CRAFTED WITH CHARACTERS

A collection of our thoughts on whiskey, spirits

&

the world

Spirited Women Who’ve Run the World of Spirits

With International Women’s Day, we wanted to take a few moments to recognize some of the women who have helped shape the spirits landscape over the last century, ranging from Prohibition to modern-day.

Ninety-nine years ago, a bespectacled Ohio attorney who’d once been pitchforked by a drunk farmhand and a glacial Minnesotan with a mountain for a mustache guided the U.S. into one of its darkest ages. President Herbert Hoover called this era “a great social...experiment”. That was, of course, before the era abruptly ended thirteen years later. As you might have guessed, this Great Social Experiment was Prohibition. Or “Prohibition”, as anyone with a thirst for the bottle might have called it with a wink and a nod during the era. For speakeasies and locker clubs abounded in cities all across the country, catering to parched politicians and performance artists alike.

An International Women's Day Celebration

For International Women’s Day, we wanted to take a few moments to recognize some of the women who have helped shape the spirits landscape over the last century, ranging from Prohibition to modern-day.

Ninety-nine years ago, a bespectacled Ohio attorney who’d once been pitchforked by a drunk farmhand and a glacial Minnesotan with a mountain for a mustache guided the U.S. into one of its darkest ages. President Herbert Hoover called this era “a great social...experiment”. That was, of course, before the era abruptly ended thirteen years later. As you might have guessed, this Great Social Experiment was Prohibition. Or “Prohibition”, as anyone with a thirst for the bottle might have called it with a wink and a nod during the era. For speakeasies and locker clubs abounded in cities all across the country, catering to parched politicians and performance artists alike.

Meanwhile, “rum-running” entered the American lexicon as a euphemism for the tactics that spirited entrepreneurs used to evade authorities and get hooch into the hands of the people. Two of the most successful rum-runners during the era? A convoy-boat operator with the unassuming name of Marie Waite, and a pistol-wielding bosslady nicknamed “Cleo”, who hailed from the same state as the bespectacled attorney who ushered in the rum-running age: Ohio. Turns out, “women were far better bootleggers than men because many states had laws that made it illegal for male police officers to search women.” (Georgia Hopley, the first female Revenue agent, had this to say on the matter: “Their [women’s] detection and arrest is far more difficult than that of male lawbreakers.”)

The Bahama Queen of Whiskey

Gertrude Lythgoe was the tenth child of an English father and Scottish mother, a fitting lineage for a woman who would become one of the most successful Scotch whiskey runners during Prohibition. Spending some of her childhood as an orphan, she left her birth-state of Ohio, first for New York, then California, to work as a stenographer. Not long thereafter, she came within the orbit of a liquor exporter based in London.

After the passage of Prohibition in 1919, the exporter sent Lythgoe on special assignment to Nassau, Bahamas, to set up a wholesale liquor business. She wasted no time in opening their operations on Market Street. Sporting a pistol on her hip and poetry on her tongue, she earned the respect and admiration of her mostly male bootlegging peers, including the famed “Bill” McCoy. Earlier in life, her supposed similarity to Cleopatra earned her the nickname “Cleo”, and rum-running colleagues soon took the nickname to its logical conclusion by dubbing her “The Bahama Queen”.

Over the course of the next six years, she imported thousands of bottles of spirits into the United States. Though she was arrested on numerous occasions, the authorities could never get anything to stick, and she walked each time without ever receiving a conviction. Finally, in 1925, believing a “jinx” to be waiting in the wings for her, she retired from running whiskey across the Caribbean. “I just beat my jinx before it got me,” “Cleo” Lythgoe remarked the following year to the Milwaukee Journal. Taking an almost obituesque tone, the Journal wrote of her retirement:

A jinx has tracked her down, from her whisk(e)y throne in Nassau, through the most luxurious hotels of European capitals...to the loneliness of a New York hotel suite, where she came to hide from the world and recover her lost nerve and her health, attended only by her deaf mute sister.

Yet give up the ghost she had not, even if she’d given up the whiskey chase. She moved to Los Angeles and passed away in 1964 at the age of 86. Perhaps a multi-millionaire; or perhaps not. Nassau flags were raised to half-mast for days after her passing. It’s even rumored that “the British flag itself dipped in salute when, for the last time, she sailed from the Bahamas” during the height of Prohibition, to escape that jinx.

Whiskey in a Teacup, Rum in a Speedboat

Tom Waits may have considered his “Black Market Baby” to be whiskey in a teacup, but Marie Waite was anything but. Far from staying cool, she is rumored to have been both handy and unabashed in her use of firearms. After her husband Charles washed ashore near Miami in 1926, Marie assumed the mantle of leading the rum-running business he’d established, just months after Cleo Lythgoe had hung up her hooch boots. (Whether Charles died at the hands of a rum-running competitor, or in a shootout with the Coast Guard, is still a matter of debate.)

Based in Havana, “Spanish Marie” initially found success by transporting her cargo in a flotilla of four convoy boats -- three loaded with rum, one loaded with guns to fend off the Coast Guard. From these convoy boats, her employees offloaded the rum into 15 smaller contact boats, “the fastest in the business”, to run her rum anywhere from Palm Springs to Key West. At her peak, reports put her net worth at nearly $1 million. Her speed advantage, however, proved short-lived, as the Coast Guard upgraded their fleet and enabled them with radios.

But soon, Marie outfitted her boats with radios as well, and established an unlicensed radio-transmission station on Key West. Uttering seemingly random words in Spanish, her outfit evaded detection throughout the next hurricane season. Yet on March 12, 1928, authorities stumbled upon her and six accomplices in Coconut Grove, Florida, unloading whiskey, rum, champagne, and beer from her boat Kid Boots into a truck. They arrested her for the transportation of 5,526 bottles of alcohol. After posting a $500 bond, Marie skipped town. She was never heard from again.

The Women Making this Whole Thing Go

Back at the ranch (ASW) nearly a century later, we’ve been most fortunate to have two spirited women making this whole journey of ours go: Kelly Chasteen and Hallie Stieber. Both Georgia natives, their paths to whiskey were wide-ranging.

A Snellville native, Kelly -- whose teetotaler grandmother coincidentally shared the name Gertrude with the whiskey-running Bahama Queen mentioned earlier -- found a friend in Scotch-and-soda while at UGA and has been known to don a mean costume. If you’ve ever marveled at our tasting room’s design, reveled at a private event here, or traveled to ASW just for the fine assortment of locally crafted wares on our shelves, you can thank our Partner, Kelly Chasteen. Like a bootlegger of old, she has kept our whole enterprise going for months untold, sticking with it from the very beginning. Oh, and if you’re ever in a footrace with her, we highly recommend you stop immediately. She’s lightning quick and may or may not be regionally famous for outrunning the occasional gazelle.

A Marietta native, Hallie spent some of her childhood in that great bastion of cabbage patch-grown children, Cleveland, Georgia. Like Kelly, she stayed here in Georgia, the Empire State South, for her college days, before joining Empire State South in Midtown. Her palate led her to Kimball House, then on to Boccaluppo, where she managed the beverage program. Inspired by Negronis, Boulevardiers, and some of her other favorite classic cocktails, she crafts some mighty fine drinks and the events you get to enjoy them at.

Whiskey brings them together day in and day out. Not only because they work at a whiskey distillery. But also because they find it delicious -- Kelly predominantly bourbon, Hallie leaning more towards ryes and malts. We celebrate them (along with those spirited pioneers, Gertrude “The Bahama Queen” Lythgoe and “Spanish” Marie Waite) by raising a dram of whiskey. Thank y’all for all that you have done and continue to do.

Foiled sieges and fake cats: the history of the modern bar

In 1920, a young Atlanta alderman by the name of William Hartsfield began reading speculative literature on the future of what many believed would become a way to transport mail faster. A few visionaries spotted the much more wide-reaching implications of this newfangled technology, the airplane. Hartsfield was one of them, and soon learned of the United States Postal Service’s plan to locate a refueling hub between its New York City and Miami airports for mail planes.

In 1920, a young Atlanta alderman by the name of William Hartsfield began reading speculative literature on the future of what many believed would become a way to transport mail faster. A few visionaries spotted the much more wide-reaching implications of this newfangled technology, the airplane. Hartsfield was one of them, and soon learned of the United States Postal Service’s plan to locate a refueling hub between its New York City and Miami airports for mail planes.

Hartsfield jumped at the opportunity, working together with then-Mayor Walter Sims to secure a five-year, rent-free lease on an abandoned racetrack known as the Atlanta Speedway. Hartsfield partnered with Atlanta’s chief of construction, W. A. Hansell, to transform the speedway into a proper airfield, sodding the field with truckloads of manure that caused an outcry from residents of the downfield town of Hapeville.

As the date the federal government planned to open bidding approached, Hartsfield turned his attention to gaining longer-term access to the land by naming the airstrip Candler Field, a sycophantic ploy to win the loyalty of Asa Candler Jr., who held title to the land. Unswayed by flattery, the eccentric Candler — of Coca-Cola lineage who kept a menagerie of wild animals at his mansion — ensured Hartsfield he would demand payment in full for the property when the five-year lease ended.

When bidding for the postal service refueling station finally opened in 1926, Atlanta submitted its bid with bated breath. To Hartsfield’s chagrin, Atlanta’s westerly neighbor Birmingham submitted a bid for the refueling hub as well. At the time, the cities were nearly identical in regional influence and size, at around 200,000 residents apiece. And Birmingham was perhaps even more strategically located when one examined a map.

Hartsfield went to work, organizing a trip for an assistant postmaster general to visit Atlanta and inspect Candler Field. When the assistant arrived, Hartsfield ferried him across the city with a motorcade flanked by an eight-motorcycle escort. That evening, the scion of Atlanta’s banking community, John K. Ottley(1), Mayor Sims, Georgia Governor Clifford Walker, and Hartsfield, among many others, wined and dined the official before sending him off to a luxury hotel suite for the evening. As Hartsfield later gloated, “No east Indian potentate ever got the attention he did.”

A week later, the Commerce Department designated Atlanta as a stop on the federal airmail route. Hartsfield had, almost singlehandedly, paved the way for Atlanta to become the South’s — and, later, the nation’s — busiest flight hub, connecting millions of national and international visitors every year.(2)

Three centuries before airports became symbols of a city’s connectedness and Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport put Atlanta on the map internationally, Vienna and London were in the midst of their own connectivity renaissances. Unlike the twentieth century’s hubs, in which visitors speaking languages of all stripes sipped lattes and lagers while reading the New York Times between flights, Vienna’s cafes and London’s gin joints were far more provincial in nature. Yet they, like the airport, brought far-flung citizens together like never before.

A siege before the caffeine surge

The Ottoman Empire once stretched from the Persian Gulf in the east to the piedmont just west of Venice’s canals, a distance the equivalent of Atlanta to San Francisco. At the height of its imperial efforts, the Ottoman Empire made multiple attempts to sack the Habsburg Dynasty’s cultural hub of Vienna — first in 1529, another in 1683. Each time, the Viennese rebuffed the onslaught by the Ottoman troops. The story goes that in the aftermath of the Second Siege of Vienna, the Viennese found sacks of strange beans they originally believed to be camel feed. Rather than disposing of the beans, Polish king Jan III Sobieski, who had helped defend Vienna, gave them to one of his officers, Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki — the uncanny resemblance to the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, be damned.

It was the first time on record coffee had made its way to Europe — it was welcomed with as much aplomb as tobacco had been received on Columbus’ return from the “West Indies” 200 years prior. Kulczycki soon opened Vienna’s first coffeehouse.

Cafe Griensteidl: the First Starbucks?

The next 200 years saw Vienna’s coffeehouse culture grow and thrive. So much so that “by 1900 they had evolved into informal clubs, well furnished and spacious, where the purchase of a small cup of coffee carried with it the right to remain there for the rest of the day…Newspapers, magazines, billiard tables, and chess sets were provided free of charge, as were pen, ink, and (headed) writing paper.”(3)

These caffeinated social clubs helped distinguish Vienna from other cultural centers like Berlin, Paris, and London — the last of which was, concurrent to the Viennese cafes, pronouncedly more besotted, as we’ll explore below.

The most famous of Vienna’s coffeehouses, Cafe Griensteidl, saw many influential authors and philosophers of the early 1900s enjoy a cuppa, including, Hugo von Hoffmansthal, Theodor Herzl, and likely Sigmund Freud himself, although he found Vienna provincial and preferred Swiss cities.

Today, we still enjoy the legacy of these Viennese coffeehouses when we order a latte at a Starbucks coffee bar, pour half the contents out, and fill the space with whiskey from a hip flash that we carry around in our left boot. Our cafes today carry a mantle borne down through the ages by West Coast entrepreneurs, who perfected the Viennese model by adding a dash of indie music and bespoke-seeming branding before scaling the concept to the rest of the world.

The rise of the London dram shop

Five years after Kulcynski opened Vienna’s first coffeehouse, achipelagic Europeans — Londoners, more specifically — got their first taste of gin when William of Orange acceded to the throne. For years, French brandy had been the British spirit of choice, but political and religious conflict between the cross-Channel neighbors led the British Government to pass various acts restricting brandy imports. In 1690, the Government ended the monopoly held for years by the London Guild of Distillers. A range of distillers dove headfirst into the deep ends of the gin pool, encouraged by various politicians, including Queen Anne herself.

As more efficient industrial agriculture practices drove food prices down, Brits — especially cosmopolitan Londoners — had more disposable income. Lacking bowling alleys and Bieber concerts, Londoners took to drink as a form of communal gathering. Centuries prior, visionary entrepreneurs had foreseen that many Brits preferred to down their drinks away from the confines of their homes and had thus introduced thousands of taverns, inns, and alehouses across the country. There, patrons would gather around rough-hewn tables to drink tankards of ale and presumably plot coups that never made it past midnight.

Gin joints & miserable livers

Gin revolutionized these parochial gathering places. Instead of serving patrons at picnic tables, the proprietors of “dram shops”, as they came to be called, centralized distribution of beverages at a main bar. These “gin joints” blossomed throughout the early 1700s, and Brits’ spirits consumption tripled. As early as 1721, Middlesex magistrates decried the pervasive drunkenness they witnessed in the streets. Moving swiftly, they helped pass the Gin Act of 1736, which taxed retail sales of gin at 20 shillings a gallon and required gin joint proprietors to pay a £50 annual license — roughly £7,000 at today’s rates — all but pricing out everyone in the market.

Wily barkeeps introduced an ingenious mechanism to circumvent the de facto prohibition imposed by the 1736 Gin Act. Thirsty Londoners would deposit a shilling in a cat’s paw outside of an unassuming residence. The shilling traveled down a tube, and when the barkeep inside received the money, the barkeep would pour a shot’s worth of gin down the tube to the patron’s mouth. Thus was born the precursor to two 20th century innovations: the Prohibition-style speakeasy, and the modern-day ice luge.

Old Tom Gin & Prohibition-era preferences

The gin-paw invention was known as “Old Tom” — an homage to the tom cat that served as gin courier. In time, gin earned the nickname “Old Tom” as well, specifically a type of sweeter gin. The name still stands today with brands like Ransom Old Tom Gin and Anchor Old Tom Gin leading the craft spirits category.

A century after the first gin joints opened, they resurfaced serving not just gin, but wine and beer as well. They were the precursor to the modern bar as we know it.

Of course, the party didn’t truly start until proprietors added whiskey to the fray. By the time the U.S. enacted that Great Failed Experiment, Prohibition, in 1920, rye whiskey had replaced cognac as the spirit of choice, planting itself firmly in the minds of thirsty bar-goers. Prohibition was to the whiskey industry nothing short of an earthquake — a rifting of plates, a shifting of palates.

Post-Prohibition plate tectonics

In the winner’s circle: Blended Canadian whiskey, with its mild manners and smooth finish, vaulted like an Olympic gymnast into the minds of consumers. Not to mention:

In the post-Prohibition era, bourbon proved as resilient as the corn it derived from.

Not making the podium: Rye whiskey fell off the bar stool, and nearly off the map. Irish whiskey, in the wake of Prohibition and the 1919 closure of British markets, almost went extinct entirely.

A modern-day renaissance

But today, we’re seeing many delicious pre-Prohibition styles of spirit make a comeback. Old Tom Gin and its more mature cousin, barrel-aged gin, are seeing glimmers of shelf space. Irish whiskey is in the throes of a real heater. And perhaps most warming to us: rye whiskey is in the midst of a renaissance.

Why so warming to us? Because the first spirit off our Scottish-style twin copper pot stills is no less than a whiskey made from 100% malted rye, one of America’s native grains.

While we’ve barreled 95% of this American Single Malt Rye, we’ve chosen a select number of bottles to release to you, our early supporters. This one-time-only release offers a taste of delicious chocolate, hazelnut & pepper notes before the single malt spends time maturing in new American oak casks to become what may very well be the quintessential Southern single malt whiskey.

Join us for BBQ, Bluegrass, and Our First Bottle Release on Saturday, September 10 to help us celebrate this milestone for what we hope may very well become the quintessential Southern single malt whiskey and help put Atlanta on the map when it comes to craft whiskey.

Not to mention, each pass comes with a tour of the production area, including our gorgeous, hand-hammered copper pot stills and our rickhouse full of new American oak barrels.

We hope you’re as excited about this monumental event as we are.

— — — — —

(1) Our neighbor street in Armour Yards is Ottley Drive.

(2) Allen, Frederick, Atlanta Rising, Taylor Trade Publishing (1996)

(3)Watson, Peter, The Modern Mind: An Intellectual History of the 20th Century, Harper Collins (2011).

Bourbon vs. Whiskey: What's the difference?

When you were in kindergarten, you likely weren’t a regular bourbon drinker. In fact, you probably didn’t yet know much about bourbon. This makes sense, as teachers are busy teaching you the basics of counting and cooperation, leaving little time to instruct you in the finer spirits of life. As you matured through the years like a fine bourbon in new charred American oak barrels, you likely developed a taste for Scotch, or bourbon, or rye whiskey. (We base this assumption on the fact that you’re here, and all we write about is whiskey.)

When you were in kindergarten, you likely weren’t a regular bourbon drinker. In fact, you probably didn’t yet know much about bourbon. This makes sense, as teachers are busy teaching you the basics of counting and cooperation, leaving little time to instruct you in the finer spirits of life. As you matured through the years like a fine bourbon in new charred American oak barrels, you likely developed a taste for Scotch, or bourbon, or rye whiskey. (We base this assumption on the fact that you’re here, and all we write about is whiskey.)

Yet sometimes our palates precede our knowledge. Many folks who’ve joined us for tours since we opened have oft-repeated the question: “So what’s the difference between bourbon and whiskey?”

Below is our attempt to answer this question as artfully as we can.

All bourbon is whiskey

Think back to your kindergarten days. Chocolate milk was a viable lunchtime beverage.

You got to nap every day. Scabs seemed to heal in twenty minutes. And you were taught that “all squares are rectangles, but not all rectangles are squares.” If you were like us, you probably pulled at your shirt and stretched your brain trying to understand this phrase. With these mental contortions in mind, we would like to reintroduce the metaphor to describe the difference between bourbon and whiskey:

All bourbon is whiskey, but not all whiskey is bourbon.

What exactly is whiskey?

In explaining this mind-blowing proposition, let’s first describe what whiskey is.

The U.S. TTB, the governing body of spirits in the U.S., basically says whiskey is:

- a distilled spirit,

- made from grain,

- bottled at 80 proof or higher, and

- distilled to less than 190 proof.*

(*Distilling grain, or any other base ingredient, to higher than 190 proof produces The Spirit Who Shall Not Be Named amongst whiskey enthusiasts — coincidentally, this 190+ proof spirit almost rhymes with Kafka and begins with the same letter as that other spirit not to be named by wizards, Voldemort.)

The TTB’s definition of whiskey seems straightforward enough, right? No specific grain requirement, no minimum aging requirement.

Yet, as with astrophysics and espionage, the devil lies in the details. For within such a straightforward-sounding definition, you can arrive at significantly different variations. From buttery whiskey brimming with toffee and chocolate, to chewy whiskey of citrus and clove, the flavor profiles you achieve can drastically change just by altering seemingly simple inputs — like the type of yeast you use, or the type of cask you age the spirit in.

And this is where the specifics surrounding bourbon come into play. Similar to the way changing the yeast or the type of cask lead to the same promised land known as delicious whiskey, changing the primary grain used to make whiskey to primarily corn leads us to the rolling pastures known as bourbon.

Bourbon is a subcategory of whiskey

Think of whiskey as a hub, and bourbon as a spoke. Whiskey is the parent category that gives rise to all other subcategories, including the bourbon that many have grown to love over the years.

To make bourbon, then, a U.S. distillery must follow all the requirements of making whiskey and, in addition, use at least 51% corn, distill to no higher than 160 proof, and age the newly made spirit in new, charred American oak casks (an invention that predates paper by 300 years). A couple other, more technical parameters apply as well, which you can check out here if you’re so inclined.

Note that, even with these additional requirements, bourbon still qualifies for the more general category of “whiskey” — it’s distilled from grain, distilled to less than 190 proof, and bottled at least at 80 proof.

Single malt is a more nebulous subcategory of whiskey

Similar to bourbon, a single malt is a subcategory of whiskey, albeit a more nebulous one.

What do we mean by nebulous?

Well, the TTB does not define a separate “single malt” classification, although we are, with other craft distilleries across the country, seeking to change this.

Single malt is thus a rather murky term that many distilleries are invoking when making a whiskey from malted grain, even when they combine various malted grains. (The “single” in single malt refers only to a single distillery, not to a single type of malted grain used.)

You’ve likely heard the term “Single Malt Scotch” before. Unlike the current use of “single malt” by U.S. distilleries, Scotland has clearly defined what constitutes a Single Malt Scotch.

The TTB defers to other countries’ definitions on many categories of geographically distinct spirits, including tequila and the more apropos Scotch that we’ve been discussing. So the TTB allows any Single Malt Scotch on the shelves of U.S. liquor stores if Scotland has given the producer the green light to call it Single Malt Scotch.

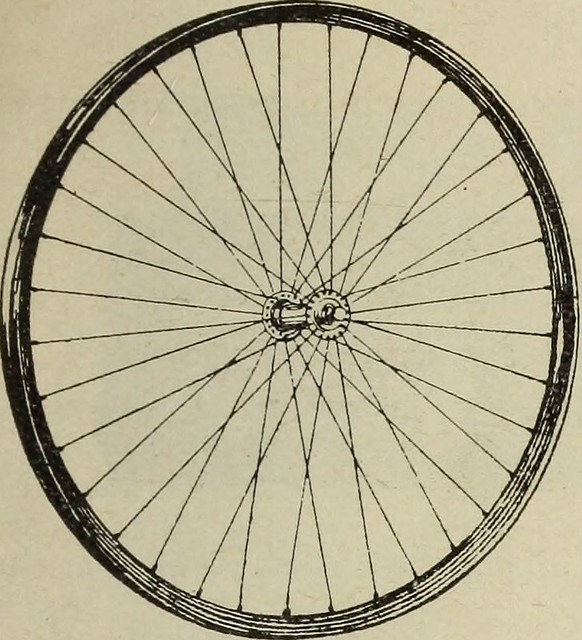

That means the only real definition of “single malt” comes from the sheep-laden glens of Scotland 4,000 miles away, which defines Single Malt Scotch as:

- Distilled from 100% malted barley

- Distilled to less than 189.6 proof

- Distilled in pot stills

- Aged at least 3 years

- Aged in oak (new or used)

Such a definition, and the time-honored distillation traditions in Scotland have, over the years, helped Scotch become the hallmark of quality when it comes to whisk(e)y-drinkers. (Though this wasn’t always the case.) That’s precisely why we seek to create a standardized, innovation-fostering subcategory of whiskey with the TTB this fall here in the States, a subcategory known as “American Single Malt Whiskey”.

Creating an American Single Malt Whiskey subcategory

Under today’s regime, when such single malt is from the U.S., how exactly the distillery made the whiskey (what grains they used, what types of stills they used) is more a mystery than Don King’s hair, unless the distillery specifies its production method on the label.

A well-crafted definition would ideally pick up all the best attributes of the Single Malt Scotch definition (especially the ability to age in new or used casks, which is currently the forbidden fruit of U.S. single malt distillers), while also fostering the innovation that helped the U.S. overtake France as the best wine-making region in the world in 1976 and ensured the U.S. led the world into the Brave New World of craft beer in the 1990s.

Just as lawmakers did in passing the Bottled-in-Bond Act of 1897 and creating a definition for “straight whiskey” in the early 1900s — not surprisingly helping boost the image of America’s most well-known whiskey subcategory, bourbon, shortly thereafter — we have the chance to give American Single Malt an international reputation for quality.

Cognac was the Scotch of the 1800s. What happened?

At sunrise in December 1861, with soldiers staving off pneumonia, Union General Robert H. Milroy led his troops across a snow-covered rocky meadow against an entrenched Confederate force. Even as the sun slowly flared to life amidst the iron clouds, the wind at the crest of Allegeny Mountain in Virginia’s western barrens kept up its relentless howling. Against the piercing gale, Union troops advanced throughout the morning. But as the clock tipped past noon, Confederate troops unleashed a barrage of artillery fire that drove the Union soldiers into retreat on Cheat Mountain. The war would continue — largely in stalemate — for almost four more years.

At sunrise in December 1861, with soldiers staving off pneumonia, Union General Robert H. Milroy led his troops across a snow-covered rocky meadow against an entrenched Confederate force. Even as the sun slowly flared to life amidst the iron clouds, the wind at the crest of Allegeny Mountain in Virginia’s western barrens kept up its relentless howling. Against the piercing gale, Union troops advanced throughout the morning. But as the clock tipped past noon, Confederate troops unleashed a barrage of artillery fire that drove the Union soldiers into retreat on Cheat Mountain. The war would continue — largely in stalemate — for almost four more years.

It’s hard to imagine a more different scene than what was happening five hundred miles to the north, behind the plate-glass windows of a saloon in cobblestoned, not-quite-quaint Manhattan. A certain Jerry Thomas was writing the nation’s first book on mixology.

“Professor” Jerry Thomas grew up on the Canadian border in Sackets Harbor, New York, before learning the craft of bartending in New Haven, Connecticut. From New Haven, he traveled west for the California gold rush in 1849 — one of the men whose toil gave rise to the name of San Francisco’s pro football team over a century later. He soon gave up mining and hung his shingle managing a minstrel show for the rough-shaven and rougher-languaged pioneers.

Two years later, he hung up his mining-camp boots and returned east to Manhattan. There, he opened up a number of saloons near the southern end of the island. At the time, Manhattan’s 500,000 residents traversed the city via a network of muddy roads, especially towards the less-developed northern end of the island . (In 1857, Frederick Law Olmstead finally landscaped some of this mud into what later became one of the more breathtaking sets for Home Alone 2: Central Park.) Professor Thomas’ south Manhattan saloons proved successful, affording him the opportunity to take up work as a bartending troubadour and travel to New Orleans, Chicago, and even Europe with a set of solid-silver bar tools.

By the time The Civil War began in April of 1861, Jerry Thomas had earned his famous nickname “Professor” and had begun work on the U.S.’ first ever cocktail book. Published as How to Mix Drinks, or The Bon Vivant’s Companion in 1862 and still referenced heavily today, over 150 years later, it seems unlikely the Professor knew quite how influential his book would eventually become. No matter to him, though, for he appreciated a well-prepared drink like few could, and simply wanted to spread his wealth of knowledge.

With the cold December day in 1861 pressing down on him, troops battling to the south, Professor Thomas imagined warmer climes, seeking to concoct a boozy tipple perfect for the spring that couldn’t come fast enough.

The recipe he arrived at was the Georgia Mint Julep. Originally styled for a cut-glass goblet, rather than a pewter cup, the recipe called for mint, sugar, crushed ice, and…not bourbon. Rather, the recipe called for brandy (and lots of it). Specifically, the julep-preparer was to summon 1.5oz of that most French of spirits, Cognac, into the glass.

Sacrilege, yes?

Not quite. At the time, bourbon hadn’t yet achieved its status as America’s Native Spirit. (That didn’t happen until Congress passed a resolution in 1964 declaring it so.) In fact, although people began to use the term “bourbon” in reference to a whiskey made mainly from corn, bourbon wasn’t really even a thing until around the 1870s. So Professor Thomas wasn’t as sacrilegious in omitting bourbon from his julep recipe as it seems at first glance.

Yet rye whiskey was a thing and had been so since the late 1700s. A very big thing. No less a figure than George Washington opened the nation’s biggest rye whiskey distillery in Mount Vernon after his tenure as President ended, to capitalize on rye’s popularity.

So why did Professor Thomas opt for Cognac in his original Georgia Mint Julep recipe, rather than a spirit developed closer to home?

In a word: audience. Thomas was writing a book on cocktails, a relatively recent invention for a rather upscale clientele who could afford both the showmanship of mixology and the spirits included in the final product of such theatrics.

In the mid-1800s, whiskey didn’t exactly have a reputation for quality — Scotch was especially haunted by poor reviews after many Scottish distillers had abandoned their pot stills in favor of the more efficient column still. France still had a firm grip on luxury culture of the day, especially its world-renowned wine and distilled spirits, including Armagnac, Cognac, and Calvados. Of all the spirits, Cognac received the most acclaim.

Since the 1400s, Dutch traders importing French wines had concentrated French wine into distilled spirits form and stored it in oak casks for the rough voyage from the southern France to Amsterdam. Once at port, the traders would add water to this distilled wine (or “brandewijn” — burnt wine in Dutch) to reconstitute the wine spirit into wine.

French vineyard owners took note. As taxes on wine increased, they diverted some of their plantings to more acidic grapes, most notably the Folle Blanche varietal. The growers and Cognac producers built long houses called chais along the Charente River to store French oak casks of newly double-distilled Cognac. (Whisk(e)y was late to the game, only beginning to receive barrel treatment in the mid-1800s.)

French distillers’ Cognac matured in these damp riverside conditions slowly over a number of years, driving up the price of Cognac with each passing day. Such lengthy maturation conditions, along with the finesse and complexity of the cask-aged Cognac and lack of high-end alternatives gave Cognac’s elevation to luxury status an air of inevitability.

The rich and famous on the U.S.’ eastern seaboard joined in the fun, quaffing Cognac at galas year-round. Honest Abe drank it, albeit in small amounts. President Chester A. Arthur downed it (and its teetotal cousin, wine) two decades later.

Conspicuous consumption had never gotten such a rush of rancio to the head.

But in 1872, something mysterious began to happen. Grapevines in France inexplicably died. No one knew why. Vintners labeled it “wine fretters”, and fretting they did. Scientists soon discovered the plague was a tiny, yellow insect related to the aphid — they named it Phylloxera vitifoliae. (That part of the species name rhymed with pox seems most fitting.)

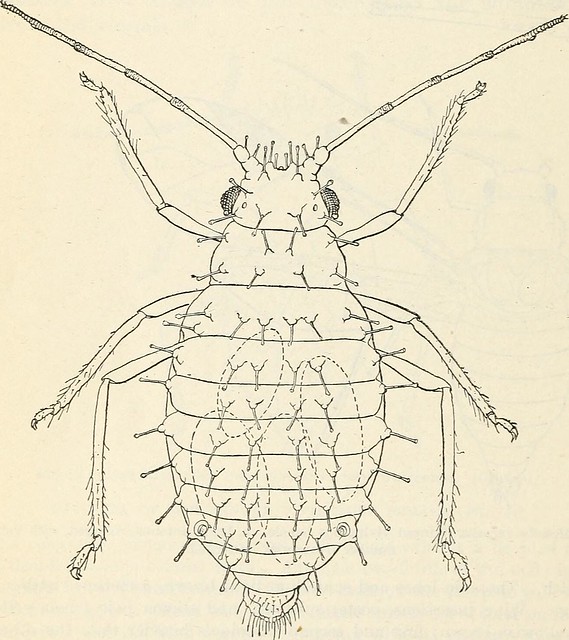

Phylloxera's cousin, the aphid.

The supply of French wine and Cognac plummeted throughout the rest of the century. Cognac-makers ripped up the old Folle Blanche vines and planted a new, Phylloxera-resistant varietal, St. Emilion. But Cognac would never recover its prowess as the luxury tipple of choice.

Whisk(e)y, especially Scotch, rose to the occasion, filling the luxury drinks void that Phylloxera had left. Even during the World Wars when millions of soldiers from around the globe crossed French soil, whisk(e)y retained its edge. An edge it maintains to this day.

The irony of the whole epidemic is that the insect only found its way to European shores when British scientists brought cuttings from U.S. vines to the United Kingdom for study. Hard to believe that a careless, cross-Atlantic transplanting of grapes led to a century-plus depression for Cognac.

But things are looking up for Cognac and the brandy category in general. (Cognac is a sub-category of brandy — which is a distilled spirit made from fruit, usually grapes.) After declines in the years leading up to 2015, Cognac sales finally rose at a fast clip last year. Many U.S. journalists have begun speculating on whether U.S. apple brandy may likewise begin an ascent. (President Reagan served the most famous U.S. brandy — Germain-Robin — to President Gorbachev during their many visits.)

These are welcome signs of vitality from a quality category that has received neglect for too long. As the Union troops proved a century and a half ago, a few down years don’t always spell doom. Professor Thomas would likely agree. We certainly do.

— — — — —

(1) The aggressive recipe also calls for 1.5oz of peach brandy.

"It's not spelled with an e." A brief history of the whisky vs. whiskey debate

One rather balmy December day nearly eight years ago, celebrated New York Times author Eric Asimov published an in-depth piece comparing a number of 12 year old Speyside Scotches. Within hours, single malt enthusiasts the world over had left him angry messages.

Was it because he’d rated The Glenlivet above Macallan? Or had he perhaps done the unthinkable and added ice to the tasting?

Neither, it turns out.

One rather balmy December day nearly eight years ago, celebrated New York Times author Eric Asimov published an in-depth piece comparing a number of 12 year old Speyside Scotches. Within hours, single malt enthusiasts the world over had left him angry messages.

Was it because he’d rated The Glenlivet above Macallan? Or had he perhaps done the unthinkable and added ice to the tasting?

Neither, it turns out.

Rather, he’d scattered the offensive letter “e” all about his article in the worst of places — between the “k” and the “y” in the word whisky. One commentator even found Asimov’s use of “whiskey” to make the “article quite unreadable,” a faux pas that “a reputable writer should not make.”

The source of the outcry is not simply a case of lexical whimsy. The genesis of these Scotch enthusiasts’ anger dates back centuries, highlighting rivalries between the British Isles second and third most populous countries.

Some claim that the linguistic rift began when frugal Scottish printers found they could save money by shedding vowels from words like a sinking boat jettisoning anvils.(1)

Others claim that the spelling divergence arose in the 1870s, when Irish distillers sought to distinguish their spirit from the Scottish swill that had flooded the market after the advent of the Coffey still.

The type of still that once ruled Scotch.

Regardless of the source of the rift, the difference in spelling is not merely an exercise in academic nerdery. Both the Scottish and the Irish seem to find — bound up within the spelling — a symbol of their culture; as one critic of Mr. Asimov summed up in asserting the use of “whiskey” in reference to Scotch: it’s “an embarrassing solecism unworthy of the New York Times.”

This makes sense. The Scottish and Irish have a centuries-old, somewhat friendly rivalry (2)— the type of rivalry that claims sports and spirits as its main sticking points. Adding fuel to this rivalry, Scotland likely pilfered the concept of whisk(e)y — or uisge baugh, as the Irish called it — then proceeded to become the dominant exporter of the spirit worldwide, while Ireland’s whiskey industry struggled through multiple internecine and international wars, along with U.S. Prohibition.

If the difference in usage stopped with just Ireland and Scotland, there wouldn’t be much to worry about. Just like the “i before e, but not after c” rule, we’d memorize it and be done.

But bright line rules are for managers and mathematicians, not whiskey-makers. A world without complexity wouldn’t need whiskey in the first place. So to complicate matters, since the original linguistic split between Ireland and Scotland centuries ago, the U.S. has for the most part adopted the Irish spelling, while Canada and Japan have opted for the Scottish spelling.(3)

A world without complexity wouldn’t need whiskey in the first place.

Newer distilleries opening as far afield as India and Australia often choose the Scottish spelling as well, likely due to the reputation for quality that Scottish distillers have given to the term “Scotch whisky” in the past few decades. Even a few distilleries in the U.S. elect to use the Scottish spelling — Maker’s Mark chief among them — which likely stem from the companies’ Scottish heritage.

But not all newcomer distilleries prefer the Scottish spelling. Take for example, Mexico’s Dorwart Whiskey, which prints “Whiskey” prominently on the front of each bottle.

Dorwart’s market entry confounds the catchy rule that many whisk(e)y writers had developed through the years to remember which spelling goes with which country. The rule went something like this: if the country has an “e” — namely, Ireland and the United States — its spelling of whiskey does, too; if the country lacks an “e” — namely, Scotland, Canada, and Japan — its spelling of whisky does, too.

Nowadays, perhaps the easiest rule to remember, if you’re into accuracy, is that the place that made whiskey first (Ireland), the place that made whiskey most recently (Mexico), and the place that makes whiskey the best (United States) all use the “e”.(4) Everyone else sheds the "e".

When referring to the spirit generally, you can refer to it as whiskey with the "e", as is the custom here in the US. But if you come within ten characters of the word Scotch, you'd be well-advised to drop the "e" like the Dodgers dropped Brooklyn almost a half-century ago. Even the New York Times Monsieur Asimov might agree.

— — — — —

(1) To which the Scottish retort: “It only takes us two distillations to get it right” — a direct jab at the traditional Irish method of triple distillation.

(2) Some Irish don’t necessarily view it as quite so friendly.

(3) Japan’s use of “whisky” makes sense, as the godfather of Japanese whisky, Masataka Taketsuru, trained at the now-defunct Hazelburn Distillery on Scotland’s Kintyre Peninsula. Canada’s adoption of “whisky” may reflect its historic ties with the Crown.

(4) We jest. In addition to distilleries in the US, distilleries in Japan, Scotland, and Taiwan all bottle some of our favorite drams of all time.