CRAFTED WITH CHARACTERS

A collection of our thoughts on whiskey, spirits

&

the world

Weekend Roundup: July 15

--A jaunt through Islay & the history of its formation & whisky distilleries by The Guardian: http://buff.ly/29XoR21

--An interesting new rice whiskey by the name of Kikori. The NY Times says it has hints of ginger: http://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/06/dining/kikori-whiskey.html?_r=0

--What does a red-oak-smoked corn malt whiskey taste like? Apparently, somewhat like BBQ, or the perfect aperitif to it. http://thewhiskeywash.com/american-whiskey/whiskey-review-revelations/

--Americans are becoming more experimental in their Scotch selections - a good sign for American single malts, from Fortune Magazine http://buff.ly/29FqXYU

--From Popular Science: What Does The Deadly Oak Epidemic Mean For Whiskey? There's a deadly disease affecting oaks of California and the Pacific Northwest. As a distant cousin of the disease that cause the Irish Potato Famine, it's not new, but it's spreading and means business. http://buff.ly/29SoSbz

--On American single malt whiskey, including the superb Old Potrero rye malt by Anchor Spirits. Which reminds us, we've got a rye malt on the way, due out next year. http://buff.ly/29S9edC

Weekend Roundup: July 8

Hope everyone had a great 4th! Now that we're back, let's get this whiskey knowledge train back on the tracks.

--The Daily Beast, on the main source of many craft rye whiskies you'll find state-side: Canada. Specifically, Alberta, where they've been making great rye for years. http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2016/06/28/your-local-craft-whiskey-may-really-be-from-canada.html

--On the Pattison Crash the decade after the 1896 bankruptcy of Scotch whisky speculator Pattison, Elder, by the Whiskey Wash http://buff.ly/2944eS4

--On proofing down whiskey (adding water to it) to achieve consistent flavor profiles and avoid saponification (water bringing out fats from suspension and creating a soapy taste), by the Whiskey Wash

--And in case you missed it on Crafted with Characters, we cover a similar topic in: Whisk(e)y: Neat, with water, or on the rocks? http://bit.ly/neat-or-water

--We also discuss the history behind the whiskey (with an "e") vs. whisky (with the "e") debate here: http://bit.ly/e-or-no-e

--On the re-emergence of artfully blended whiskey, including craft pioneer High West's Bourye, from Bloomberg http://buff.ly/29dyD1y

--Tastebuds & whiskey, WFPL on the differences in the way that women and men taste whiskey: “Pikesville Rye...topped the women’s chart...Elijah Craig...was the men's pick” http://buff.ly/29gYbIZ

"It's not spelled with an e." A brief history of the whisky vs. whiskey debate

One rather balmy December day nearly eight years ago, celebrated New York Times author Eric Asimov published an in-depth piece comparing a number of 12 year old Speyside Scotches. Within hours, single malt enthusiasts the world over had left him angry messages.

Was it because he’d rated The Glenlivet above Macallan? Or had he perhaps done the unthinkable and added ice to the tasting?

Neither, it turns out.

One rather balmy December day nearly eight years ago, celebrated New York Times author Eric Asimov published an in-depth piece comparing a number of 12 year old Speyside Scotches. Within hours, single malt enthusiasts the world over had left him angry messages.

Was it because he’d rated The Glenlivet above Macallan? Or had he perhaps done the unthinkable and added ice to the tasting?

Neither, it turns out.

Rather, he’d scattered the offensive letter “e” all about his article in the worst of places — between the “k” and the “y” in the word whisky. One commentator even found Asimov’s use of “whiskey” to make the “article quite unreadable,” a faux pas that “a reputable writer should not make.”

The source of the outcry is not simply a case of lexical whimsy. The genesis of these Scotch enthusiasts’ anger dates back centuries, highlighting rivalries between the British Isles second and third most populous countries.

Some claim that the linguistic rift began when frugal Scottish printers found they could save money by shedding vowels from words like a sinking boat jettisoning anvils.(1)

Others claim that the spelling divergence arose in the 1870s, when Irish distillers sought to distinguish their spirit from the Scottish swill that had flooded the market after the advent of the Coffey still.

The type of still that once ruled Scotch.

Regardless of the source of the rift, the difference in spelling is not merely an exercise in academic nerdery. Both the Scottish and the Irish seem to find — bound up within the spelling — a symbol of their culture; as one critic of Mr. Asimov summed up in asserting the use of “whiskey” in reference to Scotch: it’s “an embarrassing solecism unworthy of the New York Times.”

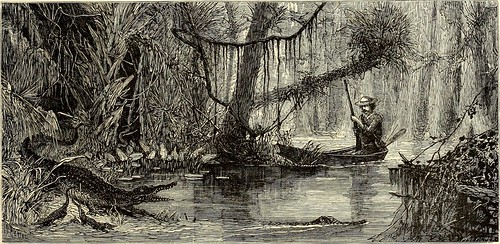

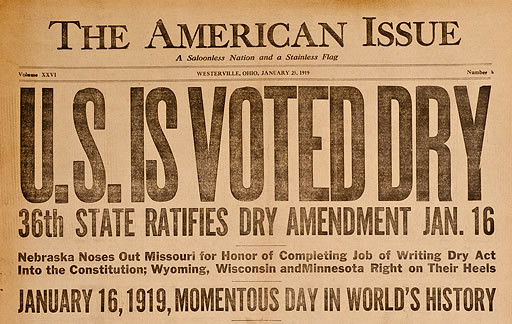

This makes sense. The Scottish and Irish have a centuries-old, somewhat friendly rivalry (2)— the type of rivalry that claims sports and spirits as its main sticking points. Adding fuel to this rivalry, Scotland likely pilfered the concept of whisk(e)y — or uisge baugh, as the Irish called it — then proceeded to become the dominant exporter of the spirit worldwide, while Ireland’s whiskey industry struggled through multiple internecine and international wars, along with U.S. Prohibition.

If the difference in usage stopped with just Ireland and Scotland, there wouldn’t be much to worry about. Just like the “i before e, but not after c” rule, we’d memorize it and be done.

But bright line rules are for managers and mathematicians, not whiskey-makers. A world without complexity wouldn’t need whiskey in the first place. So to complicate matters, since the original linguistic split between Ireland and Scotland centuries ago, the U.S. has for the most part adopted the Irish spelling, while Canada and Japan have opted for the Scottish spelling.(3)

A world without complexity wouldn’t need whiskey in the first place.

Newer distilleries opening as far afield as India and Australia often choose the Scottish spelling as well, likely due to the reputation for quality that Scottish distillers have given to the term “Scotch whisky” in the past few decades. Even a few distilleries in the U.S. elect to use the Scottish spelling — Maker’s Mark chief among them — which likely stem from the companies’ Scottish heritage.

But not all newcomer distilleries prefer the Scottish spelling. Take for example, Mexico’s Dorwart Whiskey, which prints “Whiskey” prominently on the front of each bottle.

Dorwart’s market entry confounds the catchy rule that many whisk(e)y writers had developed through the years to remember which spelling goes with which country. The rule went something like this: if the country has an “e” — namely, Ireland and the United States — its spelling of whiskey does, too; if the country lacks an “e” — namely, Scotland, Canada, and Japan — its spelling of whisky does, too.

Nowadays, perhaps the easiest rule to remember, if you’re into accuracy, is that the place that made whiskey first (Ireland), the place that made whiskey most recently (Mexico), and the place that makes whiskey the best (United States) all use the “e”.(4) Everyone else sheds the "e".

When referring to the spirit generally, you can refer to it as whiskey with the "e", as is the custom here in the US. But if you come within ten characters of the word Scotch, you'd be well-advised to drop the "e" like the Dodgers dropped Brooklyn almost a half-century ago. Even the New York Times Monsieur Asimov might agree.

— — — — —

(1) To which the Scottish retort: “It only takes us two distillations to get it right” — a direct jab at the traditional Irish method of triple distillation.

(2) Some Irish don’t necessarily view it as quite so friendly.

(3) Japan’s use of “whisky” makes sense, as the godfather of Japanese whisky, Masataka Taketsuru, trained at the now-defunct Hazelburn Distillery on Scotland’s Kintyre Peninsula. Canada’s adoption of “whisky” may reflect its historic ties with the Crown.

(4) We jest. In addition to distilleries in the US, distilleries in Japan, Scotland, and Taiwan all bottle some of our favorite drams of all time.

Whisk(e)y: Neat, with water, or on the rocks?

Imagine yourself cooking chili. You add meat and onions, then tomato. As a self-proclaimed Master Chili Chef, you naturally add salt to taste as the chili cooks. You sprinkle some salt into the pot, ladle some from the pot to taste, and decide it needs more salt. So you go to add a dash more salt and…the shaker’s top falls into the pot.

Imagine yourself cooking chili. You add meat and onions, then tomato. As a self-proclaimed Master Chili Chef, you naturally add salt to taste as the chili cooks. You sprinkle some salt into the pot, ladle a spoonful of the stew to taste, and decide it needs more salt. So you go to add a dash more salt and…the shaker’s top falls into the pot.

Salt cascades into the chili. Finally, you regain your wits and twist the salt shaker upright. But now, aside from this unfortunate scenario belying your claim to kitchen mastery, you’re faced with a conundrum: what to do with your overly salted chili?

This is too much salt for chili.

You consider throwing it out. But that would mean admitting to your spouse that you don’t actually know what you’re doing in the kitchen. So you decide to salvage it doing the only thing you know how: adding more ingredients.

To many starting their whisk(e)y journey, cask-strength expressions of 50%+ alcohol can trouble the palate like heavily-salted soup. (Of course, our Resident Salt Junkies, who will remain unnamed, might make the claim that soup can never be too salty.) One hundred twenty proof alcohol is just plain hot, the type of hot you find in south Georgia just shy of September.

Distillers know this, so absent the rare occasion of a cask strength release, they “proof down” or “cut” a spirit after pulling it out of casks (or barrels, depending on the size) to a less palate-eviscerating 80, 86, or 90 proof. This is the strength of the whisk(e)y when it joins fellow bottles in your home bar. [Note: we'll just use the term "whiskey" from here on out, as is the common usage in our jurisdiction.]

But now, just like with your chili, you must decide whether to add something to the whiskey to achieve tippling harmony - in this case, water.

As with many things in the lives of barristers, businessmen, and bourbon-makers, the answer is: It Depends. In this case, it depends on what your goal is.

With water

Adding a few drops of water to your whiskey breaks the surface tension that binds the whiskey molecules. The ensuing chemical reactions generate heat, which unlocks more aromas lying dormant in the whiskey. Spirits judges the world over proof down whiskies for this very reason — to fully evaluate a spirit’s varied aromas.

Some folks claim that you should proof down whiskey only with water from the distillery's own water source. However, this is not only impractical, but also a step that many world-renowned Scotch distilleries focused on achieving economies of scale(1) forgo in favor of diluting to bottle strength with water not from their distillery's local water source, but from Edinburgh or Glasgow.

So if you do decide to add water to experience the full gamut of sensory aspects a whiskey can provide, ignore this notion that only the distillery's water will do. and feel free add a few drops from any bottled or well-filtered water, preferably after tasting it neat.

Neat

Many whiskey enthusiasts, including at least one amongst our ranks, view the addition of water as roughly equivalent to rubbing Behr paint on a Rembrandt. The thinking here is that, without water, “you are tasting it in the natural form with all of the original distillery characteristics and flavors.” Source.

Behr paint would not augment this Rembrandt in acceptable fashion.

This first point is fair. But some take the argument a step further and claim that whatever proof a distillery bottles a spirit at is the proof it has determined as the strength at which you’ll best enjoy the spirit. While there may be some validity to this claim, in practice, a distillery may find that 48.4% is the ideal proof at which to enjoy a particular whiskey, but will instead bottle at a round number to simplify bottling.

So if you want to enjoy the whiskey in its original state, feel free to do so by drinking it neat; just avoid the claim that whatever proof the distillery bottles the spirit at is the singly perfect proof for the spirit.

On the rocks

Some whiskey enthusiasts — especially ones who live in regions that some might describe as “subtropical” and others might describe as “swamp-like” — find their shirts coagulating with moisture during the summer months. In these tepid times, we’ll occasionally turn to the wonders of the nineteenth-century innovation known as “ice”, first harvested in 1806 by the enterprising New Englander, Frederic Tutor.

South Georgia today not so very different than this woodcut.

Although ice actually suppresses the aromas (or nose) of whiskey, when your A/C unit goes out during a heatwave and you find yourself laboring away over a pot of soup, there’s little more you can do.

So when you do find yourself looking to place ice in your whiskey to cool down during a heatwave, do so with large cubes like these that melt slower while still chilling your tipple.

Our approaches

All in all, we typically find that well-made spirits do reveal a different complexion once we add a few drops of water. So, when we’re really trying to evaluate spirits, we first inhale the whiskey aromas at bottle proof in a few, quick sniffs, let the spirit rest, then take deeper breaths. Once we’ve done this, we often add a drop or two of water to let the spirit open up and repeat the process. If the whiskey is still quite hot, we might undergo this process once or twice again.

But we always do so gradually. Because —similar to the case of chili, which requires proportionally more ingredients once you’ve skillfully over-salted it—if you add too much water to whiskey from the outset, you’re left with the very real dilemma of adding more whiskey to regain the dram’s harmony. Of course, this is only a problem when we’re evaluating spirits for consistency. When we’re evaluating spirits for clarity on the great mysteries of life, adding more whiskey to a glass is generally a solution.

— — — — —

(1) As the Birthplace of Economics, it makes sense that Scotland has given birth to distilleries that favor one of the linchpins of modern economics: economies of scale.

Weekend roundup: June 24

--The Whiskey Wash on a vital part of the distilling process: yeast. "“Today, most Scottish distilleries use one of a handful of similar yeasts from the 'M' strain.” More here: http://buff.ly/1OuvM4N

--Irish whiskey & Scotch continue to surge: up 159% & 85%, respectively, since 2010. More on the industry by Forbes at: http://buff.ly/23gimfm

--Great Crave piece on Islay: The Island Built on Scotch and Sheep - http://buff.ly/1Udu5pw

--And in case you missed it, here's our take on that same island of Scotch, sheep, and drams: http://bit.ly/notes-on-islay

--In less rosy news, speculation on what Britain's recent exit from the EU means for Scotland's most famous export. In a nutshell: tariffs on Scotch may go up, reducing demand on the European mainland. http://finance.yahoo.com/news/brexit-whiskey-whisky-scotch-bourbon-shortage-alcohol-spirits-175839745.html

--Speaking of islands that produce Scotch, here's a nice primer on The "other" Islands of Scotch (Jura, Orkney, and the like), with mentions including Highland Park and Scapa Distillery http://buff.ly/28JpvS1

--An interesting post from one of the bourbon industries scions about the falsity of Jack Daniel's 150 Year Anniversary claim this year: http://chuckcowdery.blogspot.com/2016/06/today-jack-daniels-celebrates-its-fake.html

--Whisky from Down Under! Limeburners is superb - from both our experience with our Master of Malt advent calendar this year & Whiskey Wash's recent review: http://buff.ly/28WFAWM. Curious about whisky from other strange global locales? Look no further than Crafted with Character: http://aswdistillery.com/crafted-with-characters/7-countries-youd-never-guess-make-great-whiskey

--With women leading the resurgence of bourbon, it's great to see women forging new paths with distilleries as well, like Republic Restorative in DC in this exploratory post: http://buff.ly/28S1tkj

--On the role copper plays in distillation, from the great folks over at Whiskey Wash: http://buff.ly/295xzeb

All barrels are casks but not all casks are barrels

Casks are like the middle children of the aged spirits world. They don’t have the upscale industrial aura of the shining beacons of the spirits world — the stills that produce the spirits. Nor have they the multi-sensory appeal of the finished whiskey.

But casks play a huge role in helping shape the final flavor profile of not only spirits aged in them, but wine and beer, too. They can impart flavors as wide-ranging as vanilla, coconut, and oak, and — when charred on the inside — help charcoal filter the spirits into smooth-sipping glory.

Casks are like the middle children of the aged spirits world. They don’t have the upscale industrial aura of the shining beacons of the spirits world — the stills that produce the spirits. Nor have they the multi-sensory appeal of the finished whiskey.

But casks play a huge role in helping shape the final flavor profile of not only spirits aged in them, but wine and beer, too. They can impart flavors as wide-ranging as vanilla, coconut, and oak, and — when charred on the inside — help charcoal filter the spirits into smooth-sipping glory.

The first thing to know about “barrels” for spirits is that this term is not technically a catch-all for any vessel used to age spirits. Rather, a “barrel” is a specific term of art in the beverage industry referring to a 50–53 gallon (180–200 liter) cask, often made of white oak.

For the all-encompassing term for the vessel that you age spirits in, “cask” is the preferred nomenclature.

Kind of like how we learned in kindergarten that all squares are rectangles, but not all rectangles are squares, the same holds true here: all barrels are casks, but not all casks are barrels.

A definitive list of all different types of casks is available here, but the main types to know for the purposes of American whiskey are:

- Gorda — 185 gallons. Made from American oak. Their large size makes aging a long and arduous journey through the decades (less oak surface area coming into contact with the liquid), so these casks are perhaps best used to marry different whiskeys.

- Port Pipe — 172 gallons. With European oak as their base, these cylindrical (dare we say “pipe-like”?) casks first age port and often reinvent themselves as second use barrels in Scotch distilleries. More recently, American craft distillers have taken a liking to them in helping expand American whiskey’s flavor horizons.

- Sherry Butt — 126–132 gallons. For ages, Scotch (and some Irish whiskey) distillers have looked to ex-sherry casks to finish their distillates and create some damn fine Scotches: Glendronach 12, Glenfarclas 15, Aberlour 10. Finishing Scotch in sherry casks has become so popular that a cottage industry in Spain has sprung up to cooper these European oak, slender casks; age unmarketable sherry (i.e. low-grade) sherry in them for 3 years; then distill the sherry into Spanish brandy. (For a nice look at why Scotch boomed in the 20th century while Irish whiskey wilted, read on here.)

- Hogshead — 59–66 gallons. Made from ex-bourbon barrels, often repurposed. Used especially in Scotland, coopers make hogsheads by taking apart ex-bourbon barrels and reassembling them into slightly larger casks with new ends. The slightly larger size of the hogshead allows distillers to store more barrels per square foot in their rickhouses. From whence did these porcine vessels derive their name, you may ask? From a 15th century English term “hogges head”, a unit of measurement at the time equivalent to 63 gallons.

- American Standard Barrel — 50–53 gallons. Constructed from new American white oak or (less often) European oak, American Standard Barrels are the go-to cask used by the most well-known bourbon distillers like Four Roses and Heaven Hill. Craft distillers, on the other hand, have found success aging bourbon in the next cask on this list. (Wondering what exactly qualifies as bourbon? We read your mind and wrote about that here.)

- Quarter Cask — 13 gallons. Manufactured to precisely 1/4 the size of an American Standard Barrel, quarter casks provide distillers with a method by which to more quickly age distillates. Quarter casks are the same proportions as American Standard Barrels, but with 1/4 the amount of whiskey in each, the increased surface area of oak to liquid helps age whiskey more quickly. Notable proponents of the Quarter Cask include American craft distilling scion Tuthilltown with their Hudson Baby Bourbon, and esteemed Scotch producer Laphroaig.

- Barracoon — 1 gallon. Roughly the size of the small oak ASW barrels you may have seen in local bars or available for purchase in our shop, the amount of wood in contact with such a small volume of liquid seriously fast-tracks the aging process. Not always optimally, either.

I'm sure all of this has you wondering what types of casks we'll be using. Well, for starters, we'll try a combination of quarter casks and American Standard Barrels. As we build up stocks, we'll move to mostly American Standard Barrels. That said, we'll also roll out some unique finishing methods in the not-so-very-distant future. We'll reveal those later, so be sure to stay connected with us by signing up for our email list or following us on social media.

Cheers!

Weekend roundup: June 17

--Can Ireland Become The Center of the Whiskey World? The Daily Beast weighs in: http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2016/06/11/can-ireland-become-the-center-of-the-whiskey-world.html

--If interested in the above story, try the history of Why Scotch Boomed while Irish Whiskey Wilted, our own well-research writeup on the topic. http://www.aswdistillery.com/crafted-with-characters/why-did-scotch-succeed-while-irish-whiskey-wilted

--Booze and The Bizarre have always found common ground, a trend in no way limited to the US. As the Associated Press reported earlier this week: Ukraine Says Border Guards Found Bootleg Alcohol Pipeline. http://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/ukraine-says-border-guards-found-bootleg-alcohol-pipeline-n587156

--Interested in investing in whiskey. There's a new way to do so, through the first Whiskey-based Exchange Traded Fund. Business Insider on the scoop: http://www.businessinsider.com/whiskey-etf-2016-6

--Nice roundup of the 14 best craft distilled whiskeys under $50, incl. Wasmunds / Copper Fox & Catoctin Creek, from the ever-prescient Eater http://buff.ly/23dO50U

--“New [craft] malteries might use a combination of box-malting and floor-malting techniques” - A Whiskey Wash article on the ascendance of malteries as whiskey has grown by leaps and bounds http://buff.ly/21oiS9P

--“Disarming preconceived notions of what rum is, or ought to be (aside from a sugarcane distillate ), turns out to be a decidedly difficult task: rum, in fact, exists as one of the most conceptually-loaded liquors in all the Seven Seas.” http://www.eater.com/spirits/2016/6/10/11903514/whiskey-scotch-bourbon-rum

--If interested in whether rum can become the next bourbon, in face off the odds described by the Eater article above, check out our send-up of the subject from last week: http://www.aswdistillery.com/crafted-with-characters/is-rum-the-next-bourbon

Why Scotch boomed while Irish whiskey wilted

You may be aware that our double pot still system hearkens back to the traditional Scottish and Irish whisk(e)y* stills, in large part to allow us to experiment with high malt mash bills (recipes). If all goes well, we’ll blaze new trails in whiskey profiles and expand whiskey drinkers’ perceptions along the way. At the same time, we’re firm believers in knowing full well the traditions and distillers to whom we’re indebted.

One of the more interesting questions from the last century in whisk(e)y is why Scotch succeeded, while Irish whiskey — until recently — wilted. Namely, why did Scotland’s top export experience a whisky-driven boom throughout many years of the 20th century, while Ireland’s industry withered down to a paltry 4 distilleries in the 1960s?

You may be aware that our double pot still system hearkens back to the traditional Scottish and Irish whisk(e)y* stills, in large part to allow us to experiment with high malt mash bills (recipes). If all goes well, we’ll blaze new trails in whiskey profiles and expand whiskey drinkers’ perceptions along the way. At the same time, we’re firm believers in knowing full well the traditions and distillers to whom we’re indebted.

A view of our stills

One of the more interesting questions from the last century in whisk(e)y is why Scotch succeeded, while Irish whiskey — until recently — wilted. Namely, why did Scotland’s top export experience a whisky-driven boom throughout many years of the 20th century, while Ireland’s industry withered down to a paltry 4 distilleries in the 1960s?

The question becomes all the more perplexing when reading about the earliest history of whisk(e)y. All but the Scottish appear to agree that the Irish Gaels created the original uisge baugh, whose name was later shortened to “whisky” by the lexically laconic British.

When Aeneas Coffey perfected the column still centuries later in 1834, Scotch whisky makers made the switch in hopes of making whisky for less money. But the whiskies they began producing were of such poor quality that Irish distillers, who had continued using traditional, flavor-retaining pot stills, added an “e” to distinguish their superior product from the inferior “whisky” of Scotland.

Yet despite Irish whiskey’s auspicious beginnings, its serendipity soon sounded a swan song. In 1838, a Catholic priest by the name of Theobald Mathew — which, according to Irish pronunciation, almost certainly rhymed with “Ah-Choo!” — established the Teetotal Abstinence Society. Sixty years later, James Cullen founded Ireland’s Pioneer Total Abstinence Association. The legacy of these temperance movements continues to this day: 20% of Irish adults are teetotalers.

But the challenges had only just begun with 1838’s first temperance movement. Beginning in 1845 and spanning a grueling seven years, the Irish Potato Famine — or the “Great Famine” in Ireland — sent the island’s population plummeting by 20%. One million emigrated to foreign shores and one million perished from starvation and malnourishment. During this time, Ireland lost an estimated 70 distilleries. Still, global consumers regarded the 20 or so remaining distilleries’ whiskey as some of the finest spirits in the world.

The Great Famine kickstarted a chain of events that later proved fatal to most of these remaining distilleries: the Irish bid for independence.

In the Easter Rising of 1916 and the successful Irish War of Independence that began three years later, Ireland attained complete independence from the crown. However, the victory came at the expense of British trade, costing Irish distillers their primary market. In a stroke of genuinely terrible luck, the U.S.’s thirteen-year social experiment (Prohibition) began during the height of the war with Britain, closing off yet another crucial market for Irish whiskey. By the 1930s, even the mighty Old Midleton Distillery produced less than three weeks per year.

World War II sounded the final death knell for Irish whiskey, which went the way that French cognac had only a few decades earlier during the Great French Wine Blight. Irish distilleries, which had scoffed at column stills since their inception, would never regain their footing against Scotch distilleries and their part-column-distilled blends. Today, blended Scotch still accounts for at least 90% of the global Scotch market.

In 1966, three of the handful of remaining Irish distilleries combined to form the Irish Distillers Association in a last-ditch effort to stay viable, a time when Scotch was experiencing a global boom.

Finally, in 1987, Ireland reversed the trend with the advent of Cooley, located on the east coast of Ireland in Dundalk. This marked the beginning of a slow turnaround for the spirit —in fact, last year Irish whiskey was the world’s fastest-growing whiskey segment. But this is more a testament to how far Irish whiskey had fallen than anything else, giving this delicious liquid significant room for growth without coming close to Scotch’s global sales.

A view from Galway, Ireland, one of the main stops on the way to the Connemara Peninsula. Photo courtesy of Jess Hunt-Ralston at Rose & Fig.

Certainly, the divergence between Scotch and Irish whiskey is not entirely due to the (bad) luck of the Irish or Scotch distilleries’ move towards blends. In fact, we’d be most remiss not to mention the friendly “open source” attitude towards whisky in Scotland, where distilleries are willing to trade casks of whisky to create new flavor profiles. This novel approach stands in stark contrast to virtually all major whisk(e)y markets around the world — from Japan to the Bluegrass State.

Scotch distillers’ willingness to trade is somewhat akin to Google and Facebook ascending to dominance by building open-source ecosystems to allow others to expand on their frameworks. In the case of Scotch distilleries, it’s more like “expand on flavor profiles”. It’s really quite brilliant and has led to incredibly tasty blends like Compass Box, in addition to the world-renowned Scotch single malts that win awards year-after-year.

That said, we may see more of this collaborative attitude in Ireland in the years to come, with smaller craft distilleries like Teeling and Dingle Distillery opening recently. (Craft distilleries, like their craft brewing forebears, seem to generally be open to collaboration.) Regardless, we’re excited to see what kind of a comeback the future has in store for Irish whiskey.

— — — —

*When referring to whisk(e)y as a broad category including both Scotch and Irish styles, we use the “(e)” nomenclature to be inclusive of both the Scottish and Irish spellings of the word.

Weekend roundup: June 10

--Given that our stills can, by design, only make whiskey, brandy, and rum, we thought we'd weigh in on whether #rum is the next #bourbon, a question that we've gotten quite a lot recently. http://buff.ly/1PhfPK6

--Long before Jack Fire, we had An Dram Buideach - Vine Pair's primer on the original flavored whisky: Drambuie http://buff.ly/24u8tK7

--Piece on a top-shelf #bourbon of yore, Old Crow. Some of their old barrel racks line our distillery by The Whiskey Wash http://buff.ly/213R3Ds

--The birth, death, and rebirth of tiki bars, by The Daily Beast: http://buff.ly/1PhgD1y

--The Rise of Bourbon: Hotels Are Jumping in Full Barrel, by US News http://buff.ly/1tmG4uv ...We've certainly found this to be the case in Atlanta.

--Want to invest in whiskey? Soon, you'll be able to through a whiskey Exchange Traded Fund. http://www.businessinsider.com/whiskey-etf-2016-6

Is rum the next bourbon? Our thoughts

Before bourbon became bourbon in the 1820s, before the American Revolution began, even before George Washington got his wooden teeth, rum was America’s favorite spirit. (Come to think of it, could rum’s high sugar content have played a part in GW’s wooden grill? He was a fan of Barbados rum, after all.) Given that our stills can, by design, only make whiskey, brandy, and rum, we thought we'd give our thoughts on whether rum is the next bourbon, a question that we've gotten quite a lot recently.

Before bourbon became bourbon in the 1820s, before the American Revolution began, even before George Washington got his wooden teeth, rum was America’s favorite spirit. (Come to think of it, could rum’s high sugar content have played a part in GW’s wooden grill? He was a fan of Barbados rum, after all.) Given that our stills can, by design, only make whiskey, brandy, and rum, we thought we'd weigh in on whether rum is the next bourbon, a question that we've gotten quite a lot recently.

Quality producers

Any spirit that's going to be touted as the next hot thing has to have a bedrock of quality producers - there's a reason moonshine has more or less petered out as a movement. So the first question we must answer in trying to unravel the market-based mystery of whether rum is the next bourbon is this: are there distilleries that produce flavorful, high-quality rum. The answer is a resounding yes. From the U.S.' only single-estate rum a couple hours south of us in Richland Rum, to true mountain rum in Crested Butte's Montanya, we're not staring at a dearth of quality producers.

As a related question, we must next ask whether rum's flavor profile is accessible enough for thirsty consumers across the country and the globe at large to enjoy it on a regular basis.

Rum’s flavor

The cocktail movement has led to a revival in all things rich in history, rum included. Craft cocktails are often sweet, as is bourbon, ice cream, and a number of other American favorites.

From this angle, then, it also seems rum could become the next hot spirit, especially when you consider how different rum flavor profiles can be: some smoky and almost Scotch-like, some unaged and spicy, like Bacardi or an unaged cachaca. Yet this could also hurt rum, as we'll explore a little later.

Whiskey's rise as a model?

Geographic provenance

We’ve seen Japanese whisky rise from relative obscurity to international stardom (and booming sales), bourbon rise from being a date-less prom-goer in the 90s to class president, and the resurgence of Irish whiskey. Thus, you could reasonably theorize the common thread being the centrality of a common geographic region. (Japanese whisky must come from Japan, bourbon must originate in the US, and so forth — lending a certain provenance to each liquid.)

Japanese whisky wasn’t event a thing until 1924, so it’s evidence that a region with a few quality distilleries can establish an entirely new category in a few decades. It’s conceivable to think a few quality rum distilleries in South Carolina or Spain or Sweden could do the same.

Cultural boost

Or you could reasonably assert that whisk(e)y — especially bourbon — has been bolstered by the craft cocktail movement and mixologists across the country embracing the spirit, which has led to a rise in restaurant & bar sales, ergo expanded bourbon sections, ergo more mindshare when people walk into off-premise establishments, ergo higher sales.

You might even say whisk(e)y in general has boomed because of pop culture support. Starting with high-class cocktails in Sex and the City, followed by Old Fashioneds in Mad Men, Jameson shout-outs by Lady Gaga, and untold whiskey references in popular songs all along the way.

The reality is, spirits of all types require a combination of factors to hit escape velocity.

Bourbon is booming right now, vodka had a real moment in the post-World War II years in America, Cognac did it one hundred years prior to that, and even gin did it in mid-1700s Britain (a period known as the “Gin Craze”). So rum might get to enjoy its moment, too.

Rum isn’t there yet and would need more institutional support. From what we’ve seen, barkeeps are starting to embrace rum for more spots on their cocktail menus precisely because it’s less expensive. So who knows — this could possibly be the first in a chain of events leading to the tipping point for rum.

Classic Cocktails

One last thing to mention in rum's favor: it doesn't hurt that some of the most iconic cocktails such as the Daiquiri and the Mojito happen to include rum.

Why rum may not quite become the next bourbon

We would be remiss not to include a few bullets about what may make rum less likely to take off than Japanese whisky, bourbon, and Irish whiskey and the booms they’re all enjoying:

- Currently, the majority of rum distilleries reside in tropical areas where aging occurs much more quickly because of the heat. So it’s very difficult to age a rum for 23 years, or even 5 years for that matter. (Up to 10% is lost per year to evaporation as "angel's share" in the hottest climates.) So if consumers look to age as a defining factor of quality, rum could well struggle. For a little more on why age alone isn’t a great proxy for quality, check out Chad’s analysis here. That said, one of the most lauded whiskies of recent memory, Amrut, comes from equally as hot India, and lacks the age statements that some consumers demand. So not everyone adheres to this imperfect heuristic to assess spirit quality, countering our point.

- The word rum doesn’t have quite the ring of the two-syllable whiskies, cognacs, bourbons, and vodkas of the world. Even Old Tom Gin rolls off the tongue in a sing-song sort of way. It sounds inane, but these things matter. Bourbon is just fun to say.

- Rum’s lack of regulations could impede its progress. Bottles of spirits cost more than six-packs of beer, so consumers are less prone to experiment with craft spirits than with craft beer. One or two bad experiences with pricey rums could be enough to turn people off. As mentioned, rum profiles are all over the place — some rums drink like Scotches, others drink like vodkas. In contrast, even if a drinker doesn’t like a particular bourbon, they will rarely be entirely thrown off by the liquid, since regulations require 51%+ corn and a host of other things. So they’re unlikely to write off the entire category because they drank something they weren’t expecting.

- Classic cocktails not as famous as bourbon's. Despite the classic cocktails mentioned above, rum's most notable cocktails don't seem to have received as much cultural cachet as bourbon's in the form of the Manhattan, the Old Fashioned, and the Mint Julep. A show may come along that touts the cool factor of, for example, the Planter's Punch, the way that Mad Men bolstered the Old Fashioned. But we haven't seen one yet.

Our final thoughts

Personally, we’re cheering for rum because (A) it’s delicious, (B) Georgia has a couple awesome rum distilleries already (Richland and IDC), and (C) our own twin copper pot stills can make whiskey, brandy, and rum, so we wouldn’t mind getting to learn how to make another spirit.

Whether rum becomes as big of a spirits category in the market is up for much debate. But then again, a spirit doesn't have to enjoy a $3 billion market share like bourbon to be enjoyable. Craft distilleries across the country have made rum for a long while and will continue to do so, because it's damn delicious and other people seem to think the same.

Weekend roundup: June 3

--A Forbes article on the scientific evidence supporting the notion that women are better whiskey-tasters than men: http://buff.ly/1THx0X8

--An in-depth piece on how frontier settlers made #whiskey before #bourbon was a thing. http://buff.ly/1XK1HzO

--Nice peek at The Next Frontier of Whiskies Inspired by Beer, including mention of one of the American single malt pioneers, Westland Distillery out of Seattle http://buff.ly/1PdvjnO

--Interesting Quartz look at Park City, Utah's High West and how they're trying to engrain a blending culture similar to Scotland's into the fabric of US whiskey culture. http://buff.ly/1PqPEWA

--An enlightening glance at the earliest history of #Scotch by UK's @Telegraph http://buff.ly/1TNe5Ko

So what exactly makes bourbon, bourbon?

As we close in on the date we run our first bourbon through the stills, we thought it would be worthwhile to explore what exactly bourbon is, because lore and truth about our official spirit seem to have diverged in the snowy woods of time. With your permission, we’ll take the less-traveled road of truth on this one.

As we close in on the date we run our first bourbon through the stills, we thought it would be worthwhile to explore what exactly bourbon is, because lore and truth about our official spirit seem to have diverged in the snowy woods of time. With your permission, we’ll take the less-traveled road of truth on this one.

Made in the US

First things first, bourbon must be made in the US. That’s where the lawmakers have drawn the line. So does bourbon have to be made in Kentucky? No. That’s just what they’d like you to think. Rather, any distillery in the US — even that youngster, Hawaii (our 50th state), over two thousand miles off the California coast — can make bourbon.

And a number of non-Kentucky distilleries are making delicious ones, at that. Don’t believe us? Book a direct flight to Austin, Texas, then saddle up a vehicle and drive an hour due west to find out first hand at Garrison Brothers Distillery.

At least 51% corn

Next up, bourbon’s grain recipe must consist of at least 51% corn. This makes sense, as bourbon first originated around 1820 in the South, where corn grows with reckless abandon. The rest of bourbon’s grain recipe (the “mash bill” or “grain bill”) may consist of any other grain. Rye, barley, and wheat arethe most common. Note that there are two main styles of bourbon today: high rye and high wheat. The difference boils down to the secondary grain.

After corn, if a bourbon’s next most prominent grain is rye, it is, not surprisingly, considered a high rye bourbon. These are spicier and bolder. Examples include Four Roses, Jim Beam, and Bulleit (which was, until recently, made by Four Roses).

If a bourbon’s next most prominent grain after corn is wheat, it’s a high wheat bourbon. These are more rare and often have notes of salted caramel. Pappy Van Winkle, Maker’s Mark, and our first bourbon, Fiddler, all fall into this category.

Aged in new charred American oak

Third, bourbon must be aged in new charred American oak, most often in the form of a barrel. Note here that, though most people refer to all beer-belly-shaped vessels for aging whiskey as "barrels", “cask” is the more correct term in the industry. Why? Because “barrel” refers only to standard 53 gallon casks that most bourbon today is aged in, while some distilleries use 30 gallon or 15 gallon barrels/casks, known as “quarter casks”, or even casks that are bigger than the standard 53 gallon bourbon barrel if they so choose. (Although it wouldn’t be ideal, as bigger casks take more time to age whiskey.) Learn more about the various types of casks, including the American Standard Barrels oft-used for bourbon here.

Also notice that there’s no requirement for a minimum time spent in new charred American oak. So as soon as “white dog” — or newly made bourbon —touches the inside of a new, charred American oak cask, a distillery can call it a bourbon. But a mere week inside a cask often isn’t enough time to smooth out the otherwise rough-hewn new make. This is why most bourbon is aged at least one year. It’s not required, but palates the world over strongly encourage it.

One final thought on the charred barrels: by charring the inside, a cooper caramelizes parts of the oak known as the hemicellulose, lending flavors of chocolate and butterscotch, and lignins, lending vanilla characteristics. The charred interior also acts as a charcoal filter to shake the spirit down for all its hard edges as it passes in and out of the oak’s pores over the months.

The final two requirements for bourbon are a bit nerdier and more technical — both are requirements of proof, or alcohol by volume.

Distilled at no higher than 160 proof

To qualify as bourbon, the 51%+ corn spirit cannot be distilled higher than 160 proof, or 80% alcohol by volume. Why is this? Because Congress determined that, above 160 proof, a spirit starts to lose the bold and spicy characteristics that define a typical bourbon, becoming less distinctive in the process.

Put into barrels at no higher than 125 proof

The other proof requirement and final overall requirement stipulates that new make that would otherwise qualify as bourbon cannot enter a barrel at more than 125 proof. Why is this? Well, there you stumped us. But conjecture has always been a favorite pastime of ours. So we’ll speculate that a first-term Congressman from Missouri had, through the years, witnessed firsthand what slack demand can do for entire industries and decided to do something about during in the early 1900s.

Weekend roundup: May 27

--In case you missed it, we posted an in-depth look at Islay earlier this week. http://www.aswdistillery.com/crafted-with-characters/an-americans-notes-on-islay-and-its-peaty-scotch

--Check out some of the US' awesome new craft distilleries, including Long Road Distillery in Michigan Waterford Distillery, among others, in a great roundup by Time Out Magazine http://buff.ly/1NH32Wj

--Is High-End Rum the New Whiskey? Forbes weighs in: http://buff.ly/1WNfSWe

--Interesting new release of a Hangar 1 vodka made with San Francisco fog. Gimmicky? Maybe. But it does help promote a most laudable cause in FogQuest, which helps folks in rural, developing parts of the world to harvest fog as an option for potable water: http://marketwatchmag.com/hangar-1-fog-point-vodka/

--Modern-day alchemy: the emerging art of US craft distillers turning craft beer into whiskey: http://www.eater.com/drinks/2016/5/18/11693112/beer-whiskey-craft-pa-wheat-ale-arcane (Note, German distillers have been doing this for ages, so it's not exactly new.)

--What happened to the 400 illicit producers of moonshine in Scotland? An interesting read from VinePair on the emergence of the licensed distillery in the birthplace of uisge beathe. http://vinepair.com/wine-blog/how-lowering-taxes-killed-the-scotch-moonshining-industry/

--

Chad Ralston, CSS ASW Distillery (678) 592-5103 aswdistillery.com

A deep dive on Islay and its peaty Scotch

The sunrise splintered the drapes of our room at the Bowmore House B&B just after 6am. The blue that you only find on rural drives and remote islands stretched taut across the horizon. The breeze came in bursts off the Atlantic, still laced with hints of ice on this early May day. My wife and I had finally made it to the crowning jewel of our much-delayed honeymoon: a three-day journey into the heart of Islay and its bounty of whisky bliss. Some biased observers might call it the best honeymoon ever. I fall firmly into this camp.

The sunrise splintered the drapes of our room at the Bowmore House B&B just after 6am. The blue that you only find on rural drives and remote islands stretched taut across the horizon. The breeze came in bursts off the Atlantic, still laced with hints of ice on this early May day. My wife and I had finally made it to the crowning jewel of our much-delayed honeymoon: a three-day journey into the heart of Islay and its bounty of whisky bliss. Some biased observers might call it the best honeymoon ever. I fall firmly into this camp.

As Israel was the fulcrum of the Fertile Crescent for agriculture 4,000 years ago, modern-day Islay is the Phenol Crescent for modern-day whisky. The vast majority of its distilleries produce some of the world’s peatiest Scotches, clocking in at 15–300 parts per million in phenols. (In contrast, The Macallan — what some would consider a moderately smoky Scotch — has 1.5 phenol parts per million.)

To venture into the depths of one of these distilleries is to walk through history — living, breathing halls that have produced some of the world’s best whisky for centuries. Even before I stepped off the ferry at Islay’s Port Ellen — itself a now-shuttered distillery of legend, bottles fetching thousands of dollars — I rated a number of Islay’s whiskies as many of my favorite drams of all time.

The more modern of the two ferries to Islay. Apparently, the other one has an impeccable track-record at inducing seasickness.

In homage to the annual Islay Festival of Music and Malt, which throws down in late May and early June every year (and runs through Saturday this year), we’ve put together a primer on each of Islay’s eight operating distilleries as of May 2016.

Although I’m not a distiller, I consider myself a whiskey-man, especially under the tutelage of our resident distillation encyclopedia and head distiller, Justin Manglitz. So many of my thoughts below relate to the art of distilling, in addition to the whisky and tasting room experiences you’ll find there and more general musings on Islay and its ineffable scenery. (Scenery that my uber-talented spouse, Jess Hunt-Ralston, photographed to perfection throughout this piece. Check her other work out at roseandfig.com.)

(And many thanks to our knowledgeable guide Stephen from Scottish Routes, who shared stories ranging from the Goliath-sized William Wallace to the escape artist wombats of Loch Lomond.)

Lagavulin ("log-uh-voo-lin")

One of the “Big 3” of Islay, Lagavulin’s pagoda-capped, white-washed warehouse announces itself from the shore as you ferry into Port Ellen. Affiliated with beverage multinational company Diageo, the distillery consistently produces drams that win gold medals the world over.

We arrived for the Lagavulin Warehouse Experience around 10am and followed the self-described “mound-shaped” tour guide Iain past the tastefully festooned, Lagavulin-green gift shop into the distillery’s cool, damp rickhouse. As we nestled in amongst thousands of repurposed bourbon barrels and rhinoceros-sized sherry butts, Iain got to work appointing volunteers to draw whisky directly from Lagavulin’s casks into a large beaker.

As we enjoyed the cask-strength (55%+ alcohol by volume) Jazzfest, 12-year sherry cask, 14 year, 18 year, 23 year, and 34 year, Iain poked fun at the lot of the 50 or so people attentively awaiting his next move. He reserved the comment “what, are ye writing a magazine article?” for me, pointing to the notebook I carry with me to jot down tasting notes. He selected numerous eager tipplers from the crowd to wield the copper valinch the size of a sword and withdraw a large beaker’s worth of whisky from each cask. (A valinch is known as a whiskey thief in the US.)

In between bouts of shaking the whisky — for aeration, one supposes, although some was leaking onto the floor — he asked us why we thought each cask loses approximately 3% of its whisky each year. One bold Dane suggested, “because you’re shaking it so much.” Iain grinned puckishly and told us that the 3% per year cut is the angel’s share, the environment’s price of admission through evaporation.

As we sniffed, sampled, and salivated our way through the briny, bittersweet whisky, I settled on the 12 year sherry cask finish and 18 year expressions as my favorites. In particular, the 18 year was white-gold, suggesting perhaps a third-use cask (the last use before being retired to some green thumb’s rose garden). The nose was somehow robust and delicate at once, a duality of dram evincing rose water, lilac, charred butter, green banana. The palate was even bolder, with pecan pie, dark chocolate, coffee, blackberry, bitter orange, saffron, sage, roast chicken with thyme, and something akin to honeyed porridge. (Not to be confused with honey-eyed porridge, which is the mythical dog of the Quaker Oats farmer.)

As we concluded the tasting, Iain suggested that a small group of us take photos on Lagavulin’s pier. With the sun bursting against the whitewashed wall of their warehouse and a band of enlivened Norwegians to each side, Iain grinned toothily and said, “Smile. Laphroaig!”

Those two words summed up the lively, instructive experience at Lagavulin. All in all, Lagavulin proved to be Jess’s favorite distillery experience on the island.

Soon, our tour bus whisked us off to the Kildalton Church for some much-needed sanctity and sobriety. An unattended Igloo ice chest with cakes, coffee, tea, and a donation basket greeted us like manna from the flawless heavens that are Islay's skies.

A few photos and some grave perusings later, we jostled down the road to Ardbeg for lunch and an early afternoon tasting.

Ardbeg ("ard-beg")

Ardbeg is, along with Laphroaig, Islay’s second-oldest distillery. But unlike its old kin Bowmore and Laphroaig, Ardbeg has not continuously operated since its 1815 founding (save for Bowmore's voluntary abeyance during the World Wars). At its peak, 200 people lived at Ardbeg, with the distillery at the town center. But the late 1970s & early 80s brought with them lean years in the whisky world, causing Ardbeg to shut its doors in 1981.

Fortunately, it later revived became associated with its next-dram-down neighbor Laphroaig before pairing with Glenmorangie. The group who owned Glenmorangie and Ardbeg later sold the distilleries as a package deal to Moet-Hennessy in 2005.

Ardbeg hasn’t changed much since its early days. They continue to produce some of the peatiest Scotches on the market, with their standard grain clocking in at 55 parts per million phenols. After pitching their dry distiller’s yeast (vs. the liquid yeast that Lagavulin uses), the mash spends 55 hours fermenting in washbacks of Douglas fir and Oregon pine. After this relatively short fermentation period, they pipe the 9% alcohol “distiller’s beer” to their wash stills - the only ones in Islay fitted with purifiers, which are metal tubes resembling old catalytic converters. The purifiers recirculate the heavier elements of the wash run back through the still before moving to the low wines tank. This allows them to inject cold water into tubes before the vapor reaches the wash still’s condenser, helping refine the spirit.(1)

Finally, the low wines travel through Ardbeg's spirits stills. Perhaps because of the purifying process during their wash run, they make a very quick foreshots cut (lasting only about 10 minutes) before sending the 72% alcohol by volume spirit into spirit tanks, ready for casks.

The resulting distillate reminds me a bit of peat-infused bourbon, with lots of cherry. Although pricey, the Corryvreckan is really well done. For those looking for something not quite as expensive, their Uigedail expression refers to one of their two water sources, and translates from Scottish Gaelic as “a dark, mysterious place”.

Laphroaig ("la-froig")

Bias alert: Laphroaig 10 has been one of my house whiskies for quite some time now. Not to mention, their 18 and 24 year expressions — quite difficult to find these days — rank among some of the most storied releases of all time. (Okay, maybe the 18 year isn’t that difficult to find.) So ending our first day here was like a child being permitted to visit Santa’s factory in rural China, er, the North Pole. We pulled into the parking lot of the last of the Port Ellen-side distilleries and stumbled with much coordination off the bus into that glimmering enemy of the besotted eyes, the unbridled Atlantic sun.

Knowing full well that we’d already been on in-depth tours of Ardbeg and Deanston in the Highlands, our guide at Laphroaig concentrated on showing us what differentiates their process. So off we went to the floor malting warehouse, where members of Laphroaig’s team rake damp barley back and forth across a floor until the barley germinates, releasing a number of enzymes vital to yeast during the fermentation process. Unlike Dante’s Inferno and Waiting for Godot, the back-and-forth motions yield not more misery and bewailed musings, but rather delicious malt, ready for moderate smoking from some of the peat Laphroaig harvests just around the bay from Port Ellen, near the Islay international airport’s lone runway. (They make approximately 20% of their malt in-house.)

A nugget of Laphroaig's peat.

After the entertaining tour, they led us to the warehouse for a quick peek at their casks before guiding us to the promised land, the tasting room. As Islay mandates that distilleries stop serving at 5pm, presumably so inebriated patrons can drive back to their hotels by the guiding light of dusk, my wife hustled to the Friends of Laphroaig kiosk. She returned with title — no doubt, in fee simple — to two 4-square-inch plots of land in a once-disputed field across the road from the distillery. Laphroaig may or may not have instituted the Friends of Laphroaig program as a response to the dispute.

We then sampled Laphroaig’s Three Wood and 15 Year expressions. Delicious, to say the least, my wife bought a bottle of the Three Wood to savor its coconut, orange marmalade, graham cracker, and chocolate notes upon returning stateside. I sprang for the 15 Year expression, as it doesn't grace the shelves of Atlanta's bottle shops. And, of course, we packed our 50ml bottles of Laphroaig 10 that we received in addition to our eminently buildable 4 square inch plots.

Bowmore ("buh-mohr")

Bowmore is Islay’s oldest distillery, dating to 1779 when a local by the name of John Simson opened its doors, before conveying it to the Mutters a few years later. (James Mutter was Vice Consul of the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, and Brazil through their Glasgow consulates.) In 1925, the German-descended Mutter family sold the distillery to J.B. Sheriff & Co. During World War II, Bowmore stopped production to accommodate the RAF Coast Command’s anti-submarine campaign headquarters.

Currently, Bowmore sources barley from both Islay and the mainland, and still conducts a portion of its own floor maltings. A former Bowmore warehouse encloses a public swimming pool heated by waste heat from the distillation process.

Alas, time did not prove accommodative during our visit — The Bowmore B&B where we stayed refers to the village rather than the distillery. I’ve always enjoyed Bowmore’s expressions (if you haven’t tasted their 18 Year, make haste to your nearest whisky bar) and regret not carving out the time the second morning we were there for a quick visit. But that would have required risking mental acuity for my favorite distillery, Bruichladdich. So I guess it means a return visit is in order.

Bruichladdich ("brook-laddy")

Long before I ever knew about Bruichladdich, when I was still studying for various degrees that I have since abandoned in favor of gainful employ in the world of whiskey, I dedicated my glass to gin. Of all the gins, Botanist had staked a claim to my palate more perpetual, more total than any little Laphroaig plot of land in fee simple for all posterity. These were the days when the bottle was the shape and size of a Bible, the gin’s 22 Islay botanicals residing demurely at the bottom of the label.

Occasionally, when I drink, I like to revisit the literature on the bottle whose contents I’m consuming. (I can assure you this is not a thing that happens when I drink alone.) One humid Saturday last June, both gin and tonic mysteriously appeared in my glass, and my old square bottle of Botanist in my hand. Naturally, I read the label and discovered, to my amazement, the same distillery that made my favorite price-accessible Scotch, Islay Barley, also made Botanist. So began an appreciation with the Bruichladdich Distillery that many unbiased observers might mislabel an “infatuation”.

Built in 1881 on the shores of western Islay’s Loch Lindall by the brothers Harvey, heirs to an Islay whisky dynasty, Bruichladdich met the same fate as Ardbeg in 1994, at the height of the El Dorado days of vodka. (If we were into puns, we might even jest the Road to El Dovodo. Fortunately, we’re not into puns.) In the late 90s, an avid cyclist and whisky enthusiast found the mothballed distillery during a rainy ride and put together a bid for the facility. For a number of years, White McKay rebuffed his advances until finally, at the turn of the new Millennium, they let go of their inactive asset for around 6.5 million pounds.

The cyclist, Mark Reynier, and master distiller, Jim McEwan, who’d worked his way up at Bowmore around the bay since the age of 15, pushed Scotch in all kinds of new and exciting directions. From focusing on the terroir of Islay through such releases as Botanist using 22 island botanicals, such as gorse, a thorny bush of yellow, coconut-scented flowers, to experimenting with finishes like red wine casks and the most aggressively peated Scotches in the world, Bruichladdich lived up to its motto: Progressive Hebridean Distillers. (In Scottish Gaelic, "Bruichladdich" means "rocky beach" or "purply beach".)

Twelve years later, Mr. Reynier and company sold Bruichladdich to Remy-Cointreau for a tidy 58 million pounds. For you math-literate and finance-geek types, that’s a return of over 66% per year in simple interest. The distillery now employs 72 people, a remarkable feat for a distillery that wasn’t even operational 16 years ago. Some time in the near future, they also plan to reintroduce the floor maltings that went by the wayside in the 60s. From my completely doe-eyed and myopic vantage, the quality has not suffered post-merger - the influx of funds has just meant a bigger budget to tell the world about their delicious whisky.

With a bigger budget comes the ability to afford bolder Pantone colors.

And the tour matches the quality. We enjoyed the morning stroll past vintage photos of their team, sampled the hefeweizen-esque distiller’s beer from their Oregon pine washbacks, and marveled at their legitimately ancient stills. In addition to their fairly standard-looking wash and spirit stills, they also showed us “Ugly Betty”, one of the last remaining Lomond stills, where all the world’s Botanist supplies are made in the span of only a couple of months every year.

The tour concludes in, where else, the tasting room, where you can buy rare extra-aged expressions, sample many more common expressions, and fill your own 500ml bottle from one of their two cask-strength Valinch series whiskies. These are one-off experiments only available at Bruichladdich that one drinker might describe as “utterly delicious”, while another, more hyperbolic sot might describe as “life-changing”. This go-round, my wife brought home the 10 year, heavily peated rioja finish Port Charlotte (yes, that Port Charlotte of lore).

Meanwhile, I opted for the 26 year, unpeated bourbon finish Classic Laddie. All in all, my favorite distillery experience on the island.

Kilchoman ("kil-who-men")

Islay’s newest distillery is also its smallest. While Islay is best-described as “rural”, Kilchoman is better-suited for the word “remote” — both miles from any town or other distillery and, unlike the equally-as-remote Bunnahabhain, stranded inland. To get there, our vehicle hunkered and jumped past rubber-necking sheep on the peat-cratered road.

The story goes that, after World War II, the family that owned the site on which Kilchoman resides were in the hunt for a vehicle that could navigate the island’s peaks and troughs better than cars of the day. After searching high and low, their search came up dry, so they took matters into their own hands, welding a cabin onto a sedan of sorts. The result was something that looked strikingly similar to the early Land Rover prototypes. Whether Land Rover lifted the idea from this Islay family is a matter of conjecture, but at the least, you can see how an Islay resident might conceive of the idea.

Like Lagavulin, Kilchoman has opted for the traditional pagoda-style turrets that maximize the air flow to the malt kilns. If Kilchoman bought all its malt from Diageo’s Port Ellen malthouse on the island, Kilchoman, which began in 2005, wouldn’t have needed such technology. But, true to its motto as “Islay’s Farm Distillery”, Kilchoman not only malts a large portion of its barley onsite, but also grows the same barley in the surrounding fields.

Its single 4000 liter wash still and correspondingly smaller spirit still make Kilchoman significantly smaller than many of the island’s distilleries. (By at least a factor of five if our math is correct.) But if you’ve ever had a dram of their flagship, Machir Bay (or "fertile landscape bay", in Gaelic), with the beautiful cornflower blue label, you know that what Kilchoman lacks in quantity, it more than makes up for in quality. Perhaps it has something to do with their ex-Buffalo Trace casks.

The tour guide was probably the most personable of any guide we met on the trip. (All the guides were entertaining in their own right.) At only eleven years old, Kilchoman’s stills are much newer than most stills on the island, and also contain the only reflux bubble I saw at any of the distilleries. (We at ASW Distillery have a similar reflux bubble here, 3rd photo.)

This can help provide more precise control over the final distillate. By applying lower heat for longer, the distiller can induce the spirit to condense on the sides of the relatively cooler reflux bubble and drop back into the kettle of the still more times before rising into the condenser. The result is a spirit that has undergone more “mini-distillations” before passing to the next stage of production.

Unlike the other tours, which ended after a look at the stills, Kilchoman led us to their bottling line to see us just how manual and hand-crafted their operation is.

Finally, they ushered us into their private tasting room for a tasting of Machir Bay, Loch Gorn, and 100% Islay. As delicious as the last two were, the Machir Bay still captivated me the most with its notes of coconut and pound cake. As an independent distillery farther along in their whisky journey, we hope y'all give them a look next time you're in the hunt for something new.

Caol Ila ("cool-eela")

Not far from Islay’s world-renowned and Hollywood-enamored Woollen Mill where two of the world’s six operational Spinning Jennys clank out garments day after day sits Islay’s largest distillery and smallest tasting room: Caol Ila. Perhaps best known for supplying a large portion of the whisky that tumbles into Johnnie Walker bottles, Caol Ila has a small but dedicated following.

One of the world's last functioning Spinning Jennys.

Our trip included two such loyalists, Norwegians who, while sipping whisky one damp Wednesday evening with members of their Dram Club back in Norway, had found Caol Ila 18 to qualify for their highest echelon of whiskies.

The narrow road to the distillery winds its way across Islay’s wind-swept fields before a final descent down a road perhaps better meant for pack mules than charter buses or Mercedes vans. Not a quarter mile across the Sound of Islay, a strait with one of the world’s strongest currents, the rocky mound of Jura rises like a breaching mastodon, beads of skittish deer dripping down its back.

This proved to be our shortest visit, as our guide Stephen had a promise to keep with the Bunnahabhain staff, who apparently prefer punctuality to the opposite. The tasting room barely fit our group of 16, but the staff was friendly as they poured us whisky. We sampled two drams, including Moch — both of which seemed a bit one-dimensional to my palate — before posing for a photo with our backs to Jura and the swift strait separating the two islands. As an interesting aside, in 2011, the government hoped to capitalize on the strait’s power by giving the green light for an innovative tidal turbine green-energy project on the ocean bottom.

For Caol Ila enthusiasts, this will be a welcome stop, although for the uninitiated who lacks that most precious resource, time, I would encourage forgoing it in favor of Bunnahabhain just a few minutes to the north.

Bunnahabhain ("boon-uh-hahvin")

The northernmost distillery on Islay, Bunnahabhain lies a few clicks north of Caol Ila. As you arrive, the slate gray tides slushing against polished ocean stones sounds like a distracted daydreamer sweeping a porch. Across the Sound stand the Paps of Jura, a somewhat oxymoronic name given to the two barren slopes prominent on that end of the island.

A fine distillery in its own right, Bunnahabhain is perhaps best known as the “unpeated Islay whisky”. Affiliated with the Deanston Distillery in the Highlands, their flagship 12 Year and delicious 18 Year both fall into this unpeated category, which you can sample up a flight of stairs, past a mounted bell formerly used to announce allotted-dram time.

Before heading to the gift shop, it’s worth checking out their version of the Distillery Experience, nestled in the back of an Amontilladan-like catacomb of their warehouse. The distillery braces you against the cold of the catacomb by furnishing complimentary blankets on the pews surrounding the selected casks on display. In lieu of a jaunt through the rest of the distillery, our tour guide brought us to this dunnage lounge straightaway and talked about the history of the distillery and its whisky.

Both effervescent and knowledgeable, our guide spoke to the distillery’s annual production (around 1.3 million liters per year) and its capacity (closer to 2 million liters per year). Apparently, the demand for Dewar’s, where the casks that don’t make the cut for Bunnahabhain’s own bottlings end up, is not what it once was. (Down 5% in 2015.)

After a sampling of a sherry-influenced expression straight from the sherry butt they had finished the whisky in, we walked back to the tasting room for our final organized tasting of the trip. The 12 Year was a solid expression, brown sugar and jam on the palate, while the 18 Year really shined, melting on the tongue like a warm salted caramel. Fitting, given Bunnahabhain’s location next to the ocean.

Before departing, our group pooled resources to buy Stephen, our wonderful tour guide, a bottle of Bunnahabhain Toiteach. As much as he’d spoken highly of Lagavulin, Laphroaig 18, and Bowmore, throughout the trip, he’d been raving the most about Bunnahabhain. We figured the least we could do would be to give him a bottle he wouldn’t be permitted to consume any time soon. (Duty calls, after all.) He graciously accepted the bottle and took it home to enjoy with his niece, no doubt.

What's next ("watts-neckst")

If you like the taste of Scotch, or enjoy spending time with those who do, Islay is a must-visit. Don't let its remote location deter you. It's only a half-day's drive from the international airport in Scotland's largest city, Glasgow - and half that time is spent on a truly inspirational ferry ride past rocky atolls and uninhabited islands. The weather in spring alternates between brilliant sunshine and hovering mists, but the temperature doesn't dip much below approximately 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Certainly not a place to soak up the rays on a beach, but pretty much the ultimate place to soak up the rays of the liquid sunshine in your glass. GO. And make haste. You aren't getting any younger.

(Fortunately, neither is the whisky. Unless you've become despondent about age statements disappearing from bottles. Which, historically, is quite precedented, as age statements only appeared with consistency fairly recently as companies figured out ways to market their stocks of long-aged whisky. But that's for another entry entirely. Until then, Cheers and Slainte!)

----------

(1) In the US, a purifier is known as a dephlegmator and is more often associated with the column stills used in large-scale bourbon distilleries, rather than the pot stills of small-batch makers. Current President of the American Distiller’s Institute, Bill Owens, in his book The Art of Distilling Whiskey, Moonshine, and Other Spirits, describes it thus: “The dephlegmator resides above the top bubble-cap tray. It is a chamber at the top of the column with numerous vertical tubes for the vapor to travel through on its way to the condenser. There is a water jacket around the vertical tubes that the operator can flood with cooling water to increase the amount of reflux [volume of spirit that recirculates through the still for further refinement]. The water level in the dephlegmator can be adjusted to give granular control over the amount of reflux.”

Weekend roundup: May 20

A really interesting week in whiskey. Here's a weekend roundup for you to enjoy over a nice dram:

--“It's that complexity that is at the heart of calvados.” Great primer on France's apple brandy of legend, Calvados. We'll make something similar whenever we can get our hands on some dry, Georgia apple cider. http://buff.ly/1WnVg6H

--Looking for a good read on one of US craft whiskey's leaders? Check out this piece on High West Distillery. Fun fact: We've heard High West founder David Perkins hails from Atlanta's Virginia Highland region.

--A NYT review of 20 single malts from everywhere but Scotland. Clocking in at No. 3, Hakushu 12, Chad's favorite widely available single malt. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/18/dining/single-malt-whiskey-review.html?_r=0

--Gluten Free Whiskey - Is It Real? The short answer is yes, with some caveats. http://buff.ly/1snypuS.

--How the body metabolizes alcohol, as discussed by an engineer at Google. https://www.quora.com/What-is-considered-having-a-high-tolerance-to-alcohol/answer/Matthew-Lai-17?srid=8jTW&share=1de3e8a6

--An interesting take on whether applejack (apple brandy) is poised to see a renaissance. We've been hearing this speculation for a while now, but it's always interesting to hear an insider's perspective. http://www.craveonline.com/culture/982961-applejack-new-whiskey

--A piece on infrared-charred casks - a process different than the standard method for charring barrels that produces whiskey "slightly ahead of normal cycling and slightly more woody character." http://www.popsci.com/using-infrared-radiation-to-fine-tune-taste-whiskey

Cheers to the weekend!

What makes American Spirit Whiskey clear anyways?

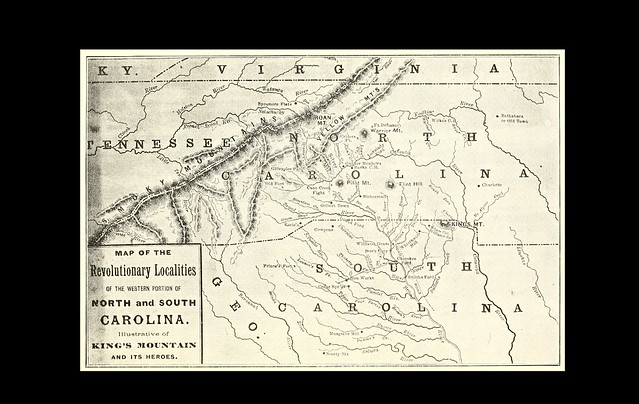

In the late 19th and early 20th century, a tinny-voiced man roughly the height of a chest of drawers dominated the moonshining scene of western North Carolina. Of Irish descent, his grandfather had fought in the Battle of King’s Mountain during the Revolution, a skirmish that President Theodore Roosevelt later described as the “turning point of the American Revolution”.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, a tinny-voiced man roughly the height of a chest of drawers dominated the moonshining scene of western North Carolina. Of Irish descent, his grandfather had fought in the Battle of King’s Mountain during the Revolution, a skirmish that President Theodore Roosevelt later described as the “turning point of the American Revolution”.

Out of necessity in the hardscrabble years leading up to the Civil War, Owens forewent formal schooling and, by age 14, had hired himself out as a “drawer of water and hewer of trees”. By the age of 23, his water-drawing skills had supplied him with enough money to buy 100 acres on Cherry Mountain, not far from Asheville, North Carolina.

Around that time, he transitioned from drawing water to distilling it, paying the justice of the peace who witnessed his marriage’s vows in brandy made from the cherry trees that grew abundantly on the slopes of Cherry Mountain. At its peak, the brandy-and-spice “cherry bounce” that Owens produced on his Cherry Mountain estate was served as far west as the Mississippi River.(1)

In Owen’s day —a period spanning from the era before Lincoln all the way through the first Ford motor vehicles — much of the spirits served were clear spirits. But the spirits enjoyed in his day and age were not the gin and vodka that came to dominate Prohibition and the post-War era. The spirits were whiskey and brandy, two spirituous elixirs normally associated with sepia tones.

Turns out that all spirits — whether gin, vodka, rum, or whiskey — leave a still as clear as a mountain creek or a conscience after bathing in one. It’s time in a barrel that gives most whiskey its brown hue — mainly from processes known as oxidation and extraction.

But if most whiskey is brown, why did we choose to roll out a clear whiskey as our first product? (Or “silver whiskey”, as some call it, similar to silver tequila.) As startups, craft distilleries have to concern themselves with cash flow, and often, the lack thereof. Socking away 100 barrels of bourbon for bottling in 4 years is all well and good, but in the meantime, you’ve got to figure out a way to keep the lights on.

That’s why so many craft distilleries of today bring a vodka or a gin to market first. Neither has to spend any time in a barrel, so a distillery can go from sacks of grain to filling glass bottles in less than a week. Compare that with the 12+ months needed to create a tasty bourbon — often much longer.

Not to mention, starting with vodka or gin means starting with a well-known category that doesn’t suffer from category-creation issues. So instead of having to educate thirsty drinkers on what exactly your product is, you can focus on what exactly differentiates your product from others on the market.

All of this adds up to a tried-and-true recipe for many startup distilleries, a wise move to ensure the lights stay on long enough to unveil the straight rye or sugarcane rum they’ve been aging all along.

We’ve always abided by the adage Do What you Love. You can truly tell the craft distillers who love gin from the care that goes into crafting their end-products. (St. George Botanivore, anyone?) At the same time, when we first created American Spirit Whiskey, we didn’t love vodka, or gin (we’ve since changed our minds on gin).

We did, however, love whiskey. We’d become well-acquainted with it since our days at the University of Georgia. We’d combed the City of Atlanta for our favorite bottles as they disappeared during the whiskey craze. We’d talked about the world at large while sipping it late into the evening.

So we decided that an unaged whiskey is where we’d devote our efforts. We knew the odds were against us — that we faced the category creation issues that have shut down concepts as wide-ranging as the Segway and the Sony MiniDisc. That we’d have to spend much of our days educating folks not just on what American Spirit Whiskey tasted like, but on how it was made, why you should try it, and, once a damn-that’s-good grin crossed their lips, what you could do with it. But adversity has never much deterred us, and so onward we marched.