and beer, too. They can impart flavors as wide-ranging as vanilla, coconut, and oak, and — when charred on the inside — help charcoal filter the spirits into smooth-sipping glory.

The first thing to know about “barrels” for spirits is that this term is not technically a catch-all for any vessel used to age spirits. Rather, a “barrel” is a specific term of art in the beverage industry referring to a 50–53 gallon (180–200 liter) cask, often made of white oak.

For the all-encompassing term for the vessel that you age spirits in, “cask” is the preferred nomenclature.

Kind of like how we learned in kindergarten that all squares are rectangles, but not all rectangles are squares, the same holds true here: all barrels are casks, but not all casks are barrels.

A definitive list of all different types of casks is available here, but the main types to know for the purposes of American whiskey are:

- Gorda — 185 gallons. Made from American oak. Their large size makes aging a long and arduous journey through the decades (less oak surface area coming into contact with the liquid), so these casks are perhaps best used to marry different whiskeys.

- Port Pipe — 172 gallons. With European oak as their base, these cylindrical (dare we say “pipe-like”?) casks first age port and often reinvent themselves as second use barrels in Scotch distilleries. More recently, American craft distillers have taken a liking to them in helping expand American whiskey’s flavor horizons.

- Sherry Butt — 126–132 gallons. For ages, Scotch (and some Irish whiskey) distillers have looked to ex-sherry casks to finish their distillates and create some damn fine Scotches: Glendronach 12, Glenfarclas 15, Aberlour 10. Finishing Scotch in sherry casks has become so popular that a cottage industry in Spain has sprung up to cooper these European oak, slender casks; age unmarketable sherry (i.e. low-grade) sherry in them for 3 years; then distill the sherry into Spanish brandy. (For a nice look at why Scotch boomed in the 20th century while Irish whiskey wilted, read on here.)

- Hogshead — 59–66 gallons. Made from ex-bourbon barrels, often repurposed. Used especially in Scotland, coopers make hogsheads by taking apart ex-bourbon barrels and reassembling them into slightly larger casks with new ends. The slightly larger size of the hogshead allows distillers to store more barrels per square foot in their rickhouses. From whence did these porcine vessels derive their name, you may ask? From a 15th century English term “hogges head”, a unit of measurement at the time equivalent to 63 gallons.

- American Standard Barrel — 50–53 gallons. Constructed from new American white oak or (less often) European oak, American Standard Barrels are the go-to cask used by the most well-known bourbon distillers like Four Roses and Heaven Hill. Craft distillers, on the other hand, have found success aging bourbon in the next cask on this list. (Wondering what exactly qualifies as bourbon? We read your mind and wrote about that here.)

- Quarter Cask — 13 gallons. Manufactured to precisely 1/4 the size of an American Standard Barrel, quarter casks provide distillers with a method by which to more quickly age distillates. Quarter casks are the same proportions as American Standard Barrels, but with 1/4 the amount of whiskey in each, the increased surface area of oak to liquid helps age whiskey more quickly. Notable proponents of the Quarter Cask include American craft distilling scion Tuthilltown with their Hudson Baby Bourbon, and esteemed Scotch producer Laphroaig.

- Barracoon — 1 gallon. Roughly the size of the small oak ASW barrels you may have seen in local bars or available for purchase in our shop, the amount of wood in contact with such a small volume of liquid seriously fast-tracks the aging process. Not always optimally, either.

I'm sure all of this has you wondering what types of casks we'll be using. Well, for starters, we'll try a combination of quarter casks and American Standard Barrels. As we build up stocks, we'll move to mostly American Standard Barrels. That said, we'll also roll out some unique finishing methods in the not-so-very-distant future. We'll reveal those later, so be sure to stay connected with us by signing up for our email list or following us on social media.

Cheers!

So what exactly makes bourbon, bourbon?

As we close in on the date we run our first bourbon through the stills, we thought it would be worthwhile to explore what exactly bourbon is, because lore and truth about our official spirit seem to have diverged in the snowy woods of time. With your permission, we’ll take the less-traveled road of truth on this one.

As we close in on the date we run our first bourbon through the stills, we thought it would be worthwhile to explore what exactly bourbon is, because lore and truth about our official spirit seem to have diverged in the snowy woods of time. With your permission, we’ll take the less-traveled road of truth on this one.

Made in the US

First things first, bourbon must be made in the US. That’s where the lawmakers have drawn the line. So does bourbon have to be made in Kentucky? No. That’s just what they’d like you to think. Rather, any distillery in the US — even that youngster, Hawaii (our 50th state), over two thousand miles off the California coast — can make bourbon.

And a number of non-Kentucky distilleries are making delicious ones, at that. Don’t believe us? Book a direct flight to Austin, Texas, then saddle up a vehicle and drive an hour due west to find out first hand at Garrison Brothers Distillery.

At least 51% corn

Next up, bourbon’s grain recipe must consist of at least 51% corn. This makes sense, as bourbon first originated around 1820 in the South, where corn grows with reckless abandon. The rest of bourbon’s grain recipe (the “mash bill” or “grain bill”) may consist of any other grain. Rye, barley, and wheat arethe most common. Note that there are two main styles of bourbon today: high rye and high wheat. The difference boils down to the secondary grain.

After corn, if a bourbon’s next most prominent grain is rye, it is, not surprisingly, considered a high rye bourbon. These are spicier and bolder. Examples include Four Roses, Jim Beam, and Bulleit (which was, until recently, made by Four Roses).

If a bourbon’s next most prominent grain after corn is wheat, it’s a high wheat bourbon. These are more rare and often have notes of salted caramel. Pappy Van Winkle, Maker’s Mark, and our first bourbon, Fiddler, all fall into this category.

Aged in new charred American oak

Third, bourbon must be aged in new charred American oak, most often in the form of a barrel. Note here that, though most people refer to all beer-belly-shaped vessels for aging whiskey as "barrels", “cask” is the more correct term in the industry. Why? Because “barrel” refers only to standard 53 gallon casks that most bourbon today is aged in, while some distilleries use 30 gallon or 15 gallon barrels/casks, known as “quarter casks”, or even casks that are bigger than the standard 53 gallon bourbon barrel if they so choose. (Although it wouldn’t be ideal, as bigger casks take more time to age whiskey.) Learn more about the various types of casks, including the American Standard Barrels oft-used for bourbon here.

Also notice that there’s no requirement for a minimum time spent in new charred American oak. So as soon as “white dog” — or newly made bourbon —touches the inside of a new, charred American oak cask, a distillery can call it a bourbon. But a mere week inside a cask often isn’t enough time to smooth out the otherwise rough-hewn new make. This is why most bourbon is aged at least one year. It’s not required, but palates the world over strongly encourage it.

One final thought on the charred barrels: by charring the inside, a cooper caramelizes parts of the oak known as the hemicellulose, lending flavors of chocolate and butterscotch, and lignins, lending vanilla characteristics. The charred interior also acts as a charcoal filter to shake the spirit down for all its hard edges as it passes in and out of the oak’s pores over the months.

The final two requirements for bourbon are a bit nerdier and more technical — both are requirements of proof, or alcohol by volume.

Distilled at no higher than 160 proof

To qualify as bourbon, the 51%+ corn spirit cannot be distilled higher than 160 proof, or 80% alcohol by volume. Why is this? Because Congress determined that, above 160 proof, a spirit starts to lose the bold and spicy characteristics that define a typical bourbon, becoming less distinctive in the process.

Put into barrels at no higher than 125 proof

The other proof requirement and final overall requirement stipulates that new make that would otherwise qualify as bourbon cannot enter a barrel at more than 125 proof. Why is this? Well, there you stumped us. But conjecture has always been a favorite pastime of ours. So we’ll speculate that a first-term Congressman from Missouri had, through the years, witnessed firsthand what slack demand can do for entire industries and decided to do something about during in the early 1900s.

What makes American Spirit Whiskey clear anyways?

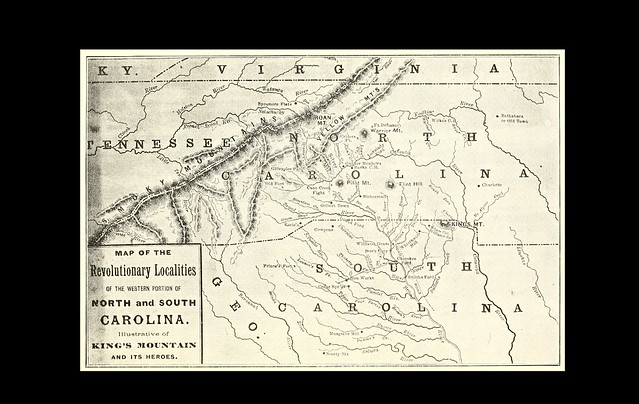

In the late 19th and early 20th century, a tinny-voiced man roughly the height of a chest of drawers dominated the moonshining scene of western North Carolina. Of Irish descent, his grandfather had fought in the Battle of King’s Mountain during the Revolution, a skirmish that President Theodore Roosevelt later described as the “turning point of the American Revolution”.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, a tinny-voiced man roughly the height of a chest of drawers dominated the moonshining scene of western North Carolina. Of Irish descent, his grandfather had fought in the Battle of King’s Mountain during the Revolution, a skirmish that President Theodore Roosevelt later described as the “turning point of the American Revolution”.

Out of necessity in the hardscrabble years leading up to the Civil War, Owens forewent formal schooling and, by age 14, had hired himself out as a “drawer of water and hewer of trees”. By the age of 23, his water-drawing skills had supplied him with enough money to buy 100 acres on Cherry Mountain, not far from Asheville, North Carolina.

Around that time, he transitioned from drawing water to distilling it, paying the justice of the peace who witnessed his marriage’s vows in brandy made from the cherry trees that grew abundantly on the slopes of Cherry Mountain. At its peak, the brandy-and-spice “cherry bounce” that Owens produced on his Cherry Mountain estate was served as far west as the Mississippi River.(1)

In Owen’s day —a period spanning from the era before Lincoln all the way through the first Ford motor vehicles — much of the spirits served were clear spirits. But the spirits enjoyed in his day and age were not the gin and vodka that came to dominate Prohibition and the post-War era. The spirits were whiskey and brandy, two spirituous elixirs normally associated with sepia tones.

Turns out that all spirits — whether gin, vodka, rum, or whiskey — leave a still as clear as a mountain creek or a conscience after bathing in one. It’s time in a barrel that gives most whiskey its brown hue — mainly from processes known as oxidation and extraction.

But if most whiskey is brown, why did we choose to roll out a clear whiskey as our first product? (Or “silver whiskey”, as some call it, similar to silver tequila.) As startups, craft distilleries have to concern themselves with cash flow, and often, the lack thereof. Socking away 100 barrels of bourbon for bottling in 4 years is all well and good, but in the meantime, you’ve got to figure out a way to keep the lights on.

That’s why so many craft distilleries of today bring a vodka or a gin to market first. Neither has to spend any time in a barrel, so a distillery can go from sacks of grain to filling glass bottles in less than a week. Compare that with the 12+ months needed to create a tasty bourbon — often much longer.

Not to mention, starting with vodka or gin means starting with a well-known category that doesn’t suffer from category-creation issues. So instead of having to educate thirsty drinkers on what exactly your product is, you can focus on what exactly differentiates your product from others on the market.

All of this adds up to a tried-and-true recipe for many startup distilleries, a wise move to ensure the lights stay on long enough to unveil the straight rye or sugarcane rum they’ve been aging all along.

We’ve always abided by the adage Do What you Love. You can truly tell the craft distillers who love gin from the care that goes into crafting their end-products. (St. George Botanivore, anyone?) At the same time, when we first created American Spirit Whiskey, we didn’t love vodka, or gin (we’ve since changed our minds on gin).

We did, however, love whiskey. We’d become well-acquainted with it since our days at the University of Georgia. We’d combed the City of Atlanta for our favorite bottles as they disappeared during the whiskey craze. We’d talked about the world at large while sipping it late into the evening.

So we decided that an unaged whiskey is where we’d devote our efforts. We knew the odds were against us — that we faced the category creation issues that have shut down concepts as wide-ranging as the Segway and the Sony MiniDisc. That we’d have to spend much of our days educating folks not just on what American Spirit Whiskey tasted like, but on how it was made, why you should try it, and, once a damn-that’s-good grin crossed their lips, what you could do with it. But adversity has never much deterred us, and so onward we marched.

And, as fortune favors the bold (or obstinate, as might be more applicable here), we are, almost six years later, on the verge of throwing open the doors to the distillery that will allow us to produce not only the spirit that got us here, American Spirit Whiskey, but many fine, aged spirits to come.

It hasn’t been easy. But we’re proud of sticking with clear whiskey when the sledding was tough - when we could have strayed from the path of doing what we love, but done so at the expense of feeling the true passion that comes with a calling. You might think of us as purists in the art form known as whiskey.

The art form began in the British Isles over 800 years ago, flowed west from the shores of Islay to the hills of the Appalachians, through the stills of that tinny-voiced moonshiner Amos Owens around the turn of the century, and, at long last, carved a course through the lives of all six of us at our distillery in the heart of Atlanta. We invite y’all to share the journey with us.

Buy our smooth-sipping silver whiskey online here.

----------

(1) Although we do not condone or associate with Owens' mindset - he served in the Confederacy during the Civil War - he is one of the most well-known moonshiners in American history and provides an example of the interest in grain-based clear spirits in times past. See Dabney, Joseph E., Mountain Spirits: A Chronicle of Corn Whiskey from King James' Ulster Plantation to America's Appalachians and the Moonshine Life, available here.

5 ways barrels are more impressive than a 7th grade science project

The surprisingly advanced technology known as the wooden cask dates back at least 2,500 years, when the Greek historian and world’s first investigative reporter, Herodotus, mentioned casks in relation to palm-wine. In fact, the technology probably predates Herodotus’ account by a number of years when considering that the craft of ship-building had relied on heating wood to bend and shape for a number of years prior.

The surprisingly advanced technology known as the wooden cask dates back at least 2,500 years, when the Greek historian and world’s first investigative reporter, Herodotus, mentioned casks in relation to palm-wine. In fact, the technology probably predates Herodotus’ account by a number of years when considering that the craft of ship-building had relied on heating wood to bend and shape for a number of years prior.

A barrel — which is a 53 gallon version of the more generic term, cask — consists of 3 main parts: the stave, the head, and the metal hoop. A stave is a wooden slat, bent through the application of moisture and heat, that, when grouped together, comprises the body of the barrel. The head is the circular cap on each end of the barrel. The metal hoop — usually six per barrel — is wedged onto the staves to hold them in their circular shape.

Economies of scale

The staves in a barrel are all be identical, thus allowing for mass-production. So casks were perhaps one of the first technologies to take advantage of economies of scale.

Ergonomics 101

Once the casks are assembled, they’re fairly cumbersome to move, especially by a solo practitioner. Yet casks are a clever lot: they shallowly bow out in the middle, allowing them to be rolled with minimal friction and turned on a dime, even by a single dock-worker. (We mention dock workers because casks of wine were often shipped from Spain and France to Holland starting in the 1600s, among other trade routes of varying degrees of civility.) Thus, long before the halcyon days of carpel tunnel and worker’s comp, casks are an early example of ergonomic design.

The glorious arch

When filled with bourbon, a barrel is a damn near unmanageable 500 pounds. A piece of cake for a World’s Strongest Man winner, perhaps, but think about how this must feel to those poor, wooden staves holding the liquid in. Yet casks rely on the geometric wizardry of the arch to distribute compression evenly through its entire structure. The ingenious arched shape of casks has thus preserved their survival on countless rough-and-tumble journeys through the canter of time. (Biased editor’s note — we’re willing to admit that UGA did not invent the arch.)

The original Lincoln logs

In part due to the metal hoops, a whiskey-maker can safely store a barrel on its side, which allows the distiller to stack barrels and preserve space. So barrels were like the original Lincoln logs, stackable units for efficient use of space.

Low sodium seasoning

Last but not least, most distillers who age spirits in casks the world over do so in casks made of oak. (A famous counterexample: Portuguese brandy-makers sometimes use chestnut casks.) Oak is remarkable for its unique combination of being malleable and structurally strong. But it’s perhaps even more remarkable for imparting flavors of vanilla, caramel, coconut, and over 400 other flavor compounds after a cooper caramelizes its sugars by charring its surface. Some whiskey experts claim that the cask imparts more than 50% of a whiskey’s final flavor. Thus, caramelized oak may be thought of as one of nature’s most complex seasonings, far superior to celery salt and even the esteemed saffron.

Speaking of well-seasoned whiskey, if you'd like to know when we release our newest bourbons and single malts, make sure to become a Supporting Reader:

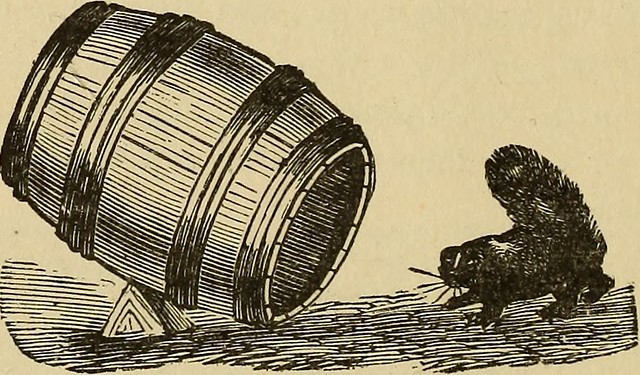

Honorable mention: catching vermin

Last but not least, we think the image below may be worth 1,000 words for another impressive attribute of barrels. Spoiler alert: they're great at catching squirrels.

A Bushmills sherry butt

A Bushmills sherry butt