Bourbon vs. Whiskey: What's the difference?

When you were in kindergarten, you likely weren’t a regular bourbon drinker. In fact, you probably didn’t yet know much about bourbon. This makes sense, as teachers are busy teaching you the basics of counting and cooperation, leaving little time to instruct you in the finer spirits of life. As you matured through the years like a fine bourbon in new charred American oak barrels, you likely developed a taste for Scotch, or bourbon, or rye whiskey. (We base this assumption on the fact that you’re here, and all we write about is whiskey.)

Yet sometimes our palates precede our knowledge. Many folks who’ve joined us for tours since we opened have oft-repeated the question: “So what’s the difference between bourbon and whiskey?”

Below is our attempt to answer this question as artfully as we can.

All bourbon is whiskey

Think back to your kindergarten days. Chocolate milk was a viable lunchtime beverage.

You got to nap every day. Scabs seemed to heal in twenty minutes. And you were taught that “all squares are rectangles, but not all rectangles are squares.” If you were like us, you probably pulled at your shirt and stretched your brain trying to understand this phrase. With these mental contortions in mind, we would like to reintroduce the metaphor to describe the difference between bourbon and whiskey:

All bourbon is whiskey, but not all whiskey is bourbon.

What exactly is whiskey?

In explaining this mind-blowing proposition, let’s first describe what whiskey is.

The U.S. TTB, the governing body of spirits in the U.S., basically says whiskey is:

- a distilled spirit,

- made from grain,

- bottled at 80 proof or higher, and

- distilled to less than 190 proof.*

(*Distilling grain, or any other base ingredient, to higher than 190 proof produces The Spirit Who Shall Not Be Named amongst whiskey enthusiasts — coincidentally, this 190+ proof spirit almost rhymes with Kafka and begins with the same letter as that other spirit not to be named by wizards, Voldemort.)

The TTB’s definition of whiskey seems straightforward enough, right? No specific grain requirement, no minimum aging requirement.

Yet, as with astrophysics and espionage, the devil lies in the details. For within such a straightforward-sounding definition, you can arrive at significantly different variations. From buttery whiskey brimming with toffee and chocolate, to chewy whiskey of citrus and clove, the flavor profiles you achieve can drastically change just by altering seemingly simple inputs — like the type of yeast you use, or the type of cask you age the spirit in.

And this is where the specifics surrounding bourbon come into play. Similar to the way changing the yeast or the type of cask lead to the same promised land known as delicious whiskey, changing the primary grain used to make whiskey to primarily corn leads us to the rolling pastures known as bourbon.

Bourbon is a subcategory of whiskey

Think of whiskey as a hub, and bourbon as a spoke. Whiskey is the parent category that gives rise to all other subcategories, including the bourbon that many have grown to love over the years.

To make bourbon, then, a U.S. distillery must follow all the requirements of making whiskey and, in addition, use at least 51% corn, distill to no higher than 160 proof, and age the newly made spirit in new, charred American oak casks (an invention that predates paper by 300 years). A couple other, more technical parameters apply as well, which you can check out here if you’re so inclined.

Note that, even with these additional requirements, bourbon still qualifies for the more general category of “whiskey” — it’s distilled from grain, distilled to less than 190 proof, and bottled at least at 80 proof.

Single malt is a more nebulous subcategory of whiskey

Similar to bourbon, a single malt is a subcategory of whiskey, albeit a more nebulous one.

What do we mean by nebulous?

Well, the TTB does not define a separate “single malt” classification, although we are, with other craft distilleries across the country, seeking to change this.

Single malt is thus a rather murky term that many distilleries are invoking when making a whiskey from malted grain, even when they combine various malted grains. (The “single” in single malt refers only to a single distillery, not to a single type of malted grain used.)

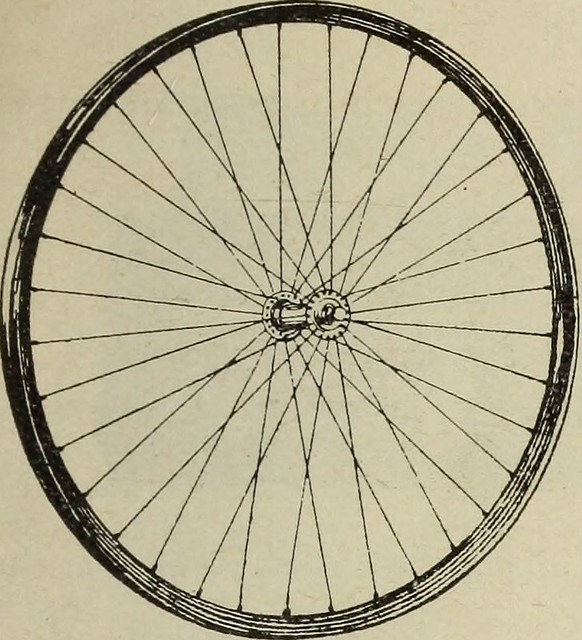

You’ve likely heard the term “Single Malt Scotch” before. Unlike the current use of “single malt” by U.S. distilleries, Scotland has clearly defined what constitutes a Single Malt Scotch.

The TTB defers to other countries’ definitions on many categories of geographically distinct spirits, including tequila and the more apropos Scotch that we’ve been discussing. So the TTB allows any Single Malt Scotch on the shelves of U.S. liquor stores if Scotland has given the producer the green light to call it Single Malt Scotch.

That means the only real definition of “single malt” comes from the sheep-laden glens of Scotland 4,000 miles away, which defines Single Malt Scotch as:

- Distilled from 100% malted barley

- Distilled to less than 189.6 proof

- Distilled in pot stills

- Aged at least 3 years

- Aged in oak (new or used)

Such a definition, and the time-honored distillation traditions in Scotland have, over the years, helped Scotch become the hallmark of quality when it comes to whisk(e)y-drinkers. (Though this wasn’t always the case.) That’s precisely why we seek to create a standardized, innovation-fostering subcategory of whiskey with the TTB this fall here in the States, a subcategory known as “American Single Malt Whiskey”.

Creating an American Single Malt Whiskey subcategory

Under today’s regime, when such single malt is from the U.S., how exactly the distillery made the whiskey (what grains they used, what types of stills they used) is more a mystery than Don King’s hair, unless the distillery specifies its production method on the label.

A well-crafted definition would ideally pick up all the best attributes of the Single Malt Scotch definition (especially the ability to age in new or used casks, which is currently the forbidden fruit of U.S. single malt distillers), while also fostering the innovation that helped the U.S. overtake France as the best wine-making region in the world in 1976 and ensured the U.S. led the world into the Brave New World of craft beer in the 1990s.

Just as lawmakers did in passing the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 and creating a definition for “straight whiskey” in the early 1900s — not surprisingly helping boost the image of America’s most well-known whiskey subcategory, bourbon, shortly thereafter — we have the chance to give American Single Malt an international reputation for quality.