CRAFTED WITH CHARACTERS

A collection of our thoughts on whiskey, spirits

&

the world

Fiddler Bourbon

With more than double the wheat content of other “wheated” bourbons, Fiddler’s distinctive grain bill makes it one of the most unique bourbons on the market. A perfect combination of corn, wheat and barley unite to create a smooth, soft bourbon that can be enjoyed by both the whiskey novice and enthusiast. Fiddler started its journey in new 53 gallon barrels and is then finished in-house using an assortment of methods, more specifically described on the label of each release. Releases include Fiddler Original (Release 1; finished in 15-gallon quarter casks), Fiddler Georgia Heartwood (Releases 2-5 and Release 7; finished with staves of white oak heartwood that we harvested in Jackson County, Georgia, seasoned for over a year, and hand-charred), Fiddler Wheated Straight Bourbon Whiskey (Release 6; Atlanta’s first straight bourbon since Prohibition), and Fiddler Unison (Release 8-present; blended with our own in-house bourbon stocks that we distilled on our traditional, Scottish-style copper pot stills with corn from Ranger, Georgia’s Riverview Farms).

In addition to the double-copper-pot-distilled bourbon, rye & malt whiskies, plus seasonal fruit brandies using local Georgia produce that ASW Distillery produces in-house, the ASW team created Fiddler as a line to showcase interesting and difficult to obtain whiskey from across the country and eventually around the world.

FIDDLER BOURBON

Our line of unique, award-winning Bourbon Whiskies, named as a nod to our Master Distiller, Justin Manglitz, an accomplished fiddler, and including:

A smooth, easy-drinking high-wheat bourbon (Fiddler Unison Bourbon)

A robust high-malt, pot-distilled bourbon (Fiddler Soloist Straight Bourbon)

A cask strength bourbon that we finish on staves of oak (Fiddler Georgia Heartwood Bourbon).

Together, they’re the perfect Backyard Bourbon.

More about those 3 expressions of Fiddler Bourbon:

Fiddler Unison Bourbon: A true ode to American Bourbon, perfect for campfires, concerts, and a killer Old Fashioned, Fiddler Unison Bourbon is a marriage of a foraged, wheated bourbon & our house-distilled high-malt bourbon. 90 proof, available year-round.

Fiddler Georgia Heartwood Bourbon: The same foraged high-wheat bourbon as our flagship Fiddler Unison, finished on staves of Georgia oak that our distilling team harvested and hand-charred. The 45% wheat content is unique for bourbons, leading to a sweet, smooth profile, despite its high proof.. Cask Strength, only available at a handful of accounts who have selected a barrel

Fiddler Soloist Straight Bourbon: The First Straight Bourbon Ever Distilled in The City of Atlanta*, Fiddler Soloist is a unique take on America's native spirit, reducing the corn in favor of flavorful malts and distilled on our copper pot stills with the grains in. *Straight Bourbon did not become a defined term under American law until 1907, two years after the State of Georgia instituted statewide prohibition that didn’t lift until 1935 – for a much longer statewide prohibition period than federal Prohibition.

Tasting notes:

Fiddler Unison Bourbon: Caramel, citrus, green apple, nutmeg

Fiddler Georgia Heartwood Bourbon: Baking spice, maple syrup, oak, toffee

Fiddler Soloist Straight Bourbon: Cherry cola, chocolate, Cinnamon Toast Crunch, peanut brittle

Awards:

Fiddler Unison Bourbon: Silver Medal, San Francisco World Spirits Competition, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018

Fiddler Georgia Heartwood Bourbon: Gold Medal, San Francisco World Spirits Competition, 2021, 2018

Fiddler Soloist Straight Bourbon: Gold Medal, San Francisco World Spirits Competition, 2020

Locate Fiddler Bourbon near you at our map below.

Interested in learning more?

Visit any of our 3 Atlanta tasting rooms and spirits manufacturing facilities:

ASW Distillery (Buckhead) where we distill our whiskies

ASW Whiskey Exchange (West End) where we age our whiskies

ASW at The Battery Atlanta (near the Atlanta Braves stadium) where we distill our vodka and gin

The Most Awarded Craft Whiskey Distillery since 2018

The awards above, combined with our other whiskies’ medals, have made us the Most Awarded Craft Whiskey Distillery since 2018 at the prestigious San Francisco World Spirits Competition. Medals during that time span include 6 Double Gold Medals, 6 Gold Medals, numerous Silver Medals, and 2020’s Craft Whiskey of the Year, Maris Otter Single Malt (Cask Strength edition).

Winterville Gin

With more than double the wheat content of other “wheated” bourbons, Fiddler’s distinctive grain bill makes it one of the most unique bourbons on the market. A perfect combination of corn, wheat and barley unite to create a smooth, soft bourbon that can be enjoyed by both the whiskey novice and enthusiast. Fiddler started its journey in new 53 gallon barrels and is then finished in-house using an assortment of methods, more specifically described on the label of each release. Releases include Fiddler Original (Release 1; finished in 15-gallon quarter casks), Fiddler Georgia Heartwood (Releases 2-5 and Release 7; finished with staves of white oak heartwood that we harvested in Jackson County, Georgia, seasoned for over a year, and hand-charred), Fiddler Wheated Straight Bourbon Whiskey (Release 6; Atlanta’s first straight bourbon since Prohibition), and Fiddler Unison (Release 8-present; blended with our own in-house bourbon stocks that we distilled on our traditional, Scottish-style copper pot stills with corn from Ranger, Georgia’s Riverview Farms).

In addition to the double-copper-pot-distilled bourbon, rye & malt whiskies, plus seasonal fruit brandies using local Georgia produce that ASW Distillery produces in-house, the ASW team created Fiddler as a line to showcase interesting and difficult to obtain whiskey from across the country and eventually around the world.

WINTERVILLE GIN

Distilled from thirteen botanicals, Winterville Gin tones down the juniper in traditional dry gins in favor of citrus and floral notes, including marigold, a flower celebrated at Winterville, Georgia's annual Marigold Festival. Winterville is known for its slow pace and friendly disposition.

R&D began with over 40 botanical extractions from, then experimenting with various combinations to build 10 different recipes that our team tasted. Recipe No. 6 proved to be the unanimous choice. The final step was deciding on the proof: Of all 4 proofs we tried, 95 proof was the unanimous favorite, making Winterville a great choice for classic gin cocktails like the Gin & Tonic, Aviation and Negroni.

Tasting notes: Citrus, coriander, floral, juniper, marigold

Locate Winterville Gin near you at our map below.

Interested in learning more?

Visit any of our 3 Atlanta tasting rooms and spirits manufacturing facilities:

ASW Distillery (Buckhead) where we distill our whiskies

ASW Whiskey Exchange (West End) where we age our whiskies

ASW at The Battery Atlanta (near the Atlanta Braves stadium) where we distill our vodka and gin

Bustletown Vodka

With more than double the wheat content of other “wheated” bourbons, Fiddler’s distinctive grain bill makes it one of the most unique bourbons on the market. A perfect combination of corn, wheat and barley unite to create a smooth, soft bourbon that can be enjoyed by both the whiskey novice and enthusiast. Fiddler started its journey in new 53 gallon barrels and is then finished in-house using an assortment of methods, more specifically described on the label of each release. Releases include Fiddler Original (Release 1; finished in 15-gallon quarter casks), Fiddler Georgia Heartwood (Releases 2-5 and Release 7; finished with staves of white oak heartwood that we harvested in Jackson County, Georgia, seasoned for over a year, and hand-charred), Fiddler Wheated Straight Bourbon Whiskey (Release 6; Atlanta’s first straight bourbon since Prohibition), and Fiddler Unison (Release 8-present; blended with our own in-house bourbon stocks that we distilled on our traditional, Scottish-style copper pot stills with corn from Ranger, Georgia’s Riverview Farms).

In addition to the double-copper-pot-distilled bourbon, rye & malt whiskies, plus seasonal fruit brandies using local Georgia produce that ASW Distillery produces in-house, the ASW team created Fiddler as a line to showcase interesting and difficult to obtain whiskey from across the country and eventually around the world.

BUSTLETOWN VODKA

Named after the hustle and bustle of the Busiest City in the South, Bustletown is seven-times distilled and drinks smooth as a cloud.

After years of establishing a reputation for quality making whiskey, we introduced Bustletown Vodka by popular demand. The first spirit distilled at our ASW at The Battery Atlanta location, right next to the Atlanta Braves stadium, Bustletown is seven-times distilled from 100% grain in small batches using only choice cuts, then ultra-filtered through activated charcoal for as smooth, refined, and pure a vodka as you’ll find. The sleek label takes its cue from Atlanta being the site of the busiest airport in the world

Tasting notes: Creamy, slightly sweet, subtle black pepper

Awards: 91 Points, International Wine & Spirits Competition, 2021

Locate Bustletown Vodka near you at our map below.

Interested in learning more?

Visit any of our 3 Atlanta tasting rooms and spirits manufacturing facilities:

ASW Distillery (Buckhead) where we distill our whiskies

ASW Whiskey Exchange (West End) where we age our whiskies

ASW at The Battery Atlanta (near the Atlanta Braves stadium) where we distill our vodka and gin

Resurgens Rye

In distilling Atlanta's first rye since Prohibition on its traditional, Scottish-style twin copper pot stills, we took our cue from Atlanta's vibrant craft brewing community to explore new, unique whiskey styles largely ignored by large distilleries. Rye is one of Georgia's traditional grains, and we feature it front and center in Resurgens, crafting Resurgens Rye from 100% malted rye, to create a flavorful whiskey that showcases rye’s potential. We at ASW Distillery aged Resurgens Rye in new, charred American white oak casks, balancing the dryness of the rye with sweetness from the barrel to create an exceptional whiskey, unique to Atlanta. We also release a Port-Cask-Finished expression of Resurgens once per year.

Rye was long-forgotten after the end of Prohibition, but has recently seen a renaissance. Resurgens is ASW Distillery's own take on this expanding category. It's only fitting that renowned Athens artist David Hale - a direct blood descendant of Basil Hayden, the first person to introduce rye into bourbon recipes - crafted the Resurgens Rye label art.

Resurgens Rye

A revival of the Appalachian-style Ryes of yore, we distill Resurgens from 100% malted rye (rather than the unmalted rye of most ryes). Sweeter & more chocolate-forward than a traditional rye, it maintains the stone fruit and spice you’d expect.

Use the map at the bottom of this page to find it.

In distilling Atlanta's first rye since Prohibition on its traditional, Scottish-style twin copper pot stills, we took our cue from Atlanta's vibrant craft brewing community to explore new, unique whiskey styles largely ignored by large distilleries. Rye is one of Georgia's traditional grains, and we feature it front and center in Resurgens, crafting Resurgens Rye from 100% malted rye, to create a flavorful whiskey that showcases rye’s potential. We at ASW Distillery aged Resurgens Rye in new, charred American white oak casks, balancing the dryness of the rye with sweetness from the barrel to create an exceptional whiskey, unique to Atlanta. We also release a Port-Cask-Finished expression of Resurgens once per year.

Rye was long-forgotten after the end of Prohibition, but has recently seen a renaissance. Resurgens is ASW Distillery's own take on this expanding category. It's only fitting that renowned Athens artist David Hale - a direct blood descendant of Basil Hayden, the first person to introduce rye into bourbon recipes - crafted the Resurgens Rye label art.

Tasting notes: Chocolate, graham cracker, apricot

Awards: Double Gold Medal, San Francisco World Spirits Competition, 2020

Locate Resurgens Rye near you at our map here:

Interested in learning more?

Visit any of our 3 Atlanta tasting rooms and spirits manufacturing facilities:

ASW Distillery (Buckhead) where we distill our whiskies

ASW Whiskey Exchange (West End) where we age our whiskies

ASW at The Battery Atlanta (near the Atlanta Braves stadium) where we distill our vodka and gin

The Most Awarded Craft Whiskey Distillery since 2018

The awards above, combined with our other whiskies’ medals, have made us the Most Awarded Craft Whiskey Distillery since 2018 at the prestigious San Francisco World Spirits Competition. Medals during that time span include 6 Double Gold Medals, 6 Gold Medals, numerous Silver Medals, and 2020’s Craft Whiskey of the Year, Maris Otter Single Malt (Cask Strength edition).

Duality Double Malt

Duality Double Malt is the World's 1st Whiskey of Its Kind, a delicious whiskey that sips like the crossroads of a smoky single malt and a robust rye.

Duality Double Malt was a happy accident, an experiment gone right when the grain supplier for our Head Distiller, Justin Manglitz, didn't have enough malted rye for Justin to make a full batch of Resurgens Rye. Justin exercised his ingenuity and added malted barley into the batch. As he normally did with Resurgens, Justin retained the grain-solids of both grains throughout the whole production process (from mashing, to fermentation, to distillation).

We expanded on the dual themes by finishing Duality in a combination of new & used barrels and bottling it at 88 proof. The result in Duality Double Malt is something truly unique, a testament to the innovative flavor combinations that craft distilleries across the U.S. are pioneering.

The label features a number of dualistic Easter eggs, including a Scottish-Gaelic translation of the first verses in Act V, Scene I of MacBeth: "Double double, toil and trouble, fire burn, and cauldron bubble."

DUALITY DOUBLE MALT WHISKEY

A delicious symphony of rye and cherry-smoked malted barley, for the World's 1st Double Malt and Georgia's 1st Ever Double Gold Whiskey. It was a "happy accident" or "experiment gone right", depending on who you ask.

Use the map at the bottom of this page to find it.

Duality Double Malt is the World's 1st Whiskey of Its Kind, a delicious whiskey that sips like the crossroads of a smoky single malt and a robust rye.

Duality Double Malt was a happy accident, an experiment gone right when the grain supplier for our Head Distiller, Justin Manglitz, didn't have enough malted rye for Justin to make a full batch of Resurgens Rye. Justin exercised his ingenuity and added malted barley into the batch. As he normally did with Resurgens, Justin retained the grain-solids of both grains throughout the whole production process (from mashing, to fermentation, to distillation).

We expanded on the dual themes by finishing Duality in a combination of new & used barrels and bottling it at 88 proof. The result in Duality Double Malt is something truly unique, a testament to the innovative flavor combinations that craft distilleries across the U.S. are pioneering.

The label features a number of dualistic Easter eggs, including a Scottish-Gaelic translation of the first verses in Act V, Scene I of MacBeth: "Double double, toil and trouble, fire burn, and cauldron bubble."

Tasting Notes: Cedar, coffee, cranberry, smoke, toffee

Awards: Double Gold Medal, 2018, San Francisco World Spirits Competition

Locate Duality Double Malt near you at our account map:

Interested in learning more?

Visit any of our 3 Atlanta tasting rooms and spirits manufacturing facilities:

ASW Distillery (Buckhead) where we distill our whiskies

ASW Whiskey Exchange (West End) where we age our whiskies

ASW at The Battery Atlanta (near the Atlanta Braves stadium) where we distill our vodka and gin

The Most Awarded Craft Whiskey Distillery since 2018

The awards above, combined with our other whiskies’ medals, have made us the Most Awarded Craft Whiskey Distillery since 2018 at the prestigious San Francisco World Spirits Competition. Medals during that time span include 6 Double Gold Medals, 6 Gold Medals, numerous Silver Medals, and 2020’s Craft Whiskey of the Year, Maris Otter Single Malt (Cask Strength edition).

Druid Hill Irish-Style Whiskey

We've crafted Druid Hill in the old Irish tradition with 30% unmalted barley (an innovation originally developed to avoid taxes on malt) and 70% malted barley grown by Loughran's Malt, a 6th Generation family farm in County Louth, Ireland, at the foot of the Cooley Mountains near Dublin.

Just a stone's throw from our distillery, amid the Piedmont's oak-studded slopes, lies Druid Hills, an idyllic area from whence this whiskey takes its name, a nod to the decades that the Druids of Celtic Ireland and our Head Distiller both spent mastering the ancient art of whiskey-making.

Druid Hill Irish-Style Whiskey

A delicious, Irish-style whiskey, triple-distilled from a combination of malted and unmalted barley grown by a 6th Generation family farm in County Louth, Ireland.

Use the map at the bottom of this page to find it.

We've crafted Druid Hill in the old Irish tradition with 30% unmalted barley (an innovation originally developed to avoid taxes on malt) and 70% malted barley grown by Loughran's Malt, a 6th Generation family farm in County Louth, Ireland, at the foot of the Cooley Mountains near Dublin.

Just a stone's throw from our distillery, amid the Piedmont's oak-studded slopes, lies Druid Hills, an idyllic area from whence this whiskey takes its name, a nod to the decades that the Druids of Celtic Ireland and our Head Distiller both spent mastering the ancient art of whiskey-making.

Tasting Notes: Chocolate chip cookie dough, fig preserves, honey.

Awards: Double Gold Medal, San Francisco World Spirits Competition, 2021.

Locate Druid Hill Irish-Style Whiskey near you at our map here:

Interested in learning more?

Visit any of our 3 Atlanta tasting rooms and spirits manufacturing facilities:

ASW Distillery (Buckhead) where we distill our whiskies

ASW Whiskey Exchange (West End) where we age our whiskies

ASW at The Battery Atlanta (near the Atlanta Braves stadium) where we distill our vodka and gin

The Most Awarded Craft Whiskey Distillery since 2018

The awards above, combined with our other whiskies’ medals, have made us the Most Awarded Craft Whiskey Distillery since 2018 at the prestigious San Francisco World Spirits Competition. Medals during that time span include 6 Double Gold Medals, 6 Gold Medals, numerous Silver Medals, and 2020’s Craft Whiskey of the Year, Maris Otter Single Malt (Cask Strength edition).

Tire Fire Heavily Peated Single Malt

With a nose that’s a bouquet of barbecue, a palate that whisks you to salt-sprayed islands in the far north, and a finish that — like the Northwest Passage — lasts a brief eternity, Tire Fire is for those who share their breakfast with bears.

Our Head Distiller Justin Manglitz got his start perfecting his booze-making techniques over 18 years ago. Though he'd always loved Irish Pure Pot Still Whiskies and Lightly Peated Single Malt Scotches (like the bottle of Macallan he received for graduation), he'd always found heavily peated single malts to taste like burning rubber. So when the rest of the team here — who love our Islay-style single malt whiskies — put Justin up to the task of distilling a peat bomb he'd actually drink, he gladly accepted the challenge.

If you like your whiskey with all the peat that can be seared into a single dram, we think this will suit you just fine. Largely because it’s peaty, and delicious.

Tire Fire Heavily Peated Single Malt Whiskey

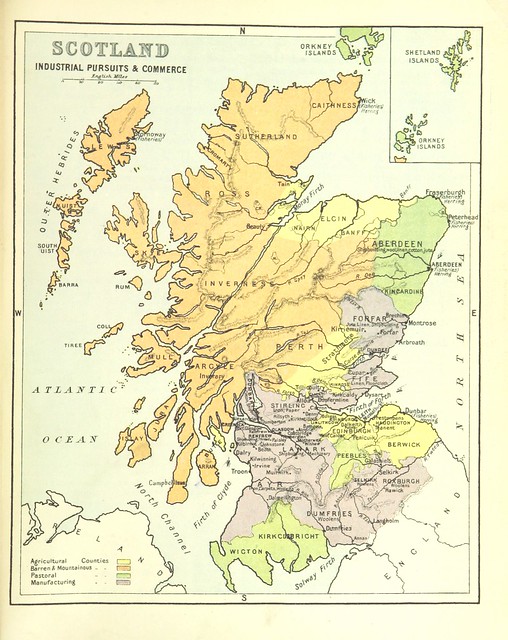

A delicious, Islay-style single malt whiskey, distilled on our Scottish-style twin copper pot stills from 100% peated barley from Inverness, Scotland.

Use the map at the bottom of this page to find it.

With a nose that’s a bouquet of barbecue, a palate that whisks you to salt-sprayed islands in the far north, and a finish that — like the Northwest Passage — lasts a brief eternity, Tire Fire is for those who share their breakfast with bears.

Our Head Distiller Justin Manglitz got his start perfecting his booze-making techniques over 18 years ago. Though he'd always loved Irish Pure Pot Still Whiskies and Lightly Peated Single Malt Scotches (like the bottle of Macallan he received for graduation), he'd always found heavily peated single malts to taste like burning rubber. So when the rest of the team here — who love our Islay-style single malt whiskies — put Justin up to the task of distilling a peat bomb he'd actually drink, he gladly accepted the challenge.

If you like your whiskey with all the peat that can be seared into a single dram, we think this will suit you just fine. Largely because it’s peaty, and delicious.

Tasting Notes: Brown sugar, peat, cherry, vanilla ice cream.

Awards: Gold Medal, San Francisco World Spirits Competition, 2021 (Cask Strength); Gold Medal, San Francisco World Spirits Competition, 2020 (91 Proof).

Locate Tire Fire Heavily Peated Single Malt near you at our map here:

Interested in learning more?

Visit any of our 3 Atlanta tasting rooms and spirits manufacturing facilities:

ASW Distillery (Buckhead) where we distill our whiskies

ASW Whiskey Exchange (West End) where we age our whiskies

ASW at The Battery Atlanta (near the Atlanta Braves stadium) where we distill our vodka and gin

The Most Awarded Craft Whiskey Distillery since 2018

The awards above, combined with our other whiskies’ medals, have made us the Most Awarded Craft Whiskey Distillery since 2018 at the prestigious San Francisco World Spirits Competition. Medals during that time span include 6 Double Gold Medals, 6 Gold Medals, numerous Silver Medals, and 2020’s Craft Whiskey of the Year, Maris Otter Single Malt (Cask Strength edition).

Tips for Visiting Atlanta

Here at ASW Distillery, we love all that Atlanta has to offer, the diverse neighborhoods, world-class restaurants, vibrant nightlife, and thriving cultural scene. If you’re heading to The City Too Busy to Hate any time soon, we hope you’ll consider stopping by either of our locations: the Distillery or the Barrel Exchange. To that end, we’ve put together these 5 tips to help you plan for your visit.

#1 Best Time to Visit

Atlanta is known for its hot and humid summers, with temperatures at their highest in July and August. We recommend visiting Atlanta between March to May when temperatures are milder and you can enjoy outdoor activities, festivals, and concerts. In the spring, Atlanta is truly beautiful with the azaleas and dogwoods in full bloom.

#2 Airport Travel Tips

Hartsfield-Jackson Airport (ATL) is the world’s busiest passenger airport. Seven large concourses are connected via a subway and miles of moving walkways. This means that it can take a significant time to get to your gate, so plan to arrive at least two hours in advance (even more for international flights). Save time at the airport by booking your ATL parking in advance so that you have a parking spot waiting for you when you arrive.

#3 Getting Around

The road congestion in Atlanta can make it difficult to get around. The good thing is that you don’t need a car to get around Atlanta. The extensive public transportation system is called MARTA and it connects the major parts of the city and nearby suburbs. The fare is reasonable and you can purchase a day or weekly pass if you know you will be hopping on and off throughout your visit.

#4 Where to Stay

There are a number of trendy neighborhoods around Atlanta and each has its own distinctive character. Little Five Points is known for its great dive bars, vegan restaurants, and music scene. East Atlanta Village boasts tons of local restaurants, independent bookshops, artisan bakeries, and a vibrant arts and music scene. The historic West End neighborhood is known for its terrific soul food restaurants, the Westside BeltLine, and the ASW Whiskey Exchange. You can also stay Downtown or in Midtown if you want to be near the main tourist attractions.

#5 What to Do

Downtown Atlanta is home to four major attractions: The Georgia Aquarium, World of Coca-Cola, The CNN Center, and the National Center for Civil and Human Rights. If you want a real taste of Atlanta, then spend time on Auburn Avenue, where you will find the birth home of Dr. Martin Luther King, the Ebenezer Baptist Church, and The King Center. Catch a Braves baseball game, Falcons football game, or Hawks basketball game. Take a tour and experience our tasting room at the ASW Whiskey Exchange. We hope to see you soon!

5 Whiskey Recipes That Will Blow Your Mind

The world of whiskey is an endless ocean of variation, taste and competition. Every year, craft distillers across the country make use of their creative talents and skill to create the best whiskey available on the market. They achieve this by using a variety of ingredients, mash recipes, distillation equipment, distilling methods, and barrel aging techniques. Each new batch is an art form as well as a science to create something truly splendid.

This guest post comes to us from Kyle Doran, of Mile Hi Distilling equipment.

The world of whiskey is an endless ocean of variation, taste and competition. Every year, craft distillers across the country make use of their creative talents and skill to create the best whiskey available on the market. They achieve this by using a variety of ingredients, mash recipes, distillation equipment, distilling methods, and barrel aging techniques. Each new batch is an art form as well as a science to create something truly splendid.

Celebrated cocktails take note of these exquisite whiskeys and aim to augment their flavor profiles within their recipes. Below, we've outlined a few delicious cocktail ideas, along with some of the most praiseworthy whiskeys available today. Let's dive in.

Resurgens Rye

Created by ASW Distillery (that's us!), Resurgens Rye has a very unique take on Rye whiskey. For the mash recipe, ASW uses 100% malted rye, including nearly 5% chocolate malted rye. They use malted rye (rather than the unmalted rye of most ryes on the market) in the mash. This allows for a more concentrated flavor profile of the rye itself to come through in the whiskey.

Resurgens Rye is distilled by a grain-in distillation technique, using Scottish-style double copper pot stills. The batches are then aged using an array of American white oak casks.

With hints of chocolate and sweet honey, Resurgens Rye is a perfect whiskey for making an Old Fashioned. Mix 1/2 teaspoon of sugar with a few dashes of water into a rocks glass. Add 3 dashes of Angostura Bitters. Muddle until dissolved. Add large ice cube to the glass. Pour 2 oz. of Resurgens Rye Whiskey. Stir and garnish with an orange slice.

Leopold Bros. Maryland-Style Rye Whiskey

Created by Leopold Bros. Distillery, Maryland-Style Rye Whiskey has a fruity and floral taste profile that is much less aggressive than other traditional American rye whiskeys. This is because they use a different type of rye and mash bill. In the 1800’s, two types of rye were primarily used to create mash for whiskeys. Pennsylvania Rye, and Maryland Rye.

The difference between these two ryes? Pennsylvania Rye has a nearly pure rye mash bill, which will produce a very dry and spicy whiskey. Maryland Rye, on the other hand, is made up with a 65% rye mash bill. It produces a much softer tasting whiskey with subtler spices and smoother flavors.

Leopold Bros. Maryland-Style Rye Whiskey's mash bill is around 65% rye, 15% corn, and 20% malted barley. The mash undergoes a bacterial fermentation in the distillery's cypress open fermenters. The acetic acid bacteria gives the mash its fruity flavors and aromas before the distillation phase. After distilling, it's then aged for 4 years in charred American oak barrels at 98 proof to produce an 86 proof end result.

For an alternative but delightful take on rye whiskey, give Leopold Bros. Maryland-Style Rye Whiskey a try. It's also great for making a Whiskey Smash. The light fruity hints of caramel and vanilla, mix well with mint leaves and lemon to create a refreshing cocktail. Place 5-7 mint leaves, a wedge of lemon and 1 tablespoon of sugar into a shaker. Muddle until the sugar has dissolved and the mint leaves and lemon are sufficiently ground. Pour 2 oz. of Leopold Bros. Maryland-Style Rye Whiskey. Shake, double-strain and pour into a rocks glass over 1 large ice cube.

Distillery 291's Single Barrel Colorado Rye Whiskey

Distillery 291's Single Barrel Colorado Rye Whiskey is a very notable whiskey this year. It was awarded the world's best Rye of 2018 by World Whiskies Awards. Its mash bill is composed of 61% malted rye and 39% corn resulting in a sweetness on the nose, spiciness on the palate and ending with a sweet finish. Finally, Single Barrel Colorado Rye Whiskey is aged for one year in American white oak barrels and then finished with charred aspen barrels. Michael Myers is the owner and head distiller at Distillery 291, which is located in Colorado Springs. His aim is to create whiskeys that reproduce the taste, smell and folklore of the Wild West.

With a flavor profile that includes cinnamon, oak and maple, the Vieux Carre is a great cocktail to create with Distillery 291's Colorado Rye Single Barrel Bourbon. Pour 3/4 oz. of bourbon, 3/4 oz. of Cognac, and 3/4 oz. of Vermouth into a mixing glass. Add 1 teaspoon of Bénédictine liqueur. Add 1 dash of each Peychaud’s Bitters and Angostura bitters. Fill mixing glass half full with ice. Stir until chilled and pour into chilled rocks glass.

Duality Double Malt

Another amazing spirit distilled by ASW Distillery, Duality Double Malt is the world's first whiskey of its kind because of its unique mash bill, distillation process and aging methods. The mash bill is made up of 50% cherry-smoked barley malt and 50% rye malt. Both of these malted grains are fermented together in the same vessel before the distilling process. The grains are left in during the first distillation which is done using the same Scottish tradition of double copper pot distilling that is used for Resurgens Rye. After distilling, the batch is aged in charred oak casks of varying sizes. As a result, this whiskey has a rich and complex flavor profile with hints of coffee, toffee, fruit and honey. Duality took home the Double Gold in the San Francisco World Spirits Competition in 2018. Whoever the connoisseur, this whiskey is definitely worth your time.

The Rusty Nail (Rusty Bob) is a simple, yet delicious cocktail that is perfect if you're in the mood for a sweet and light experience. With the rich tastes of honey, caramel, chocolate, coffee, and other mouthwatering flavors, the Duality Double Malt blends very well with the sweet herbal honey notes of Drambuie. Pour 1 1/2 oz. of Duality Double Malt and 1/2 oz. of Drambuie into a rocks glass over ice. That's it. Enjoy this easily made cocktail to your heart's delight.

Ridgemont Reserve 1792 Single Barrel

Ridgemont Reserve 1792 Single Barrel Bourbon is distilled by Barton 1792, a distillery established in 1879 and located in Bardstown, Kentucky. 1792 Bourbon Distillery gets its name from commemorating the year that Kentucky became a state. The mash bill is 75% corn, 15% rye, and 10% barley. Because of the mash bill ingredients and being aged 8 years in new charred oak barrels, this bourbon has subtle hints of butterscotch, maple and light oak. With the heat of the high rye composition, mixed with hints of caramel throughout, this is a whiskey worth appreciating. The Ridgemont Reserve 1792 Single Barrel has also won the Double Gold award in the San Francisco World Spirits Competition this year.

The sweet vanilla undertones of Ridgemont Reserve 1792, mixed with muddled mint leaves makes for a perfect Mint Julep. Place 6-8 mint leaves with 1 teaspoon of sugar in a rock glass. Lightly muddle until the mint leaves have broken down. Pour 2 oz. of Ridgemont Reserve 1792 over the mix. Add crushed ice until glass is topped. Garnish the glass with 1 mint leaf. Enjoy!

Generation after generation, distillers pass down the time honored tradition and artform of creating whiskey. As a result, craft whiskey distilleries are always looking to the horizon to expand on what their forefathers built before them. Amazing whiskeys are created every year by experimenting with different ingredients and techniques. Whether you're a newcomer or a seasoned connoisseur of whiskey, you will be able to appreciate each of these batches for a variety of reasons. Try out these whiskeys and cocktails and decide what you appreciate about the spectrum of different flavor profiles you find. We hope you've enjoyed this breakdown of some of the best whiskeys and cocktail recipes to try out this year.

Kyle Doran is a Colorado local and writer for Mile Hi Distilling, a manufacturer of high quality whiskey and moonshine stills as well as other distilling products. Kyle is fascinated by the history of craft distilling, the distilling process and loves to discuss different varieties of spirits and liquors. His favorite spirits are bourbon, whiskey and moonshine.

Interested in a tour & tasting at our Atlanta distillery? That's great news! Book your tasting & tour below:

Three Variations on the 2nd Best Old Fashioned

Few cocktails have have captured the minds of the thirsty public or generated as much interest in the past two centuries as that old Bourbon standby, the Old Fashioned.

Few cocktails have have captured the minds of the thirsty public or generated as much interest in the past two centuries as that old Bourbon standby, the Old Fashioned.

The History of the Old Fashioned: Sazeracs to Martinis

Sure, the Martini had its heyday in those dark days when whiskey was merely an afterthought of the spirits-sipping population. Then there’s the Manhattan -- one of our unanimous favorite cocktails here at ASW Distillery -- named after perhaps the most famous city on earth.

And, of course, the alleged fountainhead of all cocktails, the Sazerac, hails from mid-1800s New Orleans, when a certain Sewell Taylor sold his bar to become an importer of the Sazerac-de-Forge et Fils brand of cognac that entrepreneur Aaron Bird (who bought Taylor’s bar) mixed into his “Sazerac Cocktail”. The cocktail just happened to include local bitters from Antoine Amedie Peychaud, the inventor of Peychaud’s. After an epidemic devastated French vineyards and drove up cognac prices, the Sazerac began to dress up the corn-and-rye-based swill floating down the Mississippi River instead. Like the Manhattan, the Sazerac is a favorite of ours at the distillery. In fact, we make a mean one as part of our cocktail program, which you can enjoy any Thursday, Friday, or Saturday during our tasting hours.

But since the Bourbon Old Fashioned’s formalization in Louisville, Kentucky, and subsequent popularization at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York, the Old Fashioned has been a go-to staple of everyone from creator of fictional lands, George Lucas, to fictional creator of ads, Don Draper in Mad Men, who consumed enough of them to send chills down Winston Churchill’s spine.

The word “cocktail” arose in the early 1800s, when an editor of New York’s The Balance and Columbian Repository defined the drink as a mixture of spirits, bitters, water, and sugar. But as the 1800s progressed from gas lamps to electric street lights, barkeeps had begun concocting cocktails with a wider array of modifiers -- everything from orange curaçao to absinthe (as in the case of the Sazerac). In the 1860s, tipplers began to long for the “good old days” of the cocktail, perhaps as a response to the psychological impact of the Civil War.

I'll Have It the 'Old Fashioned' Way

Soon, the “old fashioned” way of making cocktails came back into fashion, featuring just spirits, bitters, water, and sugar. A barkeep from Chicago mentioned that the most popular base spirit in the Old Fashioned of the 1870s was whiskey (albeit rye at the time, rather than bourbon). But the name “Old Fashioned” as a proper noun hadn’t yet entered the common vernacular. For that, we can credit Louisville, Kentucky’s gentleman’s club, the Pendennis Club, founded in 1881. A bartender in the city devised the delicious concoction to consist of lots of bourbon, a little water and sugar, and a hint of bitters and orange. James E. Pepper, a well-known whiskey distiller of the day, transported this newly named “Old Fashioned” cocktail to New York City’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, and the rest is history.

In 2015, Louisville even named the Old Fashioned as its City Cocktail, creating a two-week celebration of the drink in its annual “Old Fashioned Fortnight”. How many other boozy drinks can claim to be the cocktail representing an entire city?

But an Old Fashioned is more than just the spirited sum of sugar, water, bourbon, bitters, and a stale bar garnish like a desiccated orange peel or canned cherry. There is an art to the Old Fashioned that requires balance and imagination. To that end, we here at ASW Distillery have experimented with numerous variations on the Old Fashioned theme over the years, three of which we finally got to unveil to guests in 2017.

New GA Laws: Vetting Our Old Fashioned Recipes

How’s that? Well, when Georgia updated its distillery laws that took effect on September 1, 2017, the law finally permitted us as a distiller of spirits to serve cocktails directly to the public. We were suddenly transformed from distillery with a nice tasting room into a sort of cocktail bar (albeit with tighter hours) serving up delicious & inexpensive cocktails right across the street from SweetWater Brewery.

For our first cocktail menu, we included classics like a Southern Mule (made with bourbon and local bitters heroes, 1821 Bitters Ginger Beer), a Sazerac, and, of course, one of our Old Fashioned recipes.

The night of Sept. 1, when we unveiled the new cocktails, one patron paid us the weighty compliment: “That’s the 2nd best Old Fashioned I’ve ever had.” Thing was, he couldn't remember the first. So we assumed either it was a fine specimen of boozy goodness, or the patron was concerned with grade inflation.

In either event, the compliment tickled us better than Elmo, and ever since that fateful, ego-stroking evening, we’ve come to calling our Old Fashioneds the “2nd Best Old Fashioneds”.

So without further ado, we present to you, the Three 2nd Best Old Fashioned Recipes we’ve concocted over the years of making & savoring whiskey.

The Three 2nd Best Old Fashioned Recipes

The 2nd Best Old Fashioned Recipe No. 1

For this one, the splash of fresh orange juice is key, brightening up the cocktail for a perfect spring, summer, and (in the hot South) fall sipper. It pairs well with your lips, when you’re looking for something delicious.

- 2 oz Fiddler Unison Bourbon

- ⅓ oz Simple syrup

- 5 drops 1821 Prohibition Aromatic Bitters

- 5 drops 1821 Tart Cherry Saffron Bitters

- Splash Fresh orange juice

- Orange peel (for garnish)

Combine ingredients over ice, stir & strain into rocks/lowball glass over 2-3 ice cubes. Express* orange peel, rub around the rim, and drop into the glass.

*To “express” just means to squeeze it above the cocktail with the peel facing down, towards the cocktail.

The 2nd Best Old Fashioned Recipe No. 2

As pioneers in Southern pot-still spirits, this is the most traditional of the recipes we’ll put our stamp of approval on. It pairs well with cigars & fond memories of yesteryear.

- 2 oz Fiddler Unison Bourbon

- 2 tsp warm water

- 1 tsp raw sugar

- 3 dashes Angostura bitters

- Orange wedge (for garnish)

Stir sugar, bitters & water in a glass until the sugar is dissolved. Add 5-7 ice cubes and pour Fiddler over. Stir 20-30 seconds to chill cocktail & dilute whiskey, then strain into rocks/lowball glass. Garnish with orange wedge.

The 2nd Best Old Fashioned Recipe No. 3

This is the funkiest of the bunch, the proverbial wild child that pays homage to Georgia’s excellent, but often underappreciated, climate for some varieties of figs (specifically, “Brown Turkey” figs). It comes from our friends in Decatur, Georgia’s No. 246, just a hop, skip & a jump from our distillery.

- 2 oz Fiddler Unison Bourbon

- 2 tsp Fig cordial*

- 1 tsp Balsamic vinegar

- Regan’s Orange Bitters

- Lemon peel (for garnish)

So there you have it. Three variations of the 2nd Best Old Fashioned cocktail, as told by our distillery, which now just so happens to be a lively cocktail outpost as well. We hope you find these enjoyable, and likewise hope you'll join us for one at our tasting room some time in the not-too-distant future.

Cheers,

-Chad & The ASW team

Spirited Women Who’ve Run the World of Spirits

With International Women’s Day, we wanted to take a few moments to recognize some of the women who have helped shape the spirits landscape over the last century, ranging from Prohibition to modern-day.

Ninety-nine years ago, a bespectacled Ohio attorney who’d once been pitchforked by a drunk farmhand and a glacial Minnesotan with a mountain for a mustache guided the U.S. into one of its darkest ages. President Herbert Hoover called this era “a great social...experiment”. That was, of course, before the era abruptly ended thirteen years later. As you might have guessed, this Great Social Experiment was Prohibition. Or “Prohibition”, as anyone with a thirst for the bottle might have called it with a wink and a nod during the era. For speakeasies and locker clubs abounded in cities all across the country, catering to parched politicians and performance artists alike.

An International Women's Day Celebration

For International Women’s Day, we wanted to take a few moments to recognize some of the women who have helped shape the spirits landscape over the last century, ranging from Prohibition to modern-day.

Ninety-nine years ago, a bespectacled Ohio attorney who’d once been pitchforked by a drunk farmhand and a glacial Minnesotan with a mountain for a mustache guided the U.S. into one of its darkest ages. President Herbert Hoover called this era “a great social...experiment”. That was, of course, before the era abruptly ended thirteen years later. As you might have guessed, this Great Social Experiment was Prohibition. Or “Prohibition”, as anyone with a thirst for the bottle might have called it with a wink and a nod during the era. For speakeasies and locker clubs abounded in cities all across the country, catering to parched politicians and performance artists alike.

Meanwhile, “rum-running” entered the American lexicon as a euphemism for the tactics that spirited entrepreneurs used to evade authorities and get hooch into the hands of the people. Two of the most successful rum-runners during the era? A convoy-boat operator with the unassuming name of Marie Waite, and a pistol-wielding bosslady nicknamed “Cleo”, who hailed from the same state as the bespectacled attorney who ushered in the rum-running age: Ohio. Turns out, “women were far better bootleggers than men because many states had laws that made it illegal for male police officers to search women.” (Georgia Hopley, the first female Revenue agent, had this to say on the matter: “Their [women’s] detection and arrest is far more difficult than that of male lawbreakers.”)

The Bahama Queen of Whiskey

Gertrude Lythgoe was the tenth child of an English father and Scottish mother, a fitting lineage for a woman who would become one of the most successful Scotch whiskey runners during Prohibition. Spending some of her childhood as an orphan, she left her birth-state of Ohio, first for New York, then California, to work as a stenographer. Not long thereafter, she came within the orbit of a liquor exporter based in London.

After the passage of Prohibition in 1919, the exporter sent Lythgoe on special assignment to Nassau, Bahamas, to set up a wholesale liquor business. She wasted no time in opening their operations on Market Street. Sporting a pistol on her hip and poetry on her tongue, she earned the respect and admiration of her mostly male bootlegging peers, including the famed “Bill” McCoy. Earlier in life, her supposed similarity to Cleopatra earned her the nickname “Cleo”, and rum-running colleagues soon took the nickname to its logical conclusion by dubbing her “The Bahama Queen”.

Over the course of the next six years, she imported thousands of bottles of spirits into the United States. Though she was arrested on numerous occasions, the authorities could never get anything to stick, and she walked each time without ever receiving a conviction. Finally, in 1925, believing a “jinx” to be waiting in the wings for her, she retired from running whiskey across the Caribbean. “I just beat my jinx before it got me,” “Cleo” Lythgoe remarked the following year to the Milwaukee Journal. Taking an almost obituesque tone, the Journal wrote of her retirement:

A jinx has tracked her down, from her whisk(e)y throne in Nassau, through the most luxurious hotels of European capitals...to the loneliness of a New York hotel suite, where she came to hide from the world and recover her lost nerve and her health, attended only by her deaf mute sister.

Yet give up the ghost she had not, even if she’d given up the whiskey chase. She moved to Los Angeles and passed away in 1964 at the age of 86. Perhaps a multi-millionaire; or perhaps not. Nassau flags were raised to half-mast for days after her passing. It’s even rumored that “the British flag itself dipped in salute when, for the last time, she sailed from the Bahamas” during the height of Prohibition, to escape that jinx.

Whiskey in a Teacup, Rum in a Speedboat

Tom Waits may have considered his “Black Market Baby” to be whiskey in a teacup, but Marie Waite was anything but. Far from staying cool, she is rumored to have been both handy and unabashed in her use of firearms. After her husband Charles washed ashore near Miami in 1926, Marie assumed the mantle of leading the rum-running business he’d established, just months after Cleo Lythgoe had hung up her hooch boots. (Whether Charles died at the hands of a rum-running competitor, or in a shootout with the Coast Guard, is still a matter of debate.)

Based in Havana, “Spanish Marie” initially found success by transporting her cargo in a flotilla of four convoy boats -- three loaded with rum, one loaded with guns to fend off the Coast Guard. From these convoy boats, her employees offloaded the rum into 15 smaller contact boats, “the fastest in the business”, to run her rum anywhere from Palm Springs to Key West. At her peak, reports put her net worth at nearly $1 million. Her speed advantage, however, proved short-lived, as the Coast Guard upgraded their fleet and enabled them with radios.

But soon, Marie outfitted her boats with radios as well, and established an unlicensed radio-transmission station on Key West. Uttering seemingly random words in Spanish, her outfit evaded detection throughout the next hurricane season. Yet on March 12, 1928, authorities stumbled upon her and six accomplices in Coconut Grove, Florida, unloading whiskey, rum, champagne, and beer from her boat Kid Boots into a truck. They arrested her for the transportation of 5,526 bottles of alcohol. After posting a $500 bond, Marie skipped town. She was never heard from again.

The Women Making this Whole Thing Go

Back at the ranch (ASW) nearly a century later, we’ve been most fortunate to have two spirited women making this whole journey of ours go: Kelly Chasteen and Hallie Stieber. Both Georgia natives, their paths to whiskey were wide-ranging.

A Snellville native, Kelly -- whose teetotaler grandmother coincidentally shared the name Gertrude with the whiskey-running Bahama Queen mentioned earlier -- found a friend in Scotch-and-soda while at UGA and has been known to don a mean costume. If you’ve ever marveled at our tasting room’s design, reveled at a private event here, or traveled to ASW just for the fine assortment of locally crafted wares on our shelves, you can thank our Partner, Kelly Chasteen. Like a bootlegger of old, she has kept our whole enterprise going for months untold, sticking with it from the very beginning. Oh, and if you’re ever in a footrace with her, we highly recommend you stop immediately. She’s lightning quick and may or may not be regionally famous for outrunning the occasional gazelle.

A Marietta native, Hallie spent some of her childhood in that great bastion of cabbage patch-grown children, Cleveland, Georgia. Like Kelly, she stayed here in Georgia, the Empire State South, for her college days, before joining Empire State South in Midtown. Her palate led her to Kimball House, then on to Boccaluppo, where she managed the beverage program. Inspired by Negronis, Boulevardiers, and some of her other favorite classic cocktails, she crafts some mighty fine drinks and the events you get to enjoy them at.

Whiskey brings them together day in and day out. Not only because they work at a whiskey distillery. But also because they find it delicious -- Kelly predominantly bourbon, Hallie leaning more towards ryes and malts. We celebrate them (along with those spirited pioneers, Gertrude “The Bahama Queen” Lythgoe and “Spanish” Marie Waite) by raising a dram of whiskey. Thank y’all for all that you have done and continue to do.

Our 4 Year Journey to Duality Double Malt: The World's 1st Whiskey of Its Kind

Enter Duality, a testament to Justin’s 16 years of single-minded dedication to learning how to make some of the best craft booze in the world. Jim and Charlie met Justin over four years ago and immediately mapped out the idea for Resurgens. Hot on the heels of the idea for Resurgens, though, came Justin’s idea for a whiskey distilled from a mash of 50% malted barley and 50% malted rye. When he mentioned it to Jim one whiskey-sipping afternoon, Jim immediately coined the name “Duality”, a name that describes the dram better than any other could. Little did we know then that Duality is the first whiskey of its kind, anywhere in the world.

In following our progress through the years, you may have noticed a recurring theme: we rarely stick to a script, eschewing what’s conventional in favor of a trailblazing quest to remain true to our whiskey roots.

Our Start 7 Years Ago

When we prepared to first release American Spirit Whiskey seven years ago, we knew the uphill climb that awaited us with the little known category of spirit whiskey. But we liked the taste of the recipe we’d come up with, so instead of starting with vodka, we took a gamble with a clear whiskey. And though selling our clear whiskey for six years without a brown spirit as a portfolio mate could, with great accuracy, be described as “challenging”, or “tough sledding”, or “borderline madness”, we’re proud to look back and say that we remained true to our whiskey roots.

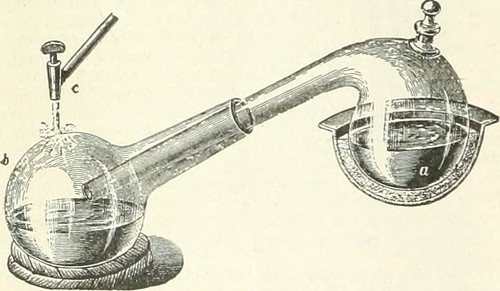

The Beginnings of Distillation at 199 Armour Drive

And when we began distilling on our ridiculously photogenic Scottish-style copper pot stills last year, we again parted with convention. The very first spirit we distilled was a whiskey of rye - but not cereal rye, which forms the basis of nearly all the ryes you find on the shelf today. Rather, malted rye, which uses the most pronounced form (malt) of the most flavorful grain (rye). As our fresh-distilled rye malt whiskey spent time in new oak barrels, it culminated in Resurgens, Atlanta’s first rye since Prohibition, and a unique one at that.

Photo credit: Chris Avedissian

Never ones to rest on our laurels, we next set out to create not just an Atlanta first like Resurgens, but a global first - one that we hope can help put Atlanta on the map internationally as a destination for world-class spirits.

The Blueprint for Duality

Enter Duality, a testament to Justin’s 16 years of single-minded dedication to learning how to make some of the best craft booze in the world. Jim and Charlie met Justin over four years ago and immediately mapped out the idea for Resurgens. Hot on the heels of the idea for Resurgens, though, came Justin’s idea for a whiskey distilled from a mash of 50% malted barley and 50% malted rye. When he mentioned it to Jim one whiskey-sipping afternoon, Jim immediately coined the name “Duality”, a name that describes the dram better than any other could. Little did we know then that Duality is the first whiskey of its kind, anywhere in the world.

An early prototype of the Duality type.

Hundreds of distilleries use 100% malted barley to create single malts the world over. Midleton in Ireland. Springbank in Scotland. Nikka in Japan. Us here in Georgia. And the list goes on.

Not to mention, a small but skilled handful of distilleries across the U.S. distill a mash of 100% malted rye to produce wonderfully unique whiskeys. In addition to us, San Francisco’s Anchor Distilling comes to mind.

But no distillery we've found has combined these two grains into a singularly flavorful whiskey distilled by pairing the traditional, Scottish-style double copper pot method with the Appalachian innovation of grain-in distillation. We’ve taken to calling Duality a “double malt”, in the most unique sense of the word(s).

We don't take the term “trailblazing” lightly. We wouldn't use it for what we're doing here if it weren't true. But, through all our years of challenging ourselves, pushing against our own personal limitations, we had - often unbeknownst to us - been setting the stage to push against the broader status quo’s limitations. In this case, the status quo of using malt only in the context of a conventional single malt crafted of malted barley.

A Defining Moment

Duality, then, represents for us a defining moment of sorts, arising from our team’s single-minded concentration on creating not only the best whiskey we can, but one that we hope serves as the touchstone whiskey for aspiring distillers in the years to come, much as Ireland’s Green Spot was for Justin nearly two decades ago.

Duality Double Malt, a whiskey that astounds writers and reviewers the world over with its flavor and finesse. A whiskey with a gorgeous label crafted with every bit of dual symbolism - including a quote from Shakespeare’s MacBeth - that we could pack into a single 5x4” piece of linen paper. And most importantly, a rich, complex whiskey with a dusting of smoke that helps you, our supporters, to forget - if even for just an hour - the trials and tribulations that life brings with it.

A fine label, indeed.

We would be honored for you to join us for this monumental release on Saturday, August 5, and share this finest of hours with us.

You may reserve your ticket to the release by following this link or clicking the button below.

Big News: We're Opening a 2nd Location

Seven years ago, we kicked our journey off in the humble confines of an Atlanta kitchen. We didn't know it then, but our first product, American Spirit Whiskey, was Atlanta's original Post-Prohibition whiskey brand and would soon gain a following around Atlanta as a perfect whiskey for those just getting into the category and others looking for an alternative to the common vodka. As the winds of change started to move Georgia's distillery laws in a favorable direction, we decided to start looking for a place to call our own - a place to locate our own distillery in the heart of our hometown making the spirit we'd loved since our days at the University of Georgia.

The Way Back

Seven years ago, we kicked our journey off in the humble confines of an Atlanta kitchen. We didn't know it then, but our first product, American Spirit Whiskey, was Atlanta's original Post-Prohibition whiskey brand and would soon gain a following around Atlanta as a perfect whiskey for those just getting into the category and others looking for an alternative to the common vodka. As the winds of change started to move Georgia's distillery laws in a favorable direction, we decided to start looking for a place to call our own - a place to locate our own distillery in the heart of our hometown making the spirit we'd loved since our days at the University of Georgia.

The Search

Our search took us all over the city: from West Midtown to Buckhead to, eventually, Third & Urban's Armour Yards, where we settled on a space in the same neighborhood that had originally attracted SweetWater Brewery, the Atlanta Track Club, and Fox Bros. BBQ. For the last year and with Athens, Georgia's craft booze legend Justin Manglitz at the helm, we've been distilling at our 199 Armour Drive distillery, combining traditional, Scottish-style copper pot stills with the Appalachian innovation of grain-in distillation - one of the few distilleries in the country taking such an approach.

The Westward Expansion

The last seven years since those humble days in an Atlanta kitchen, and the last year in our Armour Yards digs have brought with them untold sweat, stress, and the sacrifice known as sipping whiskey. Now, with our distilling maestro Justin Manglitz at the helm and the incredible support you've provided us since our Grand Opening last year, we've decided to set off headlong into the next leg of our whiskey expedition: a westward expansion.

As of this week, we have come to terms with Stream Realty to open our 2nd Atlanta location, The ASW Rickhouse, joining our craft brewing friends Monday Night Brewing and Wild Heaven in Atlanta's vibrant West End neighborhood. Not to mention, we'll also be able to stave off the type of hunger known to occasionally accompany whiskey consumption with Atlanta icons Honeysuckle Gelato and Doux South Pickles as neighbors.

Wes Jones, Honeysuckle Gelato's co-founder, had this to say about us joining the fun:

I’m thrilled that ASW Distillery will join the fun at Lee + White. Jim and Charlie have put together an incredible team, a group that will enhance the collaborative environment being created at Lee + White. We at Honeysuckle Gelato are looking forward to welcoming ASW to the West End's burgeoning food family.

When our current barrel house gradually then suddenly became saturated with barrels of delicious whiskey, we sought a space that would allow us to continue to play a role in Atlanta's spectacular resurgence, while expanding our storage capacity to help us in our endeavor to put Atlanta on the map for craft distilling. With Monday Night Brewing and Wild Heaven - the founders of whom we've been friends with for over a decade - joining the Lee+White development, the choice was easy, and obvious. Like deciding between whiskey and V8.

Monday Night’s Jonathan Baker expressed enthusiasm for ASW Distillery’s decision:

We’re excited to continue our friendship with ASW, in no small part because we’ll have a perfect spot to walk to after work for a whiskey or three. We started out as neighbors, living next door to each other and brewing in the garage, and now we get to be literal neighbors again.

Meanwhile, ASW Distillery’s Head Distiller, Justin Manglitz, has known Wild Heaven’s Brewmaster Eric Johnson for years, since Manglitz’s days owning downtown Athens, Georgia’s home brew supply store, where Eric was one of his biggest customers. Of ASW Distillery’s westward expansion, Wild Heaven’s Johnson noted:

We are thrilled that ASW has decided to officially become our neighbor in the exciting Lee+White development on the new West End Beltline. They are a perfect fit with the growing community of creatives who have decided to make L+W their home. They are long-time friends who make amazing spirits and we look forward to continuing our many collaborations with them in the years to come.

As such, The ASW Rickhouse will increase our total barrel storage capacity to nearly 1,500 barrels and will provide a convenient spot for our CEO Jim to take a nap, away from the watchful eyes of Justin.

The Other Great News

The timing could not be more right, either. Earlier this week, Governor Nathan Deal signed SB 85 into law that, among other things, allows distillery guests starting this September to sample any of our whiskies in either flight or cocktail form. So no more difficult choices as you peruse our six (and growing) spirits offerings.

The law represents a true game-changer for us and our craft brewery cousins, allowing us to thrive and continue to provide Georgians with a plethora of local craft options.

With all of these incredible encouraging developments fueling us forward, we could not be more excited to share this next, pioneering chapter in our history with you.

To that end, we would be most honored if you would kindly share this exciting news with your friends, on any of the below mediums:

Thank you so much for your ongoing support. We absolutely cannot do it without you and hope to continue to be able to share our journey with you over the weeks, months, and years to come.

The first of many great whiskies to come

Do y’all remember Atlanta’s original craft breweries? We’re talking Marthasville, formed in 1994; Atlanta Brewing Co., formed in 1994 and later renamed Red Brick Brewing Co.; Dogwood, formed in 1996; and of course, Atlanta’s biggest craft brewery to date, SweetWater, formed in 1997.

These were Atlanta’s craft beverage pioneers, paving the way for the incredibly rich and diverse craft beer scene we enjoy in Georgia today. Without their hard work and determination, Georgia’s libations landscape would be significantly less interesting. And we here at ASW Distillery would likely not have had a remote chance of trying to help put Atlanta on the map for craft whiskey.

Do y’all remember Atlanta’s original craft breweries? We’re talking Marthasville, formed in 1994; Atlanta Brewing Co., formed in 1994 and later renamed Red Brick Brewing Co.; Dogwood, formed in 1996; and of course, Atlanta’s biggest craft brewery to date, SweetWater, formed in 1997.

These were Atlanta’s craft beverage pioneers, paving the way for the incredibly rich and diverse craft beer scene we enjoy in Georgia today. Without their hard work and determination, Georgia’s libations landscape would be significantly less interesting. And we here at ASW Distillery would likely not have had a remote chance of trying to help put Atlanta on the map for craft whiskey.

We’ve joined just three other Atlanta-area craft distilleries in trying to provide you with spirits that you can call your own hometown spirits: from Lazy Guy’s bourbon & rye, to Old Fourth’s vodka & gin, to Independent’s rum & bourbon. Our own contribution ranges from two forthcoming bourbons, to brandies if fruit prices ever go back down, to single malts to write home about, made from 100% malted barley and 100% malted rye.

This last spirit, our single malt made from 100% malted rye, is one of just a handful in the country. But we didn’t make it just to be different. (Although we do like to blaze some trails and push some envelopes when we can - it's far better than pushing paper, which 2 of the team members did for many years.) We made it in homage to the single malts we’ve loved for years, fashioned on the same Scottish-style double copper pot stills that some of our favorite Scotch and Irish Whisk(e)y distillers have used for centuries. (Macallan, anyone?) We made it as a testament to one of Georgia’s native grains, rye, which has grown here for centuries. Far better than the European import known as barley.

Yet we also made our Single Malt Rye as a way to show the innovative flavor profiles you can achieve by experimenting with grains. Just like the craft beer pioneers before us — who showed how delicious heavily hopped beer can taste, and how damn good a sour ale brewed using wild, unpredictable yeast can be — we wanted to give Atlanta something unique to call its own, a style of delicious whiskey you find almost nowhere else in the U.S., let alone Georgia.

We’ve put most of it in new, American oak casks to mature for a later date. Not to mention, we enlisted the talents of one of Georgia’s best artists to design the label. More on that to come.

But in the meantime, we’ve bottled some of this groundbreaking Single Malt Rye before it spends time in oak. You’ll notice it’s incredibly smooth for the 93 proof we bottled it at, and has interesting notes of chocolate, hazelnut, and pepper. As it spends time in a barrel, it will take on some of the toffee, caramel, and vanilla notes you expect of a Highlands single malt, and may even present hints of Georgia’s terroir in its tasting notes, like cooked peaches and dried figs.

We look forward to sharing our spirits with you, helping put Atlanta on the map when it comes to craft distilling, and providing you with your very own hometown whiskey for years to come. Thank y’all for sharing in our journey.

Foiled sieges and fake cats: the history of the modern bar

In 1920, a young Atlanta alderman by the name of William Hartsfield began reading speculative literature on the future of what many believed would become a way to transport mail faster. A few visionaries spotted the much more wide-reaching implications of this newfangled technology, the airplane. Hartsfield was one of them, and soon learned of the United States Postal Service’s plan to locate a refueling hub between its New York City and Miami airports for mail planes.

In 1920, a young Atlanta alderman by the name of William Hartsfield began reading speculative literature on the future of what many believed would become a way to transport mail faster. A few visionaries spotted the much more wide-reaching implications of this newfangled technology, the airplane. Hartsfield was one of them, and soon learned of the United States Postal Service’s plan to locate a refueling hub between its New York City and Miami airports for mail planes.

Hartsfield jumped at the opportunity, working together with then-Mayor Walter Sims to secure a five-year, rent-free lease on an abandoned racetrack known as the Atlanta Speedway. Hartsfield partnered with Atlanta’s chief of construction, W. A. Hansell, to transform the speedway into a proper airfield, sodding the field with truckloads of manure that caused an outcry from residents of the downfield town of Hapeville.

As the date the federal government planned to open bidding approached, Hartsfield turned his attention to gaining longer-term access to the land by naming the airstrip Candler Field, a sycophantic ploy to win the loyalty of Asa Candler Jr., who held title to the land. Unswayed by flattery, the eccentric Candler — of Coca-Cola lineage who kept a menagerie of wild animals at his mansion — ensured Hartsfield he would demand payment in full for the property when the five-year lease ended.

When bidding for the postal service refueling station finally opened in 1926, Atlanta submitted its bid with bated breath. To Hartsfield’s chagrin, Atlanta’s westerly neighbor Birmingham submitted a bid for the refueling hub as well. At the time, the cities were nearly identical in regional influence and size, at around 200,000 residents apiece. And Birmingham was perhaps even more strategically located when one examined a map.

Hartsfield went to work, organizing a trip for an assistant postmaster general to visit Atlanta and inspect Candler Field. When the assistant arrived, Hartsfield ferried him across the city with a motorcade flanked by an eight-motorcycle escort. That evening, the scion of Atlanta’s banking community, John K. Ottley(1), Mayor Sims, Georgia Governor Clifford Walker, and Hartsfield, among many others, wined and dined the official before sending him off to a luxury hotel suite for the evening. As Hartsfield later gloated, “No east Indian potentate ever got the attention he did.”

A week later, the Commerce Department designated Atlanta as a stop on the federal airmail route. Hartsfield had, almost singlehandedly, paved the way for Atlanta to become the South’s — and, later, the nation’s — busiest flight hub, connecting millions of national and international visitors every year.(2)

Three centuries before airports became symbols of a city’s connectedness and Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport put Atlanta on the map internationally, Vienna and London were in the midst of their own connectivity renaissances. Unlike the twentieth century’s hubs, in which visitors speaking languages of all stripes sipped lattes and lagers while reading the New York Times between flights, Vienna’s cafes and London’s gin joints were far more provincial in nature. Yet they, like the airport, brought far-flung citizens together like never before.

A siege before the caffeine surge

The Ottoman Empire once stretched from the Persian Gulf in the east to the piedmont just west of Venice’s canals, a distance the equivalent of Atlanta to San Francisco. At the height of its imperial efforts, the Ottoman Empire made multiple attempts to sack the Habsburg Dynasty’s cultural hub of Vienna — first in 1529, another in 1683. Each time, the Viennese rebuffed the onslaught by the Ottoman troops. The story goes that in the aftermath of the Second Siege of Vienna, the Viennese found sacks of strange beans they originally believed to be camel feed. Rather than disposing of the beans, Polish king Jan III Sobieski, who had helped defend Vienna, gave them to one of his officers, Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki — the uncanny resemblance to the story of Jack and the Beanstalk, be damned.

It was the first time on record coffee had made its way to Europe — it was welcomed with as much aplomb as tobacco had been received on Columbus’ return from the “West Indies” 200 years prior. Kulczycki soon opened Vienna’s first coffeehouse.

Cafe Griensteidl: the First Starbucks?

The next 200 years saw Vienna’s coffeehouse culture grow and thrive. So much so that “by 1900 they had evolved into informal clubs, well furnished and spacious, where the purchase of a small cup of coffee carried with it the right to remain there for the rest of the day…Newspapers, magazines, billiard tables, and chess sets were provided free of charge, as were pen, ink, and (headed) writing paper.”(3)

These caffeinated social clubs helped distinguish Vienna from other cultural centers like Berlin, Paris, and London — the last of which was, concurrent to the Viennese cafes, pronouncedly more besotted, as we’ll explore below.

The most famous of Vienna’s coffeehouses, Cafe Griensteidl, saw many influential authors and philosophers of the early 1900s enjoy a cuppa, including, Hugo von Hoffmansthal, Theodor Herzl, and likely Sigmund Freud himself, although he found Vienna provincial and preferred Swiss cities.

Today, we still enjoy the legacy of these Viennese coffeehouses when we order a latte at a Starbucks coffee bar, pour half the contents out, and fill the space with whiskey from a hip flash that we carry around in our left boot. Our cafes today carry a mantle borne down through the ages by West Coast entrepreneurs, who perfected the Viennese model by adding a dash of indie music and bespoke-seeming branding before scaling the concept to the rest of the world.

The rise of the London dram shop

Five years after Kulcynski opened Vienna’s first coffeehouse, achipelagic Europeans — Londoners, more specifically — got their first taste of gin when William of Orange acceded to the throne. For years, French brandy had been the British spirit of choice, but political and religious conflict between the cross-Channel neighbors led the British Government to pass various acts restricting brandy imports. In 1690, the Government ended the monopoly held for years by the London Guild of Distillers. A range of distillers dove headfirst into the deep ends of the gin pool, encouraged by various politicians, including Queen Anne herself.

As more efficient industrial agriculture practices drove food prices down, Brits — especially cosmopolitan Londoners — had more disposable income. Lacking bowling alleys and Bieber concerts, Londoners took to drink as a form of communal gathering. Centuries prior, visionary entrepreneurs had foreseen that many Brits preferred to down their drinks away from the confines of their homes and had thus introduced thousands of taverns, inns, and alehouses across the country. There, patrons would gather around rough-hewn tables to drink tankards of ale and presumably plot coups that never made it past midnight.

Gin joints & miserable livers

Gin revolutionized these parochial gathering places. Instead of serving patrons at picnic tables, the proprietors of “dram shops”, as they came to be called, centralized distribution of beverages at a main bar. These “gin joints” blossomed throughout the early 1700s, and Brits’ spirits consumption tripled. As early as 1721, Middlesex magistrates decried the pervasive drunkenness they witnessed in the streets. Moving swiftly, they helped pass the Gin Act of 1736, which taxed retail sales of gin at 20 shillings a gallon and required gin joint proprietors to pay a £50 annual license — roughly £7,000 at today’s rates — all but pricing out everyone in the market.

Wily barkeeps introduced an ingenious mechanism to circumvent the de facto prohibition imposed by the 1736 Gin Act. Thirsty Londoners would deposit a shilling in a cat’s paw outside of an unassuming residence. The shilling traveled down a tube, and when the barkeep inside received the money, the barkeep would pour a shot’s worth of gin down the tube to the patron’s mouth. Thus was born the precursor to two 20th century innovations: the Prohibition-style speakeasy, and the modern-day ice luge.

Old Tom Gin & Prohibition-era preferences

The gin-paw invention was known as “Old Tom” — an homage to the tom cat that served as gin courier. In time, gin earned the nickname “Old Tom” as well, specifically a type of sweeter gin. The name still stands today with brands like Ransom Old Tom Gin and Anchor Old Tom Gin leading the craft spirits category.

A century after the first gin joints opened, they resurfaced serving not just gin, but wine and beer as well. They were the precursor to the modern bar as we know it.

Of course, the party didn’t truly start until proprietors added whiskey to the fray. By the time the U.S. enacted that Great Failed Experiment, Prohibition, in 1920, rye whiskey had replaced cognac as the spirit of choice, planting itself firmly in the minds of thirsty bar-goers. Prohibition was to the whiskey industry nothing short of an earthquake — a rifting of plates, a shifting of palates.

Post-Prohibition plate tectonics

In the winner’s circle: Blended Canadian whiskey, with its mild manners and smooth finish, vaulted like an Olympic gymnast into the minds of consumers. Not to mention:

In the post-Prohibition era, bourbon proved as resilient as the corn it derived from.

Not making the podium: Rye whiskey fell off the bar stool, and nearly off the map. Irish whiskey, in the wake of Prohibition and the 1919 closure of British markets, almost went extinct entirely.

A modern-day renaissance

But today, we’re seeing many delicious pre-Prohibition styles of spirit make a comeback. Old Tom Gin and its more mature cousin, barrel-aged gin, are seeing glimmers of shelf space. Irish whiskey is in the throes of a real heater. And perhaps most warming to us: rye whiskey is in the midst of a renaissance.

Why so warming to us? Because the first spirit off our Scottish-style twin copper pot stills is no less than a whiskey made from 100% malted rye, one of America’s native grains.

While we’ve barreled 95% of this American Single Malt Rye, we’ve chosen a select number of bottles to release to you, our early supporters. This one-time-only release offers a taste of delicious chocolate, hazelnut & pepper notes before the single malt spends time maturing in new American oak casks to become what may very well be the quintessential Southern single malt whiskey.

Join us for BBQ, Bluegrass, and Our First Bottle Release on Saturday, September 10 to help us celebrate this milestone for what we hope may very well become the quintessential Southern single malt whiskey and help put Atlanta on the map when it comes to craft whiskey.

Not to mention, each pass comes with a tour of the production area, including our gorgeous, hand-hammered copper pot stills and our rickhouse full of new American oak barrels.

We hope you’re as excited about this monumental event as we are.

— — — — —

(1) Our neighbor street in Armour Yards is Ottley Drive.

(2) Allen, Frederick, Atlanta Rising, Taylor Trade Publishing (1996)

(3)Watson, Peter, The Modern Mind: An Intellectual History of the 20th Century, Harper Collins (2011).

Bourbon vs. Whiskey: What's the difference?

When you were in kindergarten, you likely weren’t a regular bourbon drinker. In fact, you probably didn’t yet know much about bourbon. This makes sense, as teachers are busy teaching you the basics of counting and cooperation, leaving little time to instruct you in the finer spirits of life. As you matured through the years like a fine bourbon in new charred American oak barrels, you likely developed a taste for Scotch, or bourbon, or rye whiskey. (We base this assumption on the fact that you’re here, and all we write about is whiskey.)

When you were in kindergarten, you likely weren’t a regular bourbon drinker. In fact, you probably didn’t yet know much about bourbon. This makes sense, as teachers are busy teaching you the basics of counting and cooperation, leaving little time to instruct you in the finer spirits of life. As you matured through the years like a fine bourbon in new charred American oak barrels, you likely developed a taste for Scotch, or bourbon, or rye whiskey. (We base this assumption on the fact that you’re here, and all we write about is whiskey.)

Yet sometimes our palates precede our knowledge. Many folks who’ve joined us for tours since we opened have oft-repeated the question: “So what’s the difference between bourbon and whiskey?”